All the early COVID-19 stories censored off Chinese internet

Illustration by Derek Zheng

The first few weeks after the novel coronavirus appeared in Wuhan saw China’s beleaguered domestic media rise to the occasion. Through brave reporting, Chinese journalists highlighted whistleblowers and government malfeasance, showing that they can still do amazing work. But while there was a short period marked by a relatively freer media environment, censorship did not completely abate.

The article translated below, which first appeared in Young Weekly, examined 20 of the most popular and influential media accounts in the WeChat Official Account ecosystem and analyzed which of their reports were deleted. It found that business media, negative reporting, and articles focusing on doctors and patients got the most attention from censors.

In an attempt to evade WeChat’s censorship algorithm, the article blurred some characters, sprinkled in English words, and threw in dashes of pinyin. It racked up tens of thousands of views before disappearing a few hours after publication.

Young Weekly is produced by nine graduates from Nanjing Normal University’s journalism class of 2017. Most of the censored articles highlighted below can be found on Github’s nCovMemory site.

The 41 Disappeared Coronavirus Articles

消失的41篇疫情报道 (xiāoshī de 41 piān yìqíng bàodào)

Young Weekly. The original article is archived here. March 23. Translated by Jordan Schneider, with help from Erik Stahle.

The news is history’s first draft. In the time of COVID-19, a constant stream of about 700 journalists went to Hubei to report from the front lines. Understandably, the demand for news had grown a ton.

In this time, the viewership of TV programs like Common Concern (共同关注 gòngtóng guānzhù), Oriental Horizon (东方时空 dōngfāng shíkōng), and News 1+1 (xīnwén 1+1) exploded, while news magazines like Cáixīn 财新, Sanlian Life Weekly (三联生活周刊 sānlián shēnghuó zhōukān), and People (人物 rénwù) sold out completely. Due to this popularity, some magazines even implemented rarely seen advance sales.

On the internet, article after article flooded everyone’s Wechat Moments. This explosive news coverage truly resonated with the public. Amid all this noise, a few articles disappeared very quickly, and as such, disappeared from public discussion.

According to Young Weekly’s incomplete statistics, as the epidemic was getting worse, Freezing Point Weekly (冰点周刊 bīngdiǎn zhōukān), Caijing Magazine (财经杂志 cáijīng zázhì), Caixin News (财新网 cáixīn wǎng), The Paper (澎湃 péngpài), China News (中国新闻网 zhōngguó xīnwén wǎng), and 18 other popular media outlets had roughly 41 articles that were deleted or blocked.

So, what were these articles like, and why did they get deleted?

Young Weekly looked at five elements, including the media that posted the articles, time the article was published, category of the article, the sentiment of the article, and the angle of the article. We analyzed these 41 articles that got 404’ed and have written an epitaph for them.

