His dictionaries taught Chinese to the Uyghur world. Then he was taken away

Hüsenjan was a Chinese state employee — and member of the Chinese Communist Party — tasked with creating dictionaries for the Uyghur language. His work couldn’t save him.

The Chinese-Uyghur finance dictionary was huge. It must have been made out of A3-size paper, almost 11 inches by 17 inches. When she held it in her hands, Gulruy Asqer remembers it feeling like two big bricks. It was a lot to carry. Her brother had given it to her as a farewell gift before she moved to the United States.

“I complained that it was so heavy,” she said. “I just left it in the center of the living room rug with all of the other things that I thought were too big to carry.” She had the rug, which was a wedding gift, shipped to the U.S. She left the dictionary behind.

“I can imagine how disappointed he must have been to see me abandoning that dictionary,” she said, thinking back. “I didn’t value it at all.” Her brother, Hüsenjan, who has published more than 40 dictionaries, was particularly proud of it since Gulruy’s major was finance. He thought she would really find it useful in her new life in America.

Reminiscing over the choices she made, deciding which things to pack, which things to ship, which things to leave behind, Gulruy is ashamed. “Now I value Uyghur dictionaries so much,” she said. “Today the government is burning them.”

That massive dictionary, funded by the banking system, offered Uyghurs a promise of commensurability. A way of entering the mainstream Chinese economy, one word at a time. Words like zhīpiào 支票, the Chinese word for “check,” or huípiào 回票, the Chinese word for “rebate,” were unknown to Uyghurs. “There was so much need for this kind of knowledge,” Gulruy said.

Indeed, in 2014 Kudret Yakup, the Harvard-educated founder of the Ürümchi-based Uyghur investment firm Erqal Capital, estimated that there were likely only 1,500 active registered companies owned by ethnic minorities in Xinjiang. Out of that number, only around 500 were commercially viable — meaning there was approximately one viable company for every 30,000 Muslims in the region. Since 2014, Erqal Capital and hundreds of other Uyghur-owned companies have been closed. Like the dictionary that would have given them the lexicon to do business in Chinese, they have vanished.

In 2019, Gulruy’s brother, Hüsenjan Esker (玉山江·艾斯卡尔), Vice Chair of Terminology and Senior Translator of the Ethnic Languages Committee Office (语言委员会名词术语办公室 yǔyán wěiyuánhuì míngcí shùyǔ bàngōngshì) of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, disappeared.

A bilingual dictionary written in the 1070s was one of the first literary works that Uyghurs claim as their own. The Compendium of the Turkic Languages, written by Mahmud Kashgari, placed Turkic languages — what would later become Uyghur, Uzkbek, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz, among others — in conversation with complex Arabic linguistics. It showed that Turkic languages had been codified as a distinct form in opposition to other contemporaneous languages and knowledge systems. Kashgari notes that the Uyghur dialect was one of the purest because it was the least mixed with Persian. In the dictionary, Chinese appears to be a distant language far on the horizon.

Nearly 1,000 years later, leading translators like Hüsenjan, employed by the Chinese state, still leaned on Mahmud Kashgari’s dictionary as an original source for Uyghur terms. For instance, in an episode of the Uyghur-language Xinjiang TV show Cultural Oasis (Uy: Medeniyet Bostani), embedded below, Hüsenjan’s boss at the Xinjiang Ethnic Languages Committee, Alim Kheseni, notes that the Chinese term for “coffin,” guāncai 棺材, had no equivalent in 20th-century Uyghur. Because coffins were associated with non-Islamic traditions, Uyghurs had stopped using it. But by going back to Mahmud Kashgari’s dictionary, authors like Hüsenjan were able to find that in the 11th century, just two centuries after Islam arrived in the Uyghur homeland, Turkic peoples had a word for coffin, üke. By excavating this 1,000-year tradition, they were able to bring Uyghur traditions in conversation with the contemporary language environment.

Dictionary writers are responsible for the living edge of language. In Northwest China, the rapid establishment of Chinese state education systems and publishing houses meant that Hüsenjan had to invent new words to help the new world make sense for Uyghurs. He had to set standards for how to refer to things that became ubiquitous in Uyghur life. For instance, he invented the Uyghur term for “ID card” (Uy: kimlik), which literally means “who one is,” to replace the much more awkward “qualifications certificate” (Uy: salahiyet guwahnamisi). In the 2000s, he combined the Uyghur word for “pocket” (Uy: yan) with the Russian loan word for telephone (Uy: tılıfon) to form the word “yanfon” — the word every Uyghur uses to refer to their cellphone today. And he created the word “tizginek,” which means “remote control,” by combining “tizgin” — or “control” — with the suffix “nek,” which means “a small thing.”

