‘Your mom is dead’: The origins of the Chinese internet slang NMSL

It started in 2015 with Sūn Xiàochuān 孙笑川, a Sichuanese construction worker who livestreamed League of Legends games on a channel belonging to his friend. Now, "NMSL" is ubiquitous on the Chinese internet. How exactly did that happen?

Illustration by John Oquist

If you followed the recent meme war between Thai and Chinese netizens, you probably encountered the slang NMSL, an acronym for nǐ mā sǐle 你妈死了 — or in simple English, “Your mom is dead.”

In précis, the Thai girlfriend of a Thai-American actor retweeted a conspiracy theory that the novel coronavirus originated from a lab in Wuhan, which upset some people on the Chinese internet. It was later revealed that she had suggested, on social media, that Taiwan was not part of China. Chinese nationalists began bombarding the couple with angry tweets, which precipitated a China-Thailand cyber battle.

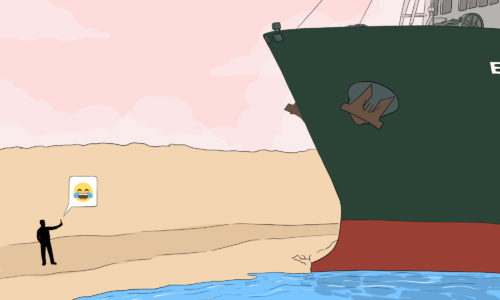

The acronym NMSL gained international attention during this time, for the frequency of its appearance. Trolls spammed these letters, often in retort to pro-Taiwan and pro-Hong Kong posts. But it backfired: these trolls soon found themselves trolled with their own letters, in meme form:

But what exactly is “NMSL,” and how did it come to be?

The birth of a subculture

It started in 2015 with Sūn Xiàochuān 孙笑川, a Sichuanese construction worker who livestreamed League of Legends games on a channel belonging to his friend, Lǐ Gàn 李赣.

Sun wasn’t a particularly good gamer, and sometimes he appeared dull on screen. When viewers on the streaming platform Dòuyú 斗鱼 criticized him, Sun snapped back with the most aggressive insults. But his curses consistently followed humorous, surprising, and unusual patterns, mixed with Sichuanese slang. Ni ma sile — “Your mom’s dead” — he once famously said to his viewers. “I’m your brother. We’re both your mom’s son. Your mom’s dead, OK?”

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

It didn’t take long for these verbal fights to become a focal point of Sun’s streaming, as viewers flooded to his channel to watch him insult people. Seeing Sun as a clown of sorts, his followers called themselves hāifěn 嗨粉, which is the way Sichuanese people pronounce the word hēifěn 黑粉 — fans who praise someone in order to shame them. Because his viewers jokingly called him Sūn gǒu (孙狗, Sun the Dog), they referred to themselves, in a playfully self-denigrating way, as gǒufěnsī 狗粉丝, “dog fans.”

Goufensi imitated Sun’s vulgar vernacular, often using acronyms and emojis in lieu of certain characters that might trigger keyword filters or censorship. For example, mā 妈 (mother) was often replaced with , the emoji for “horse” (马 mǎ); another common character for slurs, bī 屄 (vagina), was subbed out for the beer emoji , i.e., pí 啤, which is how Sichuanese people pronounce the character 屄 (vagina). And of course, NMSL is used instead of ni ma sile. This evolved into a meme subculture known as chōuxiàng 抽象 (“abstract”), named after Sun and Li’s studio. It quickly expanded, and its unconventional language patterns became almost ubiquitous on the Chinese internet. (There is a Wikiquote page dedicated to it.)

Sun may have been the inspiration for this subculture, but he himself was often the target of jokes. To embarrass him, his followers often invoked his name in unrelated incidents to baffle those unfamiliar with these memes. When a man violently assaulted a 93-year-old street vendor in Hangzhou back in 2016, some goufensi tagged Sun’s handle under the related Weibo posts, suggesting that Sun was the suspect. Sun’s name and photo began to appear below more social media posts completely unrelated to him, often with the caption, “The suspect has been found; it’s @带带大师兄 [Sun’s Weibo account].”