1. Caijing Media occupies half the space

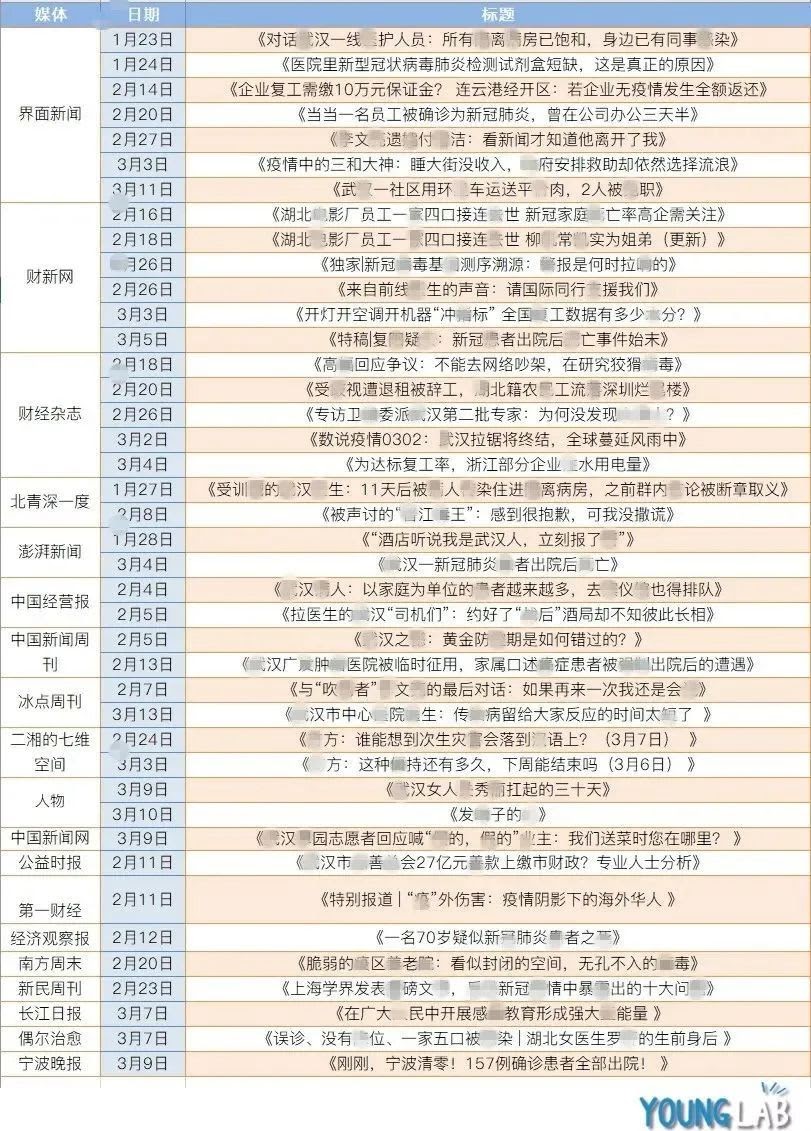

First, an image: A panoramic view of these 41 articles, their rough subject matter, the date they appeared, and where they appeared:

Among the deleted articles — from Jiemian News (界面新闻 jièmiàn xīnwén) on January 23 (“Wuhan medical personnel: All isolation rooms are filled, and colleagues around us already infected”) to an article posted on People’s Wechat called “Whistleblower” to Chinese youth magazine Freezing Point Weekly’s March 13 article, “Wuhan Central Hospital doctor: The infectious disease didn’t give us enough time to react” — some were deleted for reasons unknown, some were quickly forgotten, and some have remained in the public’s recollection.

Leading the way with disappeared articles are Jiemian News, Caixin, and Caijing Magazine, all of which are top business media publications. Other leading business publications, including China Business (中国经营报 zhōngguó jīngyíng bào), The Economic Observer (经济观察报 jīngjì guānchá bào), and China Business Network (第一财经 dì yī cáijīng) had articles that were scrubbed as well.

Of the 18 publications represented, a third of them were business media. The contribution of business media to epidemic reporting cannot be ignored.

2. Articles disappeared almost every day

On January 20, Zhōng Nánshān 钟南山 (the scientist who discovered the SARS coronavirus) appeared on CCTV’s News 1+1 and told host Bái Yánsōng 白岩松 that human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus was definitively possible. This gradually attracted the attention of the Chinese people. Two days later, on January 23, Jiemian News published the aforementioned article, “Wuhan medical personnel: All isolation rooms are filled, and colleagues around us already infected.” From that point until nearly two months later, March 13, news reports were deleted one by one. From February 4 to 27, and in the 12 days between March 2 and 13, at least one article was erased from the internet every day.

On February 26, Caixin posted “Tracking the source of the novel coronavirus gene sequencing: When does the alarm go off” [Ed’s note: see a translation of this article here], and “Sounds from a doctor on the front line: International colleagues, please help us.” In addition, Caijing Magazine posted “Interviewing China Health Commission experts: Why didn’t they discover human-to-human transmission?” These articles addressed why relevant departments did not report on the epidemic’s early stages, whether the China Health Commission’s early studies were properly conducted, and other similar inquiries. All three of these articles were inaccessible within short order.

