Qi Baishi, the Picasso of China

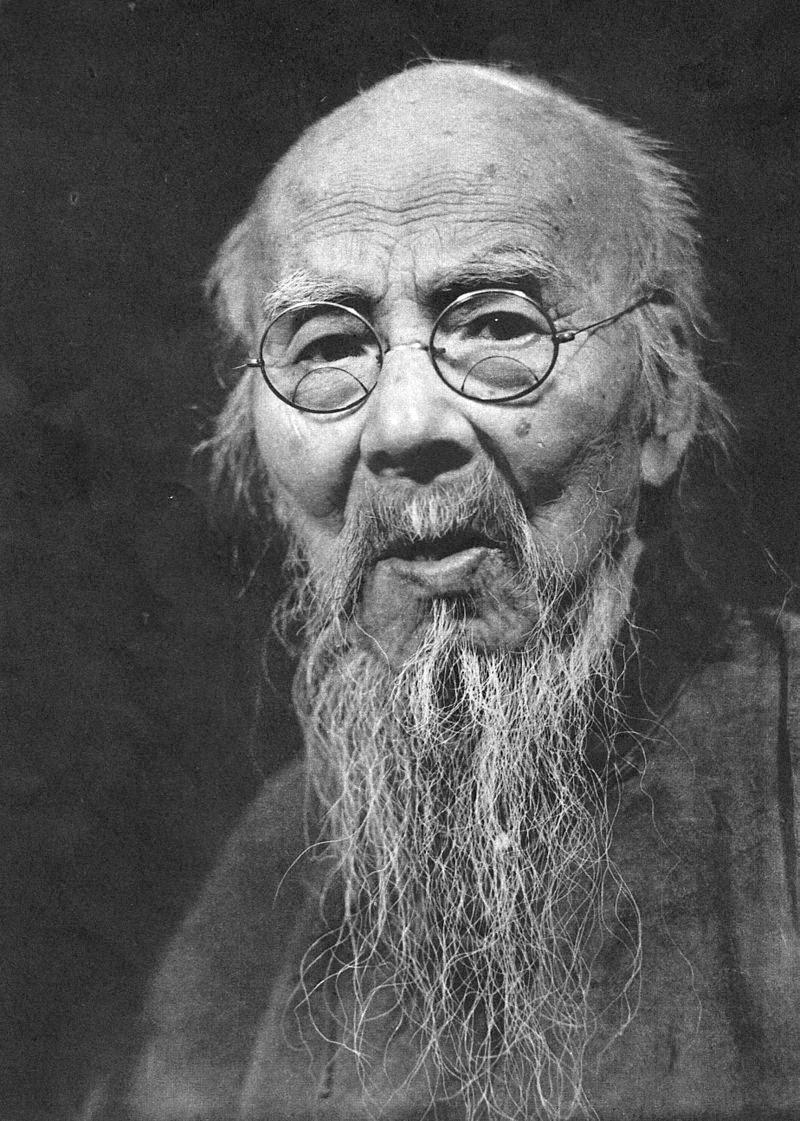

This week's edition of Chinese Lives looks at Qí Báishí 齐白石, “the Picasso of China.”

Chinese Lives is a weekly series that looks at notable figures from all eras of Chinese history.