The goufensi often trolled other fan groups using inside jokes. When one Weibo post introduced the contestants of The Rap of China, it mistakenly referred to rapper Sūn Bāyī 孙八一 as Sun Xiaochuan. When Chinese singer Cài Xúkūn 蔡徐坤 was injured by laser pointers in 2018, they tried to persuade Cai’s fans that NMSL actually stood for “Never Mind the Scandal and Liber.” (This was written in English — we presume “liber” is “libel,” though we don’t know why it’s misspelled.) Soon after, “NMSL” became a trending topic on Weibo, as gullible fans chanted “Cai Xukun NMSL” in group chats, in support of their idol. (How “Never Mind the Scandal and Liber” is meant to be a statement of support, we can’t explain, exactly; idol worship culture is weird.)

The Chinese government largely disapproved of chouxiang culture. “Behind this phenomenon is a new type of cyber violence,” an article on Guangming Daily, a state-owned paper, remarked. “It isn’t characterized by direct attacks. Rather, [these goufensi] disguise themselves as various groups to create new battlefields, in an attempt to involve other netizens in turmoil, before they pull away and applaud.”

“It’s worth noting that for many young people who are not yet mentally mature, the expressions of goufensi have become a symbol for being different and unique. As they enjoy the sense of group superiority brought by such ‘cant,’ they’ve become a new generation of cyber mob,” the article added, calling for more internet supervision.

Goufensi today

Sun’s streaming career in China came to a halt in January 2018 when a viewer wrote him a song — as a joke — which Sun played on his channel. The lyrics, as it turned out, formed an acrostic: the first characters of each line, when linked together, made a reference to the Falun Gong, a spiritual organization banned by the Chinese government. Soon, Sun found himself barred from several livestreaming platforms in China.

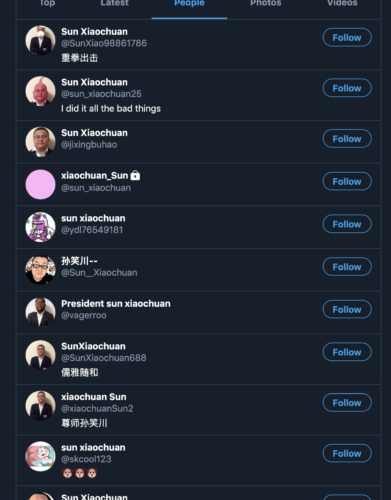

But his spirit lived on. Goufensi have continued to create chaos and confusion, even in their trolling overseas. Beginning last year, accounts with identifiable chouxiang features — photos of Sun Xiaochuan and tweets with recognizable language — began to emerge on Twitter. U.S. intelligence agencies have been warning about Chinese bots on Twitter, but it’s important to understand that a lot of accounts that look like bots are in fact manned by real people — people who might, for example, be goufensi. Ju Huo, a Chinese-Canadian software developer, wrote a tool to identify these profiles.

Just like their behavior on Chinese social media, these trolls often satirized anti-Beijing tweets by involving Sun in unrelated events; one tweet, for example, claimed Sun was a CCP agent who forced the Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong to work for Beijing.

This isn’t the first time a subculture has become nationalistic in nature. When Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén) was elected for the first time in 2016, Dìbā 帝吧, a subforum on Baidu known for its large number of subscribers and its history of flooding other forums, encouraged angry Chinese to circumvent internet censorship and post provocative memes and stickers on Taiwanese Facebook pages. The incident was later known as “Diba Expedition.” While Diba was originally founded to mock Chinese soccer player Lǐ Yì 李毅, over time it deviated to become a discussion board for current affairs.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, internet-savvy Chinese youth are becoming more nationalistic, and they are happy to express their fury over how their nation is treated by the outside world. It isn’t surprising that chouxiang culture is gaining traction among young, internet-savvy Chinese; the incorporation of subcultural memes into online nationalism is a manifestation of that growing discontent. To anonymous mobs on the internet who choose to express their anger through direct, coarse insults, winning the argument isn’t at all important; frustrating their mark is the entire point.

Goufensi are the ultimate trolls, aiming for neither understanding nor communication. At the end of the day, if they’ve humored themselves and vented their rage, it’s all that matters. Perhaps, then, we as observers should be wary of how much we read into their actions.