3. Articles that focus on doctors and patients

Looking at the content of the articles that were deleted, their subjects most often included doctors, patients, and societal problems (including Wuhan people who were discriminated against, Chinese people who ran into difficulty internationally, etc.). Other articles featured topics such as returning to work after Chinese New Year, the government, why the optimal date for controlling the virus’s spread was missed, supplies, the state of the epidemic (inside and outside of China), the work of volunteers, donations, and companies, to name a few.

Deleted articles most often featured the viewpoints of doctors. Some were interviews of doctors, or interviews with their relatives and friends, and of course, there were articles about doctors risking their lives to fight the coronavirus. Other topics included commemorating doctors, and reports of the hard work they were putting in.

Within the reporting of doctors, whistleblowers attracted a ton of attention. For example, People’s March 10 article titled “Whistleblower” (发哨子的人 fā shàozi de rén) attracted an enormous amount of public attention. The regrettable thing is it was blocked only a few hours after being posted, though it still lives on in hundreds of different formats online.

A screenshot of People’s Wechat account

After “Whistleblower” was blocked, Wechat Moments was flooded with mutated versions of this article — for example, in foreign languages, Morse code versions, illegible script, etc. [Ed’s note: See this China Digital Times post.] Posting on this phenomenon on Weibo, the Shenzhen University Communication School’s special lecturer Cháng Jiāng 常江 said, “This isn’t a party, these aren’t jokes, and this definitely isn’t performance art. This is anger, shame, and humiliation.”

4. Dispatches and in-depth reporting lead the way

Looking at the categories of the disappeared articles, dispatches are the most common, followed by in-depth reporting, with the rest including short info pieces, diaries, and data.

These reports tend to rely on interviews, with stories straight from those who experienced them, reflecting society’s urgent, hidden, unresolved problems during the epidemic period. The stories in these reports are most often tragedies, and carry the strong subjective feelings and negative emotions of the interviewees.

In addition, these articles also expose mistakes in decision-making, and the disastrous aftermath of these mistakes. On February 5, China News Weekly posted the article, “Wuhan’s regrets: How did we miss the golden period for stopping the disease’s spread?” which exposed the dereliction of duties of relevant departments.

5. Articles mainly negative in nature

Regarding the sentiment of the disappeared articles, we have those which touch on the government’s strategic blunders, the difficulties of Hubei residents, and give pessimistic views about the epidemic — in other words, articles which tilt toward the negative.

Take, as an example, an article posted on Beijing Youth Daily’s public account (北青深一度 běi qīng shēn yīdù) about whistleblower Lǐ Wénliàng 李文亮, titled, “The admonishment of a Wuhan doctor: In an isolation ward 11 days after being infected, while before, discussions in group chats taken out of context,” suggested through Li’s own words that Wuhan’s relevant departments didn’t attach enough importance to the situation before it became an epidemic.

The article disappeared before long.

Among the deleted were a few articles that can be considered as taking the right approach, but which attracted waves of public criticism — such as an article posted on March 7 on Chang Jiang Daily titled, “Wuhan citizens are heroes among the people, and are also citizens who understand the meaning of gratitude! Wáng Zhōnglín 王中林 (Chinese-American physicist): Expanding gratitude education will create more positivity” — and were misunderstood by the public.

In addition, some articles were deleted for using incomplete data, such as a March 3 article from Ningbo Evening News titled, “Just now, Ningbo is good to go! All 157 patients have left the hospital!”

It’s quite common for Chinese publications to have their articles censored during regular reporting, but cases like this have seen a significant increase in the media coverage of COVID-19. These articles were “forced to disappear” because of false information, excessive negativity, or other policy-related reasons.

We can’t deny that some of the deleted articles have their flaws, but the overwhelming majority had extraordinary value, and forced readers to reckon with the epidemic itself as well as the deep-seated society problems that the epidemic exposed. The media today is using its limited resources to dive bravely into the abyss, accepting the pains of society in order to find the thorny underground.

Removing the thorns hidden in the depths, taking on the pain of society’s dark side, the media uses what limited power it has to reveal the truth, charging into the light. Although the articles discussed today were only with us for a short time, a place will be forever saved for them in history.