Young Chinese in the U.S. find political activism during COVID-19

During COVID-19, young Chinese expats and first-generation immigrants in the U.S. have become keenly aware of the importance of civic action. Many of them, during this period, have become more politically active than ever before.

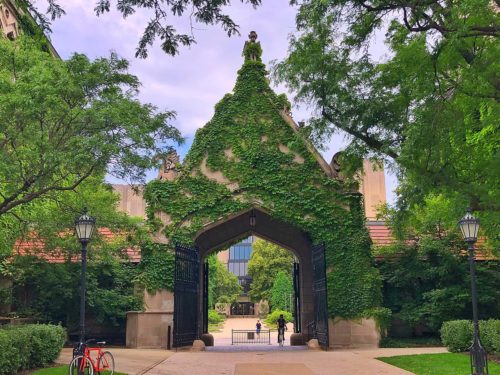

Amy Zhang’s heart sank in early March when she read in Food and Wine Magazine that New York’s Chinatown was “on life support.”

With the COVID-19 outbreak, Chinatown businesses started declining sharply in late January. By the time shelter-in-place orders were enacted in March, many shops in the neighborhood were already struggling to make ends meet.

Zhang, a New York-based journalist who was born in Beijing and grew up in Hong Kong, felt the urge to do something. She joined seven activists in March to organize a campaign to raise awareness of the situation. They called it Dumplings Against Hate. In a week, they built a website, set up social media accounts, and a GoFundMe campaign. Money poured in immediately. The team has since raised more than $50,000 to help struggling Chinatown businesses.

Zhang has always been involved in advocacy, but the sense of urgency to organize and speak up increased during the pandemic. When she graduated college in 2015, she had what she now thinks was a “romanticized” vision about shuttling between her birth country and host country and build cross-border educational and artistic collaborations.

“Now it’s like, can I even go back and forth?” she says. “The level we’re at now is like, ‘Do you see me as human?’ And then, ‘Do you believe that I, as a Chinese person, am not just carrying the virus automatically?’”

“What motivated [my organizing] is because I realized, here are these two countries with a huge understanding gap, and because I live between both countries so much, I hold some answers to bridge that gap, or might have some ways to facilitate that conversation,” Zhang adds.

While the pandemic has triggered xenophobia and racism against people of Asian descent in the U.S., it’s made young Chinese expats and first-generation immigrants aware of the importance of civic action. Many of them, during this period, have become more politically active than ever before.

Since February, multiple Chinese alumni organizations and local Chinese advocacy groups have raised funds and leveraged their ties to procure personal protective equipment (PPE) from China to donate to local hospitals. Civic-minded Chinese international students and expats have built websites to connect PPE providers and organizations in need and set up fundraising campaigns to help their local communities. Even though many of them came of age in a society and culture that discouraged them from politics, some are beginning to understand the importance of speaking up for their community.

Their efforts stand in contrast with an older generation of Chinese Americans who strive to be recognized by the rest of America. To “prove” their Americanness, some prominent community leaders have built an alliance, Chinese Americans United for America, that seeks to encourage more philanthropic activities and civic participation among Chinese Americans and, according to their website, “demonstrate Chinese Americans’ exemplary citizenship.” The group has kept a tally of nearly 700 grassroots organizations led by Chinese Americans that have donated PPE and funds adding up to $18.5 million to U.S. hospitals and institutions. Although the alliance’s co-founder, Yukong Zhao, acknowledges that Chinese Americans are sandwiched between U.S. and China politics, he insists on the alliance’s nonpolitical nature.

Wang Rui, a New York-based data analyst, has been engaged in an initiative similar to Zhang’s Dumpings Against Hate, called Send Chinatown Love. Using her bilingual skills, the 24-year-old native of Zhejiang Province set up a WeChat account for her group and worked as a community liaison to reach businesses in need of help.

A robust civil society in the U.S. encourages civic participation, Wang says, and growing political tensions — apparent in Donald Trump’s (often error-riddled) tweets at China and the Chinese diplomatic corps’s aggressive responses — motivated her to stay more active. “I probably wouldn’t have done this if I were in China,” she says.

Also in March, Cassandra Xia, who recently received her Master’s degree in political science from Columbia University and is due to start a law program in the fall, together with her husband translated into Chinese a guide to applying for the federal Paycheck Protection Program, a loan designed to provide a direct incentive for small businesses. She released the translation on both English and Chinese social media.

“Is what we did political engagement? I think so,” Xia says. “We are using social media and technology to bring more exposure to relevant issues at hand. Those of us who are bilingual and bicultural can bridge the gap between those inside and outside the firewall” — referring to the “Great Firewall,” a metaphor for China’s internet censorship apparatus.

Many of her Chinese friends and classmates in the U.S. are also pitching in, in ways big and small, Xia says.

“Our generation of Chinese students are in survival mode,” she says. “Forty, fifty years ago, the Chinese students who came here overwhelmingly majored in engineering and sciences. So many of us are studying humanities and social science. Once we don’t need to worry about surviving, we can afford to care more about public affairs and politics.”

Businesses run by young Chinese in the diaspora have also joined the effort. Junzi Kitchen, a fast-casual restaurant chain specializing in northern Chinese food, has raised more than $40,000 since March to deliver 4,000 free meals to healthcare workers in New York.

The young brand, founded by a group of Yale graduates from China, has a mission to bridge relations between China and the U.S. It finds itself in a tough spot in today’s political climate. “I don’t know if our bridge will survive the flood,” Junzi co-founder Zhao Yong says, referring to worsening U.S.-China relations.

Zhao’s pessimism is similar to that of many people I interviewed, but he remains hopeful that civil cultural exchanges can eventually win the hearts and minds of Americans, one meal at a time.

“Food is food,” Zhao says. “Hopefully, some of our American customers who like our noodles will try other Chinese cuisines, then they will see people behind the food, and once they see people from a different country as individuals, the hatred will lessen.”