Chinese parents who lose their only child — a tragedy so common there’s a word for it

The death of a child is the ultimate tragedy. But in China, parents who lose their only child are a special case, especially if they gave birth during the country's one-child policy era. For many of them, their grief knows no end.

Scrolling through Hongyan’s (pseudonym) posts on the video app Kuaishou, almost all of them show her either staring vacantly at the camera or weeping in silence.

Hongyan lost her daughter — her only child — one and half years ago in a car accident, eight days after the 29-year-old got married. Hongyan’s hair turned gray overnight, and a live-streaming platform was the only place where she could find escape.

“The pain of losing my daughter eats me from inside every day, every minute,” she told me when I reached out to her on the app. “Only in the few moments when I’m keeping myself busy is my mind temporarily away from the pain.”

“Those who haven’t experienced the same loss will never understand the pain,” she added.

Since she began posting videos on Kuaishou about a year ago, Hongyan has attracted comments from other parents who know the trauma of losing an only child. Some have accounts like Hongyan’s, where they either weep or stare at the camera, doing nothing. One user, Lanhuacao, who lost her only son in early 2019, captions almost all of her videos with the text, “My son, my heart aches dreadfully from missing you.”

These mothers address each other as “sister,” signaling mutual empathy and implying a relationship as powerful as blood: They are now all shīdú 失独 parents.

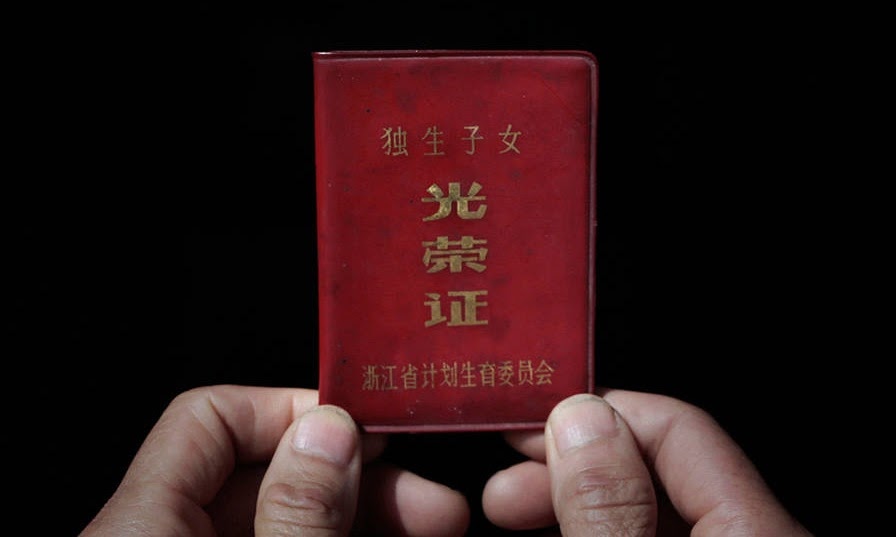

The word shidu, separated into its component characters, literally means “loss of only.” In this case, only refers to “only child.” It’s difficult to find the exact etymology of the word, but it’s likely that it came to being around 2000, when the first generation of parents who gave birth under the one-child policy — which was implemented nationwide in 1980 — turned 50. The horror of losing an only child began to get national media attention around this time. (Many years later, a movie would be made with a shidu couple at the emotional heart of the film: So Long My Son, released last year, has been hailed as a contemporary Chinese classic.)

Before being repealed in 2015, China’s one-child policy averted 400 million births, according to a government report, which credits the policy for the country’s economic development. “The successful imposition of our Family Planning policy postponed the world reaching 7 billion people by five years,” Máo Qún’ān 毛群安, then the spokesperson of the National Health and Family Plan Committee, is quoted as saying in the report.

But the benefits have come at a price, and like many things in China, the price has been borne by the people. According to a 2015 China News report, there were 1 million families as of 2012 that had lost their only child. The psychological devastation is compounded by the fact that Chinese parents have traditionally relied on their children to support them in old age, and the traditional value of “carrying on the family line” is still deep-seated in some regions. Most shidu parents also have no access to institutional support, and 60 percent of them suffer from depression, according to China News. Although awareness of mental health is increasing in China, it is not openly and widely addressed.

Tángrèn Zhīhuì 唐任之慧, a psychologist who focuses on shidu parents, said that only 20 percent of shidu parents have sought psychological treatment of any kind, with only 8.5 percent receiving professional psychological treatment or grief counseling.

Adding insult to injury, for many families, a child is the bond that ties many households together. Once the child is gone, the family breaks down, too. A 2017 report showed that 30 percent of couples filed for divorce after losing their child.

When China lifted its one-child policy in 2015 to curb an aging population and shrinking labor force, some shidu parents went hysterical. More than 700 shidu parents gathered in front of the National Health and Family Plan Committee to demand better welfare for shidu families.

“The two-child policy is like a handful of salt to our open wounds,” read one petition signed by a group of shidu parents. “We were deprived of the right to give birth, and now we’re bearing the consequence. The government should fulfill its promise to support us.”

While promoting its one-child policy, the slogan most often seen was this rhyming couplet: “Family Planning is good, the government will take care of the old” (计划生育好, 政府来养老 jìhuà shēngyù hǎo, zhèngfǔ lái yǎnglǎo). But the government hasn’t really lived up to that promise.

Generally, the government only provides 340 RMB ($48) per month to shidu parents over the age of 49 living in the city, and 170 RMB ($24) to those in the countryside. Parents in big cities like Beijing and Shanghai receive a little more, 500 RMB ($70) per month, which is far from enough to support basic living.

“There are three mountains in front of us: growing old without support, being sick without access to affordable treatment, and dying alone,” one shidu parent told Caixin.

And so, Shidu parents turn to social media for support. On the Twitter-like microblogging platform Sina Weibo, there are numerous accounts of parents who’ve lost their only children. One user’s profile reads, “Waiting to die in loneliness”; another: “How can I continue my life without you?” Li Xiaoguo, who lost his only son in a tragic murder, identifies himself in his bio as simply “Li Junjie’s father.”

Shidu parents also find each other in private groups and other social media platforms, and may gather in real life to share photos and stories of their children. Sometimes they simply need to shed some tears together, or vent emotions they otherwise conceal.

This community of shidu parents decided on a day, five years ago, to memorialize their children: April 2, 思独日 sī dú rì — “Only-Child Remembrance Day.” The commemoration is unofficial — you’ll hardly find a mention of it on the internet — but within the shidu community, its significance is undeniable.

This past April 2, one shidu mother posted a poem on Weibo, written in the voice of her late son. It reads:

A Short Letter from Heaven

Mom, today is an open day in heaven

Standing on heaven’s bridge, I look down on what was once my home

I look down on familiar faces — my families and friends

I see your face, Mom, in the middle of the crowd

You look a lot older…

My hands gently touch your graying hairs

I am lost in words, my eyes well up

Mom, I’m so sorry that I wasn’t able to take a moment to say goodbye

The breeze is my gentle touch

The rain is me saying I miss you

Above: Sāng Zhēn 桑珍 was 69 years old when Phoenix New Media (ifeng.com) collected stories from 19 shidu families, include hers. She was living by herself in a house with a leaky ceiling. She did all of the household chores herself.

Below are three more photos from Phoenix Media, with translated captions.