How will Manhattan’s Chinatown emerge from its worst five months ever?

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, New York City’s Asian American communities have suffered particularly hard. As New York slowly emerges from a months-long lockdown, we take a look at some of the groups fighting to save Chinatown.

For months, New York City’s lockdown order has brought uncomfortable quiet to the streets of Manhattan’s Chinatown. The lockdown darkened the neighborhood’s storefronts and shuttered restaurants. While the city is taking its first baby steps out of that lockdown and many stores have recently begun to reopen for takeout, the neighborhood’s usual animation has been dampened by the months of uncertainty, with some stores closing permanently, unable to survive the long period of halted business.

All non-essential business in New York was officially put on pause on March 20. Chinatown, a uniquely dense neighborhood boasting over 270 restaurants, over 100 gift shops, and a handful of senior centers all within one square mile, saw a particularly drastic change. Chinatown restaurants, known for cheap meals and fast turnovers, are barely scraping by on takeout, while most senior centers have transitioned operations to delivering food to homebound elderly. The 27.3% living under the poverty line in Chinatown (compared with the 17.9% citywide in 2017) are also hurting as unemployment has skyrocketed. Rising anti-Asian sentiment has deflated the confidence of many, regardless of age or creed.

Although New York State’s first COVID-19 case wasn’t confirmed until March 1, Chinatown and Asian businesses across the city took a nosedive starting in early January, as China slowly revealed more information to the World Health Organization of a mysterious new pathogen in Wuhan, later identified as a highly infectious new coronavirus. As coronavirus panic spread, so, too, did xenophobia. Conspiracies claiming that the respiratory disease originated from a woman eating “bat soup” in Wuhan gained significant traction online, and although this was later disproved, people were already starting to avoid Chinatown and all things Chinese. At the same time, reports of coronavirus-fueled attacks against Asian Americans increased in New York, causing widespread anxiety among Asian New Yorkers. Along with the rising xenophobia, bilateral relations between the U.S. and China also worsened, with some in Washington introducing legislation that would allow Americans to sue China for damages caused by the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, U.S. mistrust of China rose to record highs around this time. Amid all of this, Chinatown business trickled to an alarming standstill.

The combination of a state-mandated lockdown and rising anti-Asian sentiment has left Chinatown in crisis. More so than most other neighborhoods, Chinatown depends on foot traffic to stay afloat: tour groups, hungry locals, early-morning elderly grocery shoppers, and the clamoring afternoon dim sum rush. Without this continuous stream of people, the neighborhood loses its economic lifeline. In light of this, some residents have mobilized in response to the neighborhood’s newfound challenges.

“In some ways, this is the perfect storm of worst-case scenarios for Chinatown,” says Jennifer Tam, co-founder of Welcome to Chinatown. Jennifer, along with her friend Victoria Lee, started the grassroots initiative after this year’s Lunar New Year celebrations turned out to be uncharacteristically quiet. “Nobody was here. It was like half the crowd size, and usually it’s packed shoulder to shoulder,” Tam recalls. Many restaurants reported losing 50-70% of their regular business during this time, and the drain has only continued.

With no clear solution, Tam and Lee came up with a multi-pronged approach to address the issues facing Chinatown’s restaurants. First, through a donation campaign, Welcome to Chinatown uses crowdsourced funds to purchase meals from Chinatown restaurants to send to healthcare workers around NYC. It’s an effective strategy, giving donors the ability to support two causes with one donation. Then, as the city has begun its phased reopening, Welcome to Chinatown has shifted its fundraising focus toward small business relief funds for the neighborhood, which has largely been neglected by national COVID-19 relief programs.

The initiative also supports restaurants, many of which are offline and cash-only, in becoming “future-proof,” addressing lasting commercial barriers, and offering resources needed to build a more sustainable business model. With its team of volunteers, Welcome to Chinatown is working to design websites and set up gift card programs, and, as of June 17, has raised over $210,000 to go toward Chinatown restaurants and NYC healthcare workers.

Fighting a similar fight is 46 Mott Street, a bakery and grocery store settled at the southern point of one of Chinatown’s busiest streets. The shop’s manager, Patrick Mock, says that while 46 Mott Street saw a dramatic drop in business starting in January after general panic emerged over the virus, the anxiety sweeping through his community was just as bad. “People seem to think that anything Chinese was related to the virus,” he tells me over the phone while delivering meals to a nearby hospital.

Like many other business owners in Chinatown, Mock is anxious over the weight of that burden. “Rent is a big headache for small business owners right now,” he says. But even so, the manager has found a way to support the members of the neighborhood. Starting in April, 46 Mott Street began providing 150 free meals each day to anyone in need, and has been offering front-line workers complimentary coffee and herbal tea. Each morning, his shop has a long line of people wrapped around the block, all standing six feet apart. Many of the people waiting on line are elderly residents who have found difficulty accessing groceries after the neighborhood’s stores shut. While he chalks up the effort as a small gesture, Mock also acknowledges that it’s the best way he can give back to his community.

A few blocks away is Heart of Dinner, a relief group aimed at supporting Chinatown’s elderly and homebound residents. Founded by restaurateur Moonlynn Tsai and actor Yin Chang, Heart of Dinner uses the spacious kitchen of Kopitiam, a local Malaysian restaurant co-owned by Tsai, to provide hot, low-sodium meals to the neighborhood’s elders. As one in four Asian seniors in New York lives in poverty, the free, warm, and delivered lunch boxes provide a small piece of economic relief through food. The group has also been sending along handwritten notes, crowdsourced from dozens of local volunteers, to accompany the meals. Written in both Chinese and English, oftentimes on delicate origami paper, the notes remind seniors, “We are thinking about you” and “We love you.” As senior centers have closed and a portion of home health aides have been furloughed, many elders have also been battling isolation and depression, and the notes offer a much-needed sense of intimacy. Since April, the group has raised over $80,000.

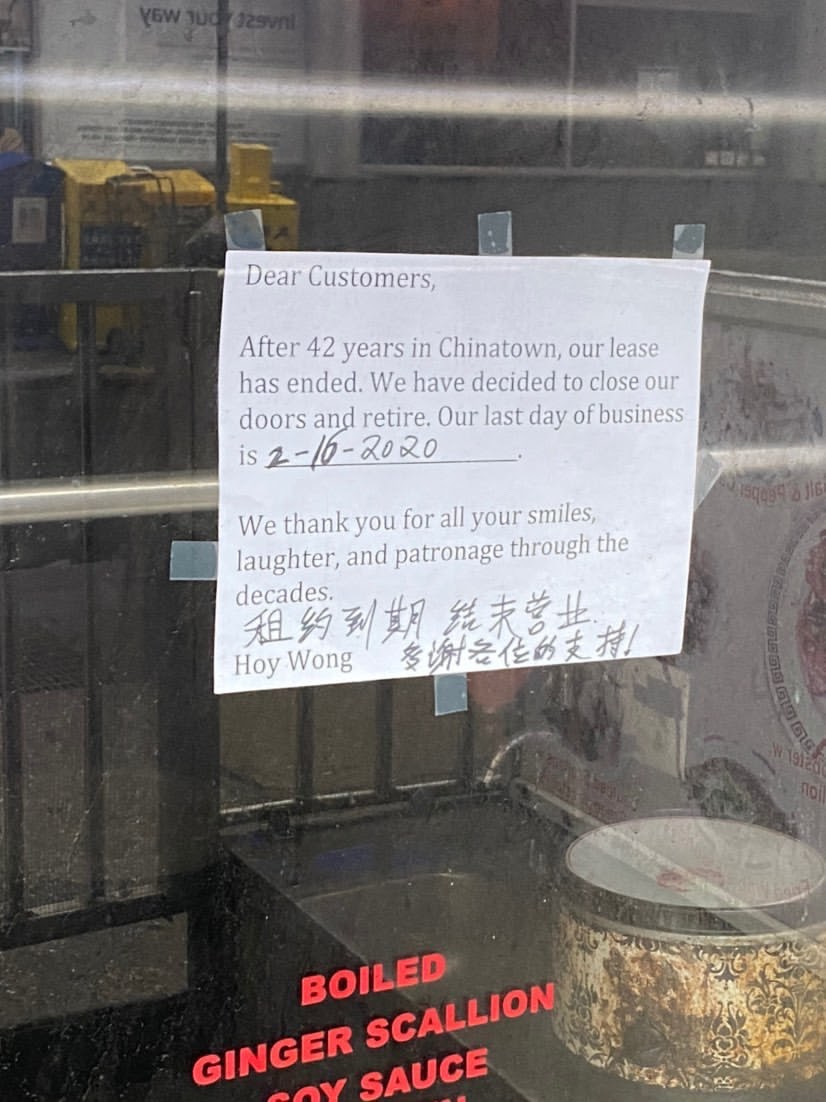

The past five months have been some of the hardest in Chinatown’s history. Even after the 2008 financial crisis, which decimated tourism and the food industry, people still had the urge and ability to eat out in Chinatown. With the coronavirus, prejudice and a lockdown order have all but upended Chinatown’s entire business model. The heartbreak of the neighborhood is visible in handwritten signs pasted on shop front windows, with messages announcing indefinite pauses or permanent closures: “After 42 years…we have decided to close our doors and retire.”

In NYC’s phased reopening plan, restaurants and retail shops are set to open in Phase 3. While that is soon approaching, it will take a lot more than a slow return to normal for the neighborhood to regain its losses, making the grassroots efforts of the neighborhood all the more important. “Chinatown is practically on life support,” Patrick Mock tells me as he parks his car, getting ready to drop off his delivery. “I’ve always wanted to give back — to give back to the community that took care of me. You have to start somewhere.”