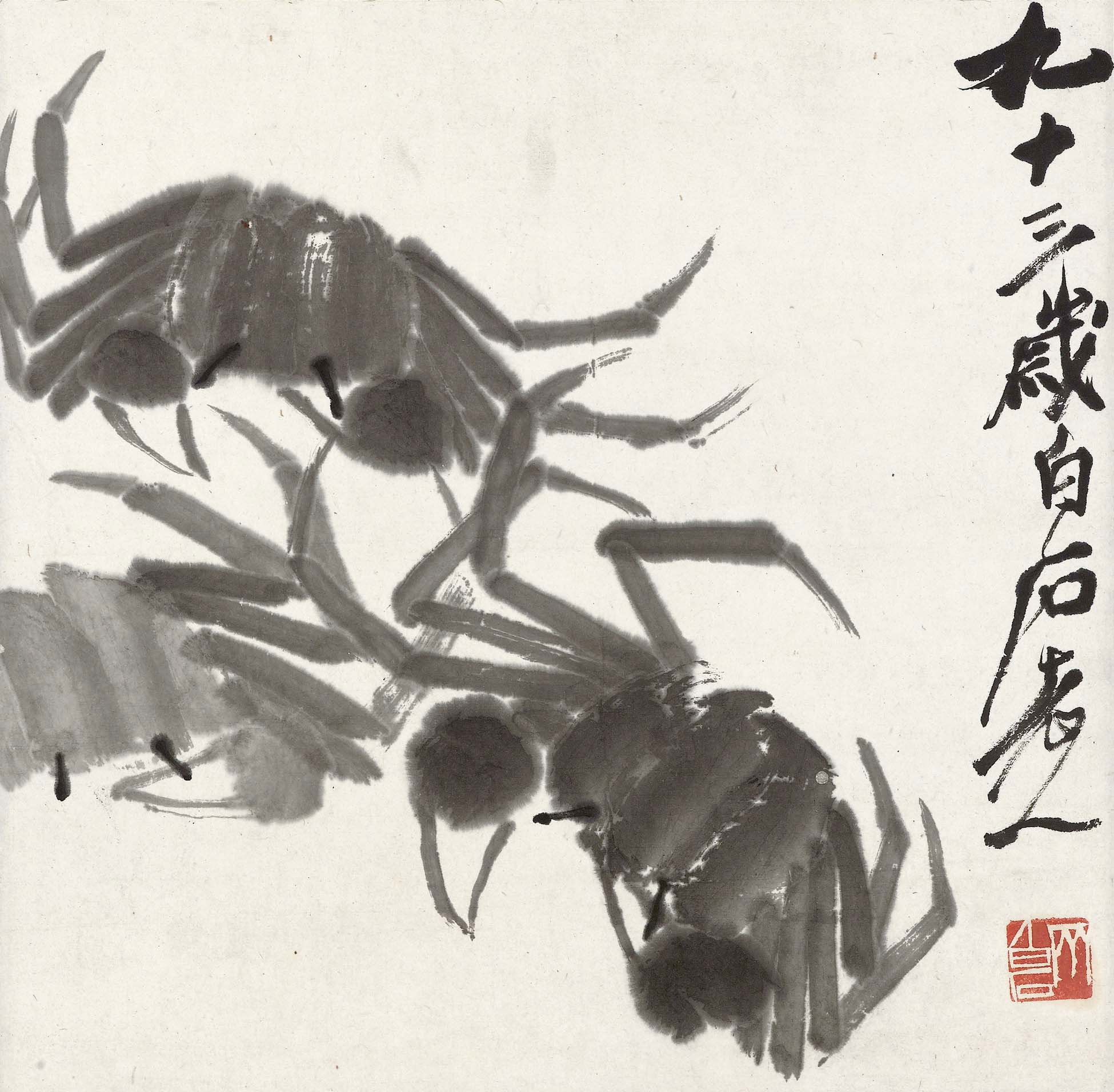

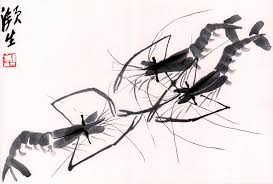

Qí Báishí 齐白石, “the Picasso of China,” is famous for shrimp. Lots of them. He painted picture after picture of these crustaceans in his old age, symbols of the joys of a childhood spent playing by a pond filled with them in his native Hunan. Don’t be fooled by their simplicity. He observed them for hours in a shallow blue bowl on his desk, capturing their essence with a few quick strokes of his pen, over-painting in varying shades of black ink to recreate their transparent bodies. No artist has ever made these spindly, uninspiring, ordinary little creatures feel so alive, so characterful, and so remarkable.

This came after decades of ceaseless practice and innovation, a lifetime’s struggle up the career ladder in which he began as a humble carpenter and ended with the CCP accolade of the Chinese People’s Most Distinguished Artist. His paintings have broken records at auction — in 2010, 53 years after his death, he became the second highest-selling artist in the world, wedged between Picasso and Warhol. Picasso called him “the greatest Oriental painter,” admiring how he “paints fish with colorless ink, but still can make people see the stream and fish swimming.” The Spaniard didn’t dare visit China — “for you have a Qi Baishi.” Although the two artists never met, they shared subject matter in their work, like the dove of peace after World War II.

Who is Qi Baishi?

Qi Baishi was a man of humble origins who painted humble things, who breathed new life into traditional Chinese painting, his artwork hailed by Communist revolutionaries and still taught in Chinese schools today.

Born at the end of the Taiping Rebellion in 1864, Qi didn’t seem destined for much. He was the sickly son of poor peasants, and withdrew from school after two years due to ill health. But he had a plan. At 18 he found an early-Qing drawing book, The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, and learned how to paint and draw flowers, animals and people. Working up from a carpenter’s apprentice, Qi found himself developing an all-consuming drive to become a master of high art.

This was the Literati art tradition, which blended landscape painting, music, poetry, and calligraphy. It had inspired the European Impressionists with its belief that capturing the essence of the thing is more important than being true to reality. A few simple brushstrokes were enough to convey any animal, vegetable, or mineral. Qi found skilled mentors for everything he needed to learn. With training, he slowly established his career as an artist while also making a name for himself with his furniture and carving ink-stone seals (used by the rich instead of a signature).

But it wasn’t enough. In 1902, not content with his work, Qi left Hunan and wandered all over China searching for inspiration, visiting famous beauty spots and learning from prominent artists. By the time he settled down in Beijing in 1919 he was in his 50s, with a wealth of experience and material, now a master of xiěyì 写意 painting (the artist trying to catch the essence of a subject in a quick freehand sketch that need not be true to life) and a follower of the late Qing’s “Yangzhou School” of painting (a branch of Literati that painted more everyday scenes with eccentric brushwork and brighter colors).

But Qi lived a life of abject poverty, relying on the hospitality of monks while he tried to make ends meet. He went unnoticed until a chance encounter with Beijing’s foremost art theorist Chén Shīzéng 陈师曾. Chen was a teacher of traditional Chinese painting, dedicated to the defense of Literati style, under siege by modernizers who demanded heightened realism or oil painting, as in Europe. But, he argued, European modernist painters now favored art that had done away with realism in the same way Literati painting had centuries before. The seeds of Expressionism or Futurism could be found in traditional Chinese painting. For once, China was ahead of the curve.

Chen was struck by Qi’s seals, laid out on display in a Beijing art shop. They were simple and highly distinctive; a unique, spidery script that wouldn’t have looked out of place amongst the Viennese Secessionists of the 1900s.

Chen urged Qi to transfer this style to his paintings, marking the start of what Qi called his “twilight year reforms.” His painting became freer and looser, Chen submitting samples of Qi’s work for exhibition in Japan in 1922. Not only did they all sell, but two found their way into museums in Paris. International fame earned him great respect in China, and he was finally offered a post at the Beijing Arts Academy in 1927, despite having no formal artistic education whatsoever.

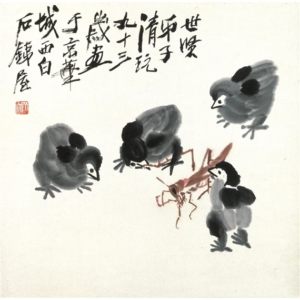

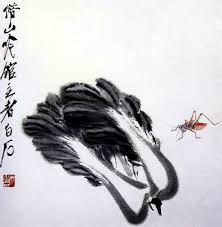

His simplicity revolutionized Literati painting. Whereas many conservatives painted elaborate scenery wreathed with mist or mountains, as had been done for generations, rich in detail and perfectly balanced, Qi found beauty in the mundane and the minimal. Chicks toying with a grasshopper perhaps…

…or the aimless wanderings of crabs…

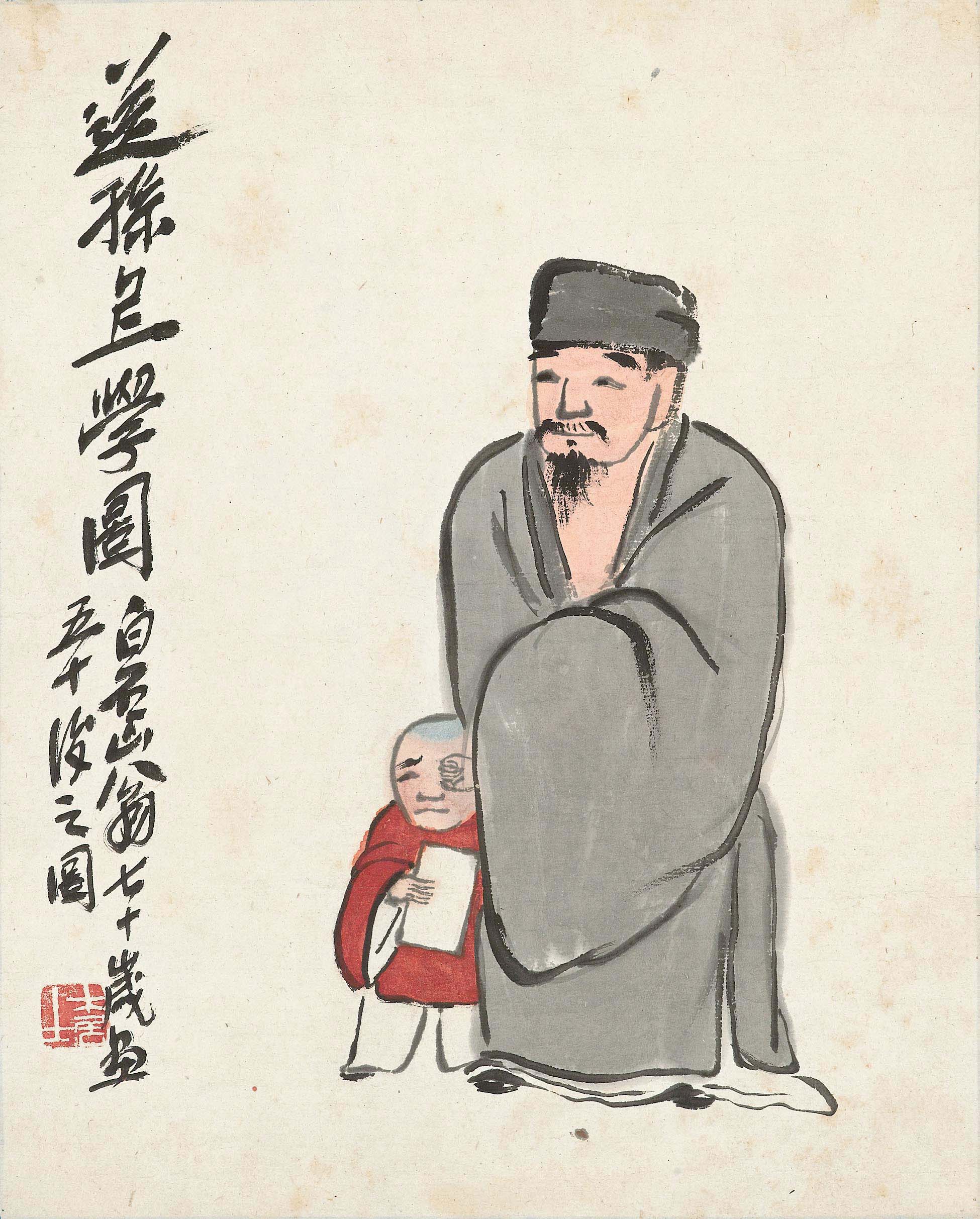

…a boy being frogmarched to school (based on his own experiences with one of his many grandsons)…

…or freshly uprooted cabbages:

Qi gave other works splashes of bright color, varying the usual darker tones favored by traditional masters. His brushstrokes were loose but complex, giving less detail but enough to keep the content realistic and textured.

Innovation was never the strong point of traditional Chinese painting, but Qi Baishi was determined to create a style that was uniquely his own. “When I cut seals I do not abide by the old rules, and so I am accused of unorthodoxy,” he wrote in his journal. ‘But I pity this generation’s stupidity, for they do not seem to realize that Qin and Han artists were human and so are we….I suppose future generations will admire our present artists just as much as we admire these men of old. What a pity that I will not be there to see it!”

His unorthodoxy, combined with a peasant background and lack of education, were all formidable obstacles in his long battle for recognition in Beijing art circles. But fame eased prejudices, and helped him establish a middle ground between modernizers and traditionalists. In his old age, Qi became a renowned and prolific painter, creating five to six paintings a day from the age of 75 to 88. He is said to have created over 600 in 1953 alone. During this period he was also a prolific poet, publishing two books of verse and leaving behind 3,000 poems by the end of his life.

Such a large output means his pieces can still be found at auction selling for around a hundred thousand U.S. dollars. The gradual encroachment of Chinese collectors into the international art market has driven prices up, buyers eager to have their own work from one of China’s greatest modern artists. In 2017 one of his works fetched $140.8 million at auction.

Despite earning very good money for his work during his lifetime, Qi preferred to live frugally. “It’s enough for me to have bread and a fireplace when I’m hungry and cold. Why should I have to fight desperately for that much money?’ Having a very large family to feed (with more than 40 grandchildren in the last decade of his life) could hardly have helped.

Good thing he was a patriot. He’d been advised in the 1920s to set up shop in Japan and take advantage of his popularity there, but he stayed in Beijing. During the Japanese occupation, he put up a sign saying he would not be selling any pictures to officials or collaborators. He stayed out of domestic politics, but still presented one of his works to Chiang Kai-Shek (Jiǎng Jièshí 蒋介石) in 1946. During the Korean War, he campaigned on behalf of anti-American charities to help North Korea.

He also became a poster boy for the CCP, earning visits from Zhōu Ēnlái 周恩来 and audiences with Mao. His humble roots, along with his down-to-earth subject matter and popularity, earned him favor with the Party, which declared him in tune with the artistic needs of the people and made him a deputy of the National People’s Congress (China’s legislative branch of government). In 1953, he was even made president of the China Artists Association. A revolutionary government favoring a wizened old artist was their way of balancing change and tradition in the same way Qi had. He died in 1957 aged 93, spared the destruction of the Cultural Revolution.

Qi Baishi is a strange character, one of the few in China’s turbulent 20th century who looked to the country’s homegrown heritage for fresh ideas and updates, rather than imported Western values. At a time when China is now striving to recover an identity beyond the ideologies of Karl Marx and Adam Smith, perhaps Qi Baishi can be a source of pride: proof that it’s possible for the old ways to hold their own in the modern world, a source of admiration both at home and abroad. Not bad for a man who stared at shrimps.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series. Previously: