Sometimes the ancients knew best. In 2015, Chinese doctor Tú Yōuyōu 屠呦呦 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for her research on Artemisinin, a drug drastically reducing the death toll for malaria. By 2005, the World Health Organization was advocating Artemisinin-based therapies as its primary anti-malaria treatment, thanks to Tu’s discovery.

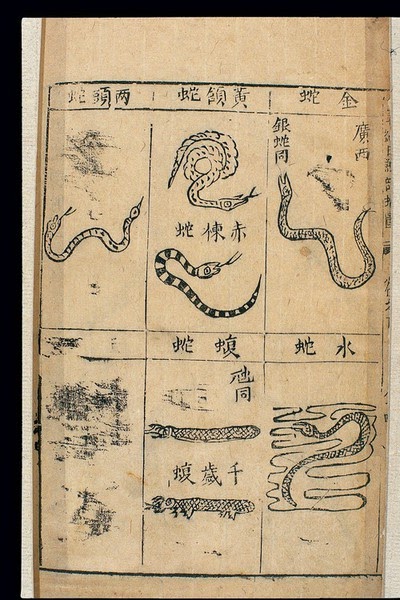

Or should that be “re-discovery”? The plant the drug is extracted from is prescribed as a tea to treat chills and fevers from malaria in a giant tome from the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). This was the monolithic Compendium of Materia Medica (本草綱目 běncǎo gāngmù), its pages crammed with nearly 2,000 ingredients for over 11,000 different medicines, an unparalleled reference point, the standard encyclopedia for traditional remedies in China up to 1959.

It was the life’s work of a colossal name in Chinese science, whose face is found on hospital walls and in school textbooks — the physician Lǐ Shízhēn 李时珍.

Who is Li Shizhen?

Although born into a family of doctors in what is now Hubei Province in 1518, Li’s father set him to work studying for the imperial exams to elevate the family. He failed the provincial level (the “Juren”) three times. He became a physician instead.

Initially apprenticed to his father, Li’s climb was swift. He served in the court of a minor member of the Imperial family in Hubei, then recommended to the prestigious Imperial Medical Institute in Beijing. But he was only there for a year, suddenly returning to work in the provinces.

That could have been the last history heard of him, had it not been for his magnum opus. Most běncǎo 本草 — catalogues listing medicinal ingredients and their properties — were collated by a team on the Emperor’s orders. But Li spent around 27 years creating one that was longer, more accurate, and more authoritative than anything that had gone before. Entirely on his own.

Herbal remedies are integral to Chinese medicine, which theorizes that the body is not outside and above nature, but an ever changing organism swayed by the outside world, in need of constant nurturing. Traditional medicines seek to balance conflicting forces in the body and boost health.

The difference between Western and Chinese medics has been likened to that of a “mechanic” and a “gardener”, in Harriet Beinfield and Efrem Korngold’s influential book on the subject. While Western medicine seeks to fix a problem once a disease has started, Chinese medicines are more indirect, pre-emptive strikes against illness by pruning and moulding nature into a healthy shape, preventing the conditions that allow disease to flourish in the first place.

Chinese medicine and meals are seamlessly interwoven, tending to a person’s health as part of daily food or drink. For example the white fungus tremella fuciformis, a key ingredient in snow fungus soup, has been the subject of studies demonstrating it can reduce cholesterol.

Li didn’t discriminate in his choice of ingredients. The natural world was a magnanimous bounty, everything within it having some sort of use. You just had to find out what it was. Li heard about turtle sperm from a traveller, yet it was impossible to get hold of samples to experiment with. But perhaps someone would one day, so into the compendium it went.

As a result, the book bears all the hallmarks (good and bad) of an open medical mind. Dragon bones sit alongside cockroaches, pepper next to almonds, pumpkins or sweet potatoes (imported from across the world). It includes widely accepted panaceas like ginseng root, chamomile, and marijuana but also substances at the heart of modern-day controversies like rhino horn and donkey-hide gelatin, and even human blood or nail clippings (man was, after all, a part of the natural world — but Li stopped short of human flesh).

They sit in lists of descriptions and uses, Li consulting sources earlier Ming doctors had rarely bothered to consult: travellers, peasants, fishermen, and so on. Clearly, Li had been investigating ingredients for himself alongside the 900 books he claimed to have read for the work.

Published posthumously in the 1590s, editions of the work were reprinted and spread widely until it was lauded throughout China. He had collated knowledge scattered across hundreds of volumes (the recipe that aided Tu Youyou was already over 1000 years old by the time Li recorded it) and corrected many critical errors (including the use of mercury for longer life, or arsenic as a cleaning product). It became essential reading. But it wasn’t perfect — indeed, it was a victim of its own success, so voluminous that no physician could possibly absorb its contents by heart.

Li’s Compendium of Materia Medica was a cornerstone in the development of TCM in China after the Communist Party took power in 1949. In that year, China had around 40,000 doctors Western- and Soviet trained doctors serving a population of 540 million. By comparison, in 1949 the United States had over 200,000 doctors in a population of 149 million.

To plug medical demand, the government promoted “barefoot doctors”: These were peasant farmers who received basic training in infectious disease prevention, first aid, and a range of basic medicines and treatments, both Western and traditional Chinese. One speciality of barefoot doctors was their use of easily accessible herbs and roots growing in the countryside. For many years, barefoot doctors provided the only health care services available to large swathes of rural China.

Li became known as a model barefoot doctor, idealised in speeches and on the silver screen as a man who had given up his high-flying career to serve the common folk, creating his book out of love for them, braving harsh mountainous terrains on the hunt for rare specimens. In a speech in 1965, Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 portrayed Li as a doctor who had learned through experience rather than academic study, despite a long tradition that he had spent a decade indoors researching for the book.

TCM is fiercely defended by many in China, and is a source of national pride and cultural identity. Li Shizhen’s book is a symbol of that pride, a reminder of how extensive and wide-ranging Chinese medical investigation had become by the 16th century. Not for nothing has the Compendium of Materia Medica been included in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register, or graced the title of a song by Jay Chou (周杰伦 Zhōu Jiélún) celebrating TCM.

Although there are new official pharmacopoeias in TCM, Li’s book is still a valuable point of reference for practitioners hunting for more obscure remedies. Scientists are still testing the recipes he recorded, determined to convert more practices from TCM into effective modern medicine. But success stories like Tu Youyou and Artemisinin are — so far — the exception rather than the rule.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series. Previously: