A fresh look at the 1930s Jewish refuge, in ‘The Last Kings of Shanghai’

Jonathan Kaufman’s latest book provides an engaging, colorful history of Shanghai’s past that fully explores, but does not romanticize, the cosmopolitanism and colonialism of that era.

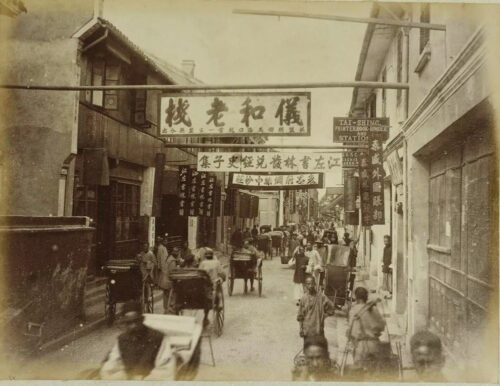

When I was living in Shanghai in the mid-2010s, two very different landmarks became constant tour stops as I played guide to visiting friends and family: the 1920s throwback Fairmont Peace Hotel, and the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum, housed in an old synagogue in Shanghai’s Hongkou District, once known as the Shanghai Ghetto. Jonathan Kaufman’s latest book, The Last Kings of Shanghai, provides an engaging history of how the iconic hotel and the Shanghai Ghetto came to be.

Kaufman traces the interconnected histories of two entrepreneurial families: the Sassoons, once known, due to their wealth and influence, as “the Rothschilds of Asia” — a term Kaufman notes the Sassoons themselves considered somewhat of an insult, since the Rothschilds were mere nouveau riche — and the Kadoories, depicted as the Sassoons’ less connected but determined distant cousins.

Forced to flee a Baghdad that was increasingly hostile to Jews in the late 1820s, the Sassoons moved their business empire to British India. The Kadoories would eventually follow suit, hoping to gain employment from their distant relatives. Their respective pursuits of fortune and opportunity would eventually take branches of both families to Shanghai, a port city increasingly controlled by foreign powers desperate for access to trade with China.

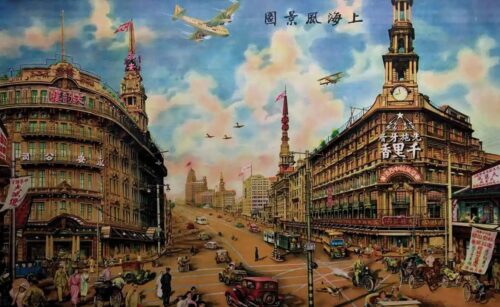

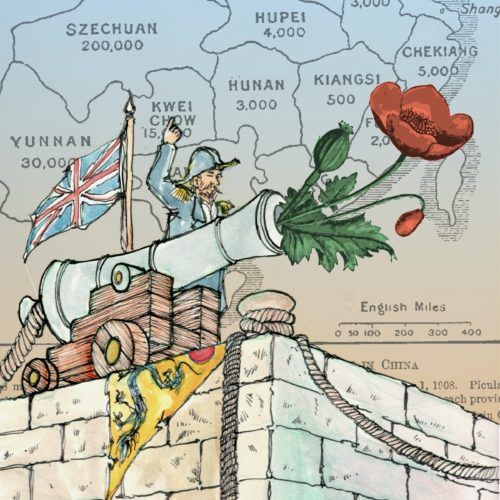

With their direct links to opium production in India, the Sassoons were quick to find success in China by securing a monopoly on the country’s opium trade. While Britain’s agreement to curb and eventually cease Indian opium exports to China in 1907 dealt the Sassoons a solid blow, the family’s investments across textiles, ports, banking, and perhaps most notably, Victor Sassoon’s investments in Shanghai real estate, including the Cathay Hotel (now the Fairmont Peace Hotel), solidified their place among the world’s elite.

While wealth initially proved more elusive for Elly Kadoorie, who began apprenticing for the Sassoons as a 15-year-old in India and later in Hong Kong, the family would also come to amass a fortune. After cutting his teeth in the rubber stock trade, Elly established himself as a successful financier, made key investments in Hong Kong electricity company China Light and Power, and, along with his two sons, built luxury hotels and properties in Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Shanghai cosmopolitanism reexamined

Writers, both Chinese and foreign, have tended to either romanticize Shanghai’s past for its glamor and cosmopolitanism or emphasize the violent colonial scramble for access to Chinese markets that saw Chinese denigrated to second-class citizens on their own soil. Kaufman manages to straddle both sides of the colonial-cosmopolitan coin, and, in doing so, illustrates how complicated the figures that shape history can be.

