This Week in China’s History: July 15, 1907

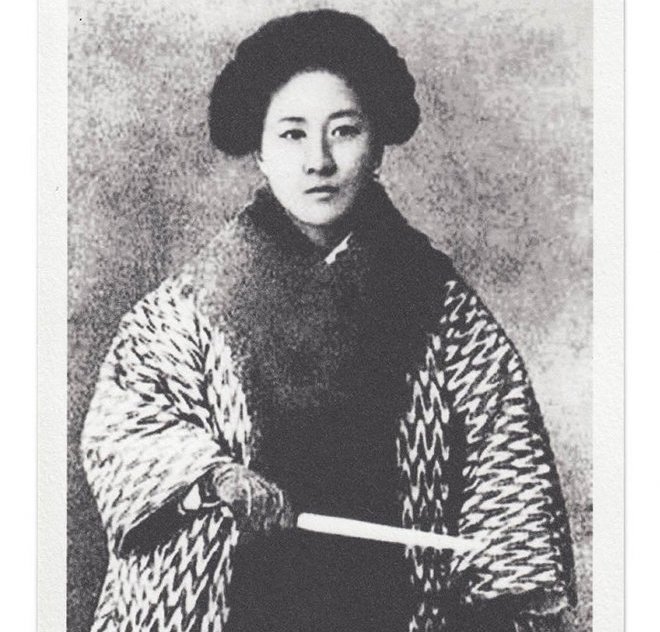

A revolutionary, educator, poet, and feminist, Qiū Jǐn 秋瑾 was executed in the city of Shaoxing, near the head of Hangzhou Bay, by Qing imperial soldiers on July 15, 1907. She had been convicted of conspiring to assassinate Qing officials with the goal of overthrowing the dynasty that had ruled China since 1644.

Refusing to confess to her alleged crimes, Qiu Jin instead presented her interrogator with lines of poetry:

Autumn winds

Autumn rains

Rend one’s soul.

The lines — from a poem by Táo Zōngliàng 陶宗亮, as translated by Eileen Chengyin Chow — were especially evocative because the character “Autumn” repeated in the poem’s first two couplets was Qiu Jin’s surname, and because Chinese poetry commonly associated autumn with death and mourning. The lines have come to be her epigraph, punctuating a bold, short, singular life.

She was born in the subtropical port city of Xiamen in 1875 (some sources say 1877). Hers was an affluent family, with both parents from elite families; her father was a government official. Had she been born a boy, Qiu Jin would have studied for the same civil service exams that had led Hóng Xiùquán 洪秀全 — the founder of the Taiping movement — to grief. Instead, her gender forced her to a different path.

To begin with, her feet were bound, a custom with origins some 1,000 years before Qiu was born. Her mother would have begun tightly wrapping Qiu Jin’s feet in strips of cloth when she was around six years old, if standard practice was followed. The bindings prevented the feet from growing normally, instead curling the toes underneath, breaking bones in the process and pressing the bottoms of the toes against the sole of the foot. The big toe was left unbound, leaving the young girl to learn to walk on the knuckles of her toes, with only the big toe for balance. The agonizing years-long process greatly limited mobility, though research by Dorothy Ko and others has shown that women with bound feet were in fact quite mobile, going so far as to suggest that women gained social capital from the practice.

Feet bound, married by arrangement into a merchant family, and soon with two children, Qiu Jin seemed a model of a traditional Chinese wife until 1903, when her husband gained a government position in Beijing. The family moved to the metropolis and everything changed. As Amy Qin wrote in a century-belated New York Times obituary, “For Qiu, life in the imperial capital was decidedly less dull. She struck up friendships with like-minded women and began to take an interest in China’s political affairs. She unbound her feet, drank copious amounts of wine and began experimenting with cross-dressing and swordplay.”

The changes were risky, not to mention painful. Learning to walk on unbound feet may have been even more agonizing than the initial binding process, and the new social scene was worlds away from the traditions that had structured her life in the south. Qiu Jin, however, was eager to participate in a China in ferment. Ideologies and ideas from abroad were encountering a society that was on the cusp of revolutionary change.

Many of the ideas that shaped China at the time arrived via Japan, which was itself grappling with European expansion and imperialism. Increasing numbers of Chinese students and intellectuals began traveling abroad in the late 19th century, and Japan, many thousands of miles closer than Europe or America, was a natural choice. By the early 20th century, thousands of Chinese students went to Japan each year. In the summer of 1904, Qiu Jin became one of them.

Qiu Jin didn’t just go to Japan to study, which would have been bold enough; she embarked on new life, a decision she reflected on in poetry, translated by Jonathan Spence in his history of China’s literary revolution, The Gate of Heavenly Peace:

Sun and moon have no light left, earth is dark;

Our women’s world is sunk so deep, who can help us?

Jewelry sold to pay for this trip across the seas,

Cut off from my family I leave my native land.

Unbinding my feet I clean out a thousand years of poison,

With heated heart arouse all women’s spirits.

Leaving behind her husband and children, Qiu Jin began a new life as an activist. Japan was a base for Chinese reformers and revolutionaries, especially after many of those involved in the failed 100 Days of 1898 had escaped there. Qiu Jin quickly became a leader among the Chinese community. In December of 1905, none other than Lǔ Xùn 鲁迅, who would become China’s most famous writer, was in the audience as she delivered a fiery speech to Chinese students. Eileen Cheng described the scene as a defiant Qiu Jin insisted that it was time for them to return to China, punctuating her words by throwing a knife down on the table before her.

Returning to China in 1906, Qiu Jin ramped up her involvement with anti-Qing revolutionary groups, working both to transform society and bring down the dynasty. She launched a journal, Chinese Women’s Journal 中國女報, and traveled around the Yangtze delta gathering information and learning revolutionary tactics, including how to make bombs. In her book Burying Autumn, Hu Ying describes Qiu Jin’s visit to the tomb of Yuè Fēi 岳飞, a 12th-century martyr who died defending China against northern invaders, foreshadowing Qiu’s own fate.

In the summer of 1907, Qiu Jin was the principal of Datong Academy — supposedly a progressive school but in fact a front for a revolutionary cell. When the school’s former director (and Qiu Jin’s cousin) was captured on July 7 after assassinating the Manchu governor of Anhui Province, Qiu Jin’s connection was revealed and several hundred Qing soldiers arrived in Datong to arrest her. Warned about the troops in time to escape, Qiu Jin instead decided to accept her fate.

Interrogated for the last time in the wee hours of July 15, Qiu Jin refused to confess, instead writing down the poem, hinting at autobiography, quoted at the start of this column. Resigned to her fate, she asked that she not be stripped naked for her execution, and that her head not be displayed publicly.

Two days later, at Shaoxing’s execution ground, as described by Hu Ying in Burying Autumn: “[Qiu Jin] wore a white shirt, a plain black jacket and pants, and leather shoes. Her legs were shackled and her hands tied behind her back. Armed soldiers lined the street from the Shanyin government office all the way to the Xuanting Crossroad. At the time of the Execution, she did not say a word.”

Qiu Jin gave her life for a cause. At a time when so many around the world are struggling against injustice and making sacrifices to build a better world, I was moved by Qiu Jin’s last words, but even more so by this poem from 1904, addressed to the husband she had just left, which reflects on the costs of her struggle. Translated below by Hu Ying, Qiu Jin’s words make clear that she was not just a revolutionary firebrand, but a human being, who felt love and loss even while she worked for what she believed was right.

For what is the autumn gloom not lifted?

A hundred sentiments mingle in my heart that cannot be dispelled.

Unable to avoid the typical pitfall,

Our love turned to resentment.

With nothing to call a home,

I owe you much.

Looking back, how sad the day we parted;

Dumb-hearted, [I] still couldn’t let go of our nuptial tenderness.

If there is real sorrow in life,

One must avoid listening to the sad sound of wind and rain.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column. Last week:

Kissinger’s secret trip in 1971 that paved the way for U.S.-China relations