Hüsenjan was a state employee. His task was to introduce the broader contemporary world to Uyghur society through the Chinese language. In the 2000s, as Xinjiang’s education system shifted from Uyghur to Chinese, his mandate was to provide Uyghur students with tools to learn Chinese. As he said on a TV show (see below), “With regards to Uyghur dictionaries, the government has really been supporting this effort and has done a lot of work to support our organization (the Ethnic Language Committee).”

Excerpts from Hüsenjan Esker’s appearance on the Xinjiang regional TV show Cultural Oasis (with English subtitles).

He acted with a lot of care to show his loyalty to the state, and to the project of bringing Uyghurs into Chinese mainstream society. After the mass violence of July 5, 2009, he appeared on state TV and made a statement about how the government was doing a good job in “stopping the separatists.” In the following years, when he was asked to go to Southern Xinjiang to teach Uyghurs political ideology, he went without complaint as a volunteer. “He tried to do everything right,” Gulruy said.

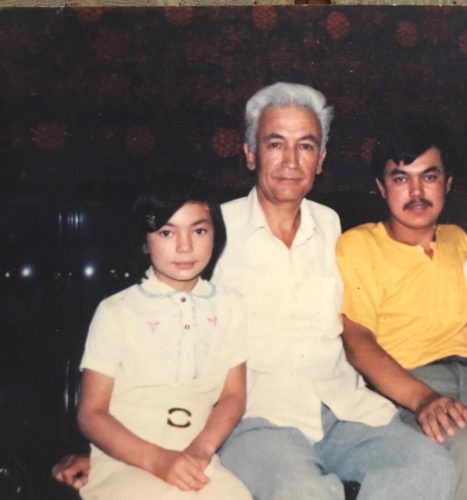

In fact, Hüsenjan’s support for the state became a source of tension in their family. Gulruy recalls, “My father was never satisfied with my brother. My father was very charismatic. He could order people to do things and they did it. He was never satisfied with Hüsenjan; he was so quiet and studious, and then he became a Party member.”

This attitude was not unique to her father. Lots of Uyghurs did not see the value in Hüsenjan’s project, including Gulruy. Instead, they saw someone working for the government and towing the Party line. “For a long time I wasn’t proud of my brother when I lived over there (in Xinjiang). I didn’t know why he was so dedicated to such tedious work,” Gulruy said. “Then I began to realize how important his work is in preserving language.”

She remembers the first moment she realized how important her brother was to the future of Uyghur society. It was at a Xinhua bookstore near Yan’an Street, the largest bookstore at the center of Uyghur urban life in Ürümchi:

“I went there to buy some books for my daughters. We went to the second floor and in the middle aisle, where they had all the reference books, my husband said, ‘Oh look, here is your brother’s name.’ It was his dictionary. So then we started looking at other dictionaries. His name was everywhere. Hüsenjan Esker. We opened the dictionaries one after another and we saw his name in all of them. I was so proud. The next time I saw him, I told him we counted more than 30 of them. I said I wanted to scream in the bookstore, ‘My brother’s name is everywhere!’ He didn’t say anything, he just gave me a quiet smile. He was so proud. And I was proud of how humble he was. My father had already passed away. I wish he could have seen this.”

Remembering this in 2020 made Gulruy think about all of the time she spent with Hüsenjan helping him with his work when she was young and still living at home with her parents.

“He liked to drink very red dark tea, a kind of ‘brick tea’ (Uy: hish chay). It is old people’s tea, really. It has stems in it, too. It comes with paper wrapped around it. You have to get a knife to break it apart. My father and mother used to do it. Hüsenjan would stay up. He made me make tea for him all night. He said he would pay me 5 yuan, and I would say, ‘No, 10 yuan.’ He would pay me to make the tea and help him search for words. I was his little research assistant. We drank the tea out of little bowls (Uy: piyale). I still remember them, they had Uyghur flowers inside. The tea had to be hot. If it would cool down too much he would say, ‘Heat it again.’”

Hüsenjan taught Gulruy to take herself seriously. Their work was important, and to do it right, they needed to look and act the part. She remembers,

“Back then he liked striped shirts and light-colored pants. He really liked to dress up. My father was like this too. If I came to his office a little bit messy he would yell at me. He felt like appearances really mattered. My father always wore a tie. I think now that this was probably him trying to live up to my father’s expectations.”

Hüsenjan took Gulruy under his wing. He pushed her to study hard and to achieve things that even he had not been able to. “He would buy me English dictionaries. He said, ‘It is impossible to sing in English like a nightingale overnight.’ He told me, ‘When your friends play around, you study.’”

Over time, all of his coaxing began to rub off, and Gulruy began to succeed academically. She even started to resemble her older brother. “When I took the high school entrance exam, his classmate — the proctor of the test — recognized me, asking, ‘Are you as smart as your brother?’ A man who was a total stranger said this to me. I was so surprised. He said, ‘You look exactly like him. Kichik Hüsenjan’ (little Hüsenjan), he called me this.”

Gulruy first learned that her brother had been taken in 2019, when she saw his name on a list of intellectuals who had been seized by the state. She started to have nightmares about him. In her dreams, he was given the long coat reserved for the most honored members of Uyghur society; then, in the midst of the ceremony, police dressed in black and carrying machine guns came and took him away. Because her relatives had stopped communicating with her directly in 2017, she had no way of finding out what was happening.

“I sent my relatives WeChat invitations hundreds of times. Eventually one of my relatives responded. She said Hüsenjan was taken. There were no men left in the family, since my nephews were taken as well. In January 2019, he returned to his house with the police. He told his wife to prepare his clothes and medication. Then he just disappeared.”

Gulruy could tell that her relatives were terrified to speak with her. They stop answering her calls. The only tie that connected her to her home in Ürümchi was an occasional conversation with her mother once every several months. At the other end, her mother often made her eight-year-old nephew answer the phone. Gulruy’s mother would tell him to say, “Tell her grandma is not at home.” Gulruy said, “She knew that I could hear this. It made me sad, but it also made me smile. She was trying to communicate with me in the only way she knew how.”

From Gulruy’s perspective, what has happened to her family is an indication of how widespread state violence has become in the Uyghur region. She said, “We are religious, sure. We are Muslim. But that just means that we pray and follow the basic rules of Islam. We are all college-educated, but we pray at home. My oldest sister did teach the children to pray and they listened to the Qur’an on an mp3. This is why my nephew was taken. Hüsenjan didn’t pray at all, he was a Party member. But still, they thought he was protecting our ethnicity.”

Gulruy believes that Hüsenjan was detained because of his work on a dictionary of Uyghur place names. Because the Uyghur names for places carry a claim to native sovereignty, his effort to collect them and pair them with their Chinese equivalents may have been deemed to have been a “separatist” activity. Unlike Mahmud Kashgari, who wrote the first Turkic dictionary nearly 1,000 years ago, Uyghurs are no longer allowed to write their own history. Hüsenjan’s audacity to systematically document how Uyghurs refer to their homeland outweighed decades of Party loyalty, decades of service to the regional government.

It is difficult to erase a knowledge system. Hüsenjan’s dictionaries taught a generation how to think about their world in the Chinese language, but it also showed them that their social world was equal to a Chinese social world. “Hüsenjan and the other translators started from nothing, to build this,” Gulruy said. “They wanted us to be just like other nationalities. We needed language for all of the modern professions, and they gave it to us.”

Gulruy understands now why Hüsenjan worked so obsessively through the night cataloguing the Uyghur language. “He was working beyond his job. No one gave him orders. He was motivated by himself.” She knows that some people recognized this in him. One of his colleagues, the sociologist Zulpikar Barat, who also reportedly disappeared during the purge of intellectuals, told her, “We didn’t need to edit his work. When I got his manuscript, the boss would say, ‘If it came from him you don’t have to edit it.’ if it came from him it was ‘spotless’ (Uy: pakiz).”

When she thinks about him now, she remembers how they used to watch Tom and Jerry cartoons during breaks in their late-night dictionary writing sessions. She watches it now when she thinks of him. “It hurts me so much to watch it. I miss him so much. He doesn’t laugh and smile a lot. Watching Tom and Jerry was the one time when he laughed a lot. He liked it more than me. Most of the time he is very calm. He is that kind of man.”

In April 2020, Gulruy learned that Hüsenjan had been returned to his home and was now under house arrest. According to news that was relayed to Gulruy, “He looks fine, but he looks like a patient who has just been released from the hospital: a little thinner, his voice a bit weaker.” Judging by the process used in a number of other detainee-rehabilitations, it is likely that Hüsenjan will be on probation for at least six months. He may be placed in some form of state-approved employment during that time. The Ethnic Languages Committee Office where he worked has been replaced by a more generic title: the Translation Bureau (Ch:翻译局 fānyì jú ). It is unclear if he will be allowed to return to his dictionaries.

Darren Byler’s Xinjiang Column is published on the first Wednesday of every month. Previously:

‘Heaviness in the stomach’: A Uyghur daughter alone in America on her birthday during a pandemic