‘Stars 1979’: The moment Chinese art changed forever

In 1979, a group of Chinese artists made history by shattering historical precedent, organizing a pop-up exhibition of contemporary (and subversive) art outside the National Art Museum of China in Beijing. The exhibition was shut down within three days, but in that short span, the Stars secured their legacy forever.

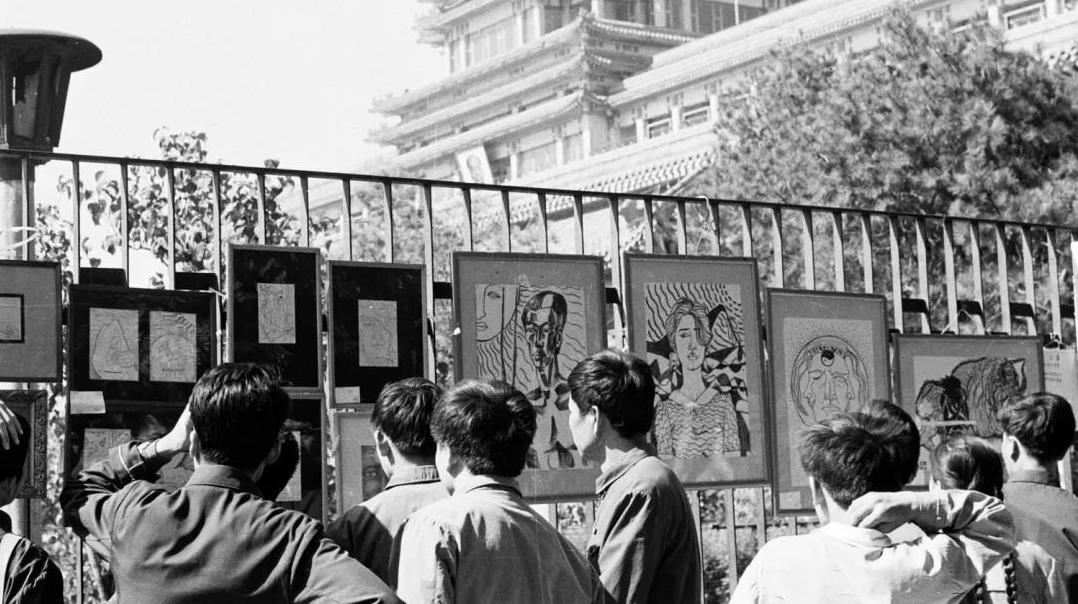

The best-known story in Chinese contemporary art concerns an exhibition held in a park with paintings and sculptures hung on fences and nailed to trees, and which lasted fewer than three days. Yet this unofficial exhibition attracted thousands of visitors and altered the shape of art in China for years to come.

At least, that’s how the story goes. But is it accurate? A new exhibition at OCAT Research Center in Beijing, Stars 1979, strives to examine this story in greater detail. Opened on December 20, closed during COVID-19, reopening May 6, and running through June 28, Stars 1979 marks the ninth exhibition on the “Stars Art Group” (星星 xīngxīng), a collective that launched China’s artistic avant garde.

Who were the Stars, and how do we explain an enduring fascination with an exhibition that was held more than 40 years ago?

![]()

![]()

On the morning of September 27, 1979, 23 artists arrived at a park on the east side of the National Art Museum of China and hung more than 100 artworks on the fence and surrounding trees. Their styles and mediums marked a radical departure from the Socialist Realism of Mao-era public art: oil paintings after Picasso hung alongside post-impressionist portraits, ink and wash paintings, marker drawings, woodblock prints, and sculpture. The artworks inevitably attracted the attention of hundreds of passersby in addition to a budding literary and artistic community — and, before long, the Dongcheng Public Security Bureau. On September 29, the artworks were confiscated by police.

Immediately afterwards, Stars founders Huáng Ruì 黄锐, Mǎ Déshēng 马德升, Wáng Kèpíng 王克平, and Qū Lěilěi 曲磊磊 met with members of Beijing’s underground literature scene and the closely-related democracy movement. They planned a protest march for a few days later. On October 1, the 30th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, they marched under a slogan that would forever link the Stars with politics: “We want political democracy! We want artistic freedom!”

Despite holding only two official exhibitions in addition to the first outdoor event (one of these two featuring a 22 year-old Ài Wèiwèi 艾未未), the Stars attracted outsized publicity and quickly won acceptance, however temporary, within the establishment. In the 40 years since, at least eight retrospectives have been held: in mainland China, Hong Kong, Japan (twice), Germany, France, and the U.S.

The Stars phenomenon was not only a departure from the past but a bellwether for China’s cultural development over the 10 years to follow. The 1979 exhibition’s wide variety of styles and media was followed by an explosion of artistic practices across the country, which are usually referred to as the “1985 New Wave Movement.” Within a year of their emergence, the Stars’ work went from the fence of the National Art Gallery to within its prestigious halls. This remarkable transition presaged the New Wave Movement’s defining China/Avant-Garde exhibition, with its own unorthodox art and performance, at the same institution in 1989. By 1984, most of the important Stars artists had emigrated abroad after the launch of the Campaign Against Spiritual Pollution the year before. In 1989, four months after officials shuttered the China/Avant-Garde exhibition, demands for political democracy were answered at Tiananmen, followed by another exodus of artists.

The OCAT exhibition, in examining this period, follows a trend at the highest level of the art world, whereby abstract paeans to genius are replaced by social and historical context. The Stars were the first art movement of the reform era to deliberately seek out public attention and response, and to link their exhibition to activist demands for political democracy. Among the excellent materials on view at OCAT are handwritten comments left by Beijingers who attended the exhibition. According to Holly Roussell’s catalogue essay, this sort of public engagement was central to the Stars’ approach.

![]()

![]()

The 1979 exhibition was a bold political challenge: critics and admirers alike saw it as an obvious response to the extremes of the Cultural Revolution and the detested “cultural tyranny” of the Gang of Four. From 1949 until the middle of the 1970s, visual art, literature, and drama in the People’s Republic of China was considered a political tool. For nearly 30 years, changes in the cultural sphere almost always reflected changes in the political situation.

The OCAT exhibition is split into four sections: a timeline detailing political and artistic activity from 1976 to 1980; a section explaining the Stars’ relationship to the literary journal Today; a collection of personal notes, documents, and some recordings, mostly from the period between the first and second official exhibitions; and a “conceptual reconstruction” of the unofficial exhibition outside the National Art Museum that features original and reproduced artworks.

Curators Wū Hóng 巫鸿 and Holly Roussell (容思玉 Róng Sīyù) emphasize a historical perspective, relying upon photography and records kept by the artists to recreate the exhibition as a “historical event,” according to Roussell. Only 90% of the outdoor exhibition was captured in photographs and therefore the reconstruction at OCAT features 126 of the 150 or so artworks exhibited in 1979. Some works are not included, even as facsimile, because they have been lost or destroyed and no high quality photographs remain. Of the 126 artworks in the present exhibition, 18 are original. In its entirety, the exhibition’s layout adheres to the historical record. “It was fundamental for our concept that as many of the artworks from the original show could be presented, whether that be original works or as photographic reproductions, so that visitors could have a sense of the outdoor hanging’s form and content,” Roussell told The China Project. The exhibition’s explicitly historical perspective might have run the risk of using the artworks only to illustrate an historical premise. Does an emphasis on history, in combination with an unavoidable dearth of original works, imply that the significance of the artworks is rooted primarily in historical knowledge rather than a physical encounter with the work? If most originals are unavailable, how can we see the Stars’ art the way it was seen in 1979?

Archival documents, an indispensable component of the latest Stars retrospective, provide an answer. Alongside the notes left by Beijingers are a multitude of photographs and reproduced editions of Today’s nine issues. Other items hint at the non-political obstacles faced by Stars artists: an original woodblock used by one of the few women members, Lǐ Shuǎng 李爽, gives an idea of the limited, small-scale materials on hand at the time.

Nonetheless, when artists Qu Leilei and Bó Yún 薄云 discussed their work with the audience at an opening reception in December, just as they did in 1979, it is nonetheless a difficult task to experience these works and the exhibition the way that most Beijingers experienced them: as something new, even radically so. Ironically, understanding the historical background of the exhibition means trying to unlearn art history from before 1979. It means trying to see Huang Rui’s Yuanmingyuan series the same way as someone with little or no familiarity with modern art — but very likely a strong sense of loss caused by more than a decade of violent social upheaval — might have seen it. It means an attempt to notice that familiar imagery — in Bo Yun’s Ah! Great Wall or Wang Keping’s Long Live! (featuring Mao’s Little Red Book) — was presented in an unfamiliar visual language, one incorporating not only new visual styles but emotional content, like mourning and fear, that was relatively new to public art in the late 1970s.

In this way, Stars 1979 might help inscribe the Stars into a more accurate, global history of modern art. Something of modern art’s original power to excite and shock audiences is recaptured at OCAT precisely because the exhibition emphasizes a feeling, shared by the poets of Today, that by all accounts demanded expression. “At that time I felt that anything was possible, anything happening could be shown,” Huang Rui told critic Gāo Míng lù 高名潞 in 2007.

At the same time, modern art is related but not reducible to politics, and the same goes for the Stars. As Philip Tinari, director of the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, points out in a short essay, over the past 40 years, as more Chinese artists have achieved international recognition, foreign art critics have often emphasized any hint of political critique — assumed to be directed at the Chinese government, rarely elsewhere—within their works. But only eight of the 23 exhibiting Stars artists participated in the protest march on October 1. Even Huang Rui, the mastermind of the exhibition, initially opposed the march and advocated accepting a compromise extended by Liú Xùn 刘迅 and the Beijing Artists Association (Liu had proposed an outdoor exhibition at Zhongshan Park supported by the BAA). Faced with a vote in support of the march, Huang chose to stand with the artists who voted in favor.

Despite the multitude of retrospectives, some fear for the Stars’ legacy. Huang Rui himself— one of the first artists to reside in the now-commercialized 798 Art District — often seems bitter that critical attention is lavished on the ‘85 New Wave while the Stars and their art are forgotten. (According to Roussell, Huang personally coordinated the preservation of many of the archival documents included in the OCAT exhibition). In 2007, for example, when Today Art Museum and the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art simultaneously hosted exhibitions on the Stars and 85 New Wave, curators referred to the former as the “origin point,” reserving “the birth of Chinese contemporary art” for the latter.

The story, however well-known, in which the Stars are the “original” avant-garde is perhaps not the ideal way to cement their legacy within art history after all. Instead, they might best be remembered as yet another chapter in the development of modern art, another of its many encounters with a public audience, and a convincing testament to the curious and resilient attraction of new art.

![]()

Stars 1979 will run at OCAT Research Center in Beijing from May 6 to June 28. Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. (closed on Mondays).