While Kaufman details the glitzy parties that brought together people from various nationalities hosted in the Cathay and the Kadoorie’s Majestic, he also notes from the beginning that both families, despite living in Shanghai across generations, remained grossly out of touch with the rest of Chinese society and were, in many ways, agents of British imperialism. Kaufman details the tactics the Sassoons employed to outcompete rivals in the opium trade, which wreaked havoc on the lives of many ordinary Chinese, and points out that while the Sassoons were well aware of the perils of opium, their actions never seemed to weigh on their moral conscience, or indeed prompt any self-reflection whatsoever. Even supposedly progressive members of the family, such as Rachel Sassoon Beer, who became the first female editor-in-chief of a British newspaper, took pains to defend the family’s role in the trade generations later.

Similarly, Kaufman shows how both families’ luxurious hotels not only contributed to the physical Westernization of Shanghai’s landscape, but also stoked resentment among the local population over the increasing inequality between Chinese and foreigners. In one brief but powerful scene, Lǔ Xùn 鲁迅, now considered perhaps the founding figure of Chinese modern literature, was forced to walk up seven floors of the Cathay Hotel to visit a British friend after being ignored by the elevator operator. And while this resentment and the subsequent communist movement would ultimately lead to the demise of both families’ Shanghai fortunes and the end of their time on the mainland, Kaufman avoids giving it his full attention. In fact, Chinese citizens only appear in the book as peripheral characters, something Kaufman acknowledges in the preface and justifies on the basis that this itself reflects just how removed these families were from their Chinese peers.

Yet while Kaufman never attempts to downplay his subjects’ colonial legacies, he complicates them by focusing on both families through the lens of their Jewishness, a theme that Kaufman has covered extensively over the years. Although the two families came to be incredibly wealthy and forged intimate ties with those occupying the highest echelons of British society, in the context of rising anti-Semitism, their Jewishness prevented them from perhaps ever truly belonging to it (and in many ways, there is an unusual subalternness to these otherwise wealthy elites — the two families never really appear to wholly belong anywhere). In fact, despite having a British wife and children, Elly Kadoorie was repeatedly barred from acquiring British citizenship and, for a long stretch of time, was effectively stateless. The Kadoories would spend the last years of Elly’s life imprisoned by the Japanese in Shanghai’s Chapei internment camp.

The families that made Shanghai a Jewish refuge

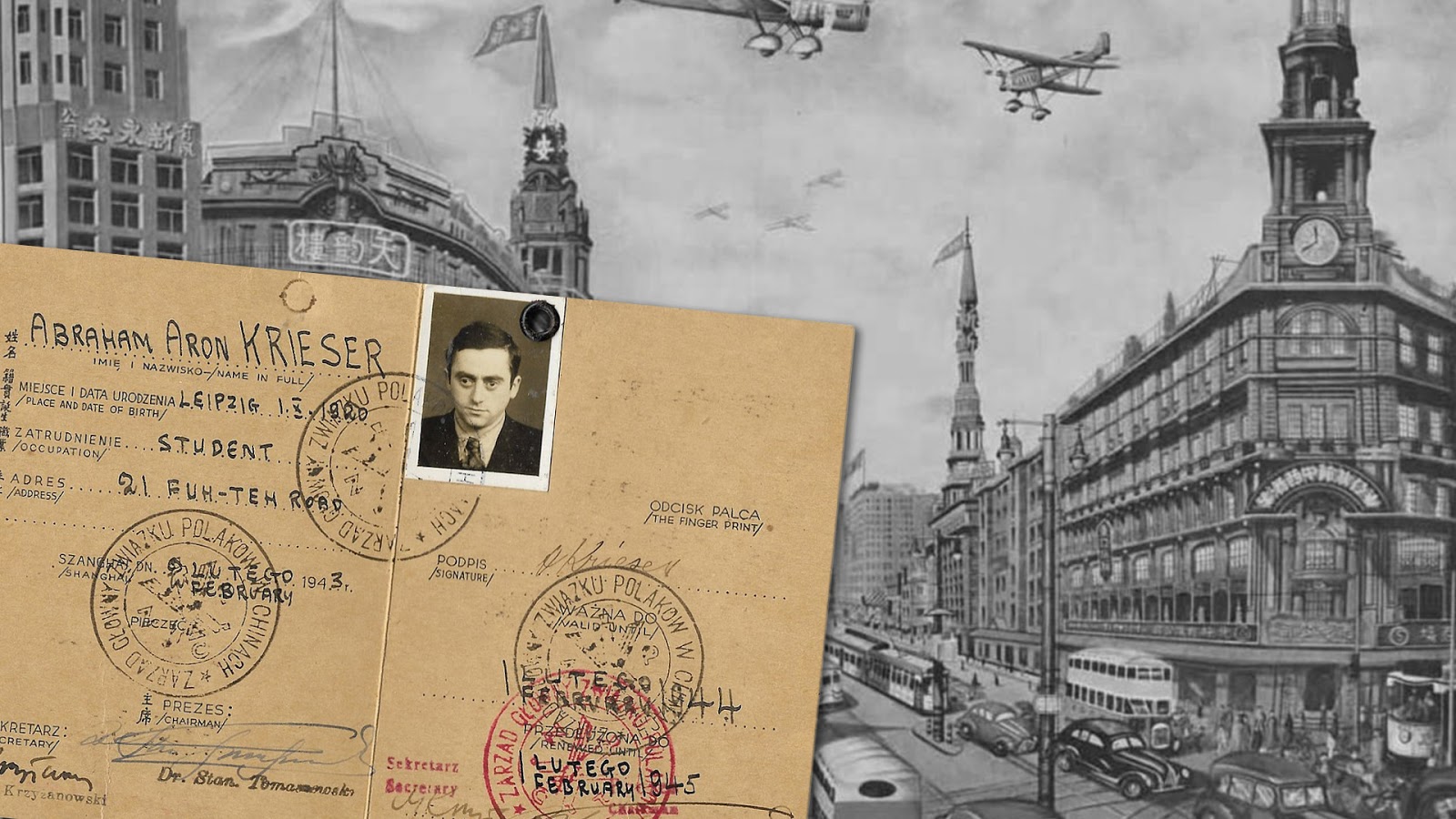

What really grants the two families a degree of redemption, and forms the most engaging part of the book, is the story of how both Sassoons and Kadoories played key roles in establishing Shanghai as a temporary refuge for some 18,000 Jews fleeing Europe.

Kaufman depicts how despite their rival hotel empires, the Sassoons and the Kadoories worked together to convince the Nazi-aligned Japanese authorities, who controlled much of the city, not to expel the new arrivals, who at this point were arriving in the hundreds every week, and to treat them on a par with the city’s other foreign nationals. Victor Sassoon, Elly Kadoorie, and his son, Horace, provided housing, schooling, and food to refugee families, with Victor opening up one of his luxury skyscrapers to serve as a reception center for new arrivals while a kitchen in the building’s basement provided them with thousands of meals each day, and rallied high-profile Chinese intellectuals and politicians to protest the German government’s anti-Jewish policies. One family even recalled spotting a German sign as their boat arrived in Shanghai that read: “Welcome to Shanghai. You are no longer Jews but citizens of the world. All Shanghai welcomes you.”

While this is not the first book to provide a detailed portrayal of the Shanghai Jews, it is likely the most accessible. Like any respectable history written for a general readership, Kaufman ensures his readers’ attention by neatly weaving in salacious asides about playboy hotelier Victor Sassoon’s sex life and family factional infighting as he traverses generations of history.

Similarly, Kaufman steers clear of the impulse of many English-language accounts of Chinese history to provide any sort of grand diplomatic narrative. Instead, he paints an accessible character-driven story of the people who played a role in the creation of modern Shanghai, and how broader political developments in turn shaped their own fate.

Kaufman observes that up until the 1980s, the history of these Shanghai dynasty families and their rampant capitalism had been largely erased from official narratives in China.

In an effort to legitimize the return to market capitalism, and as former Shanghai refugees gained international prominence and sparked a mini tourism industry around the former settlement area, this history has proudly regained its place in the official narrative, albeit with the notable ommission of the role that Japanese officials played in allowing Shanghai’s intake of refugees in defiance of their Nazi allies.

As global political tensions flare and the coronavirus exacerbates underlying racial tensions in China and much of the rest of the world, one is left wondering how, and for what purposes, the history of the Shanghai Jews will be told in the future.

The Last Kings of Shanghai is out now through Viking Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.