Doomsday scenarios and optimism: Next-generation China scholars on U.S.-China relations

With China’s borders shut to Americans (and vice versa) and the U.S.-China relationship worsening by the day, young students and professionals who want to pursue a career in China are finding that the center has shifted from under them, with their respective countries continually pulled further apart.

At first, the news about a virus sweeping across China didn’t concern Beijing resident Brian Drout. He was confident that authorities would get it under control — until he heard news that Hong Kong was partially closing its land borders as the virus worsened on the mainland. Drout rushed to book a 3 a.m. flight to the city, leaving Beijing and the virus behind.

He expected to return within a few weeks after Beijing controlled its outbreak. Instead, COVID-19 spiraled into a global pandemic, putting his career plans on hold. “People like myself who want to be back in China working are not able to do so,” he said.

After blocking most foreign visa holders from entering the country in March, China has only allowed a select few foreigners to reenter the country. But it’s not the only factor affecting people like Drout: the rapid decoupling between China and the U.S. has led to expulsions of journalists, diplomatic gridlock, and increasing suspicion of foreigners. Other countries are also swept up in the clash between the two largest economies.

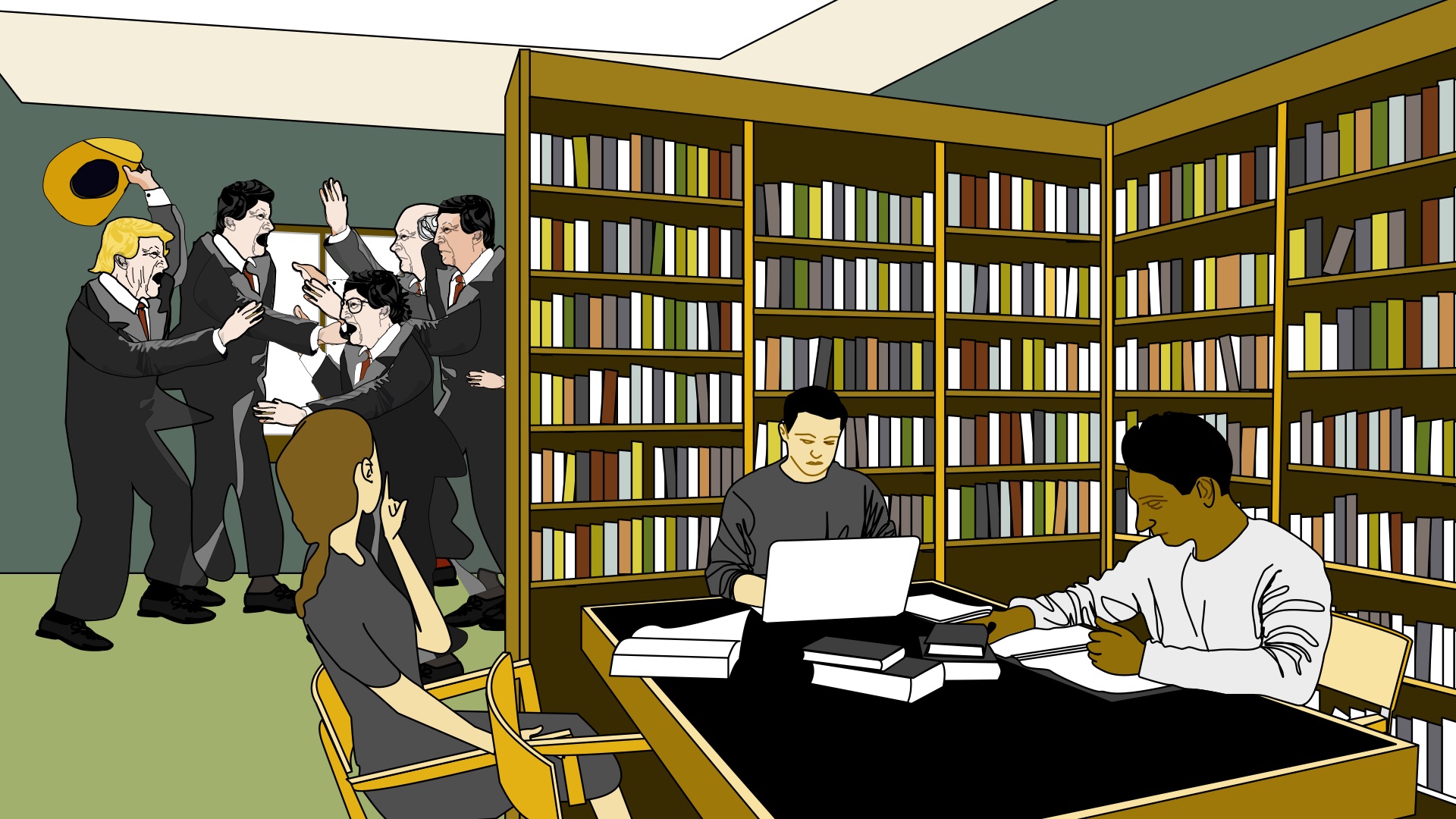

Young scholars and professionals are crucial to China’s foreign relations, leveraging educational experiences to keep communication lines open on a personal level. But they’re learning the hard way that the views they studied in class — that engagement and globalization will invariably lead to positive relations and stronger bonds — don’t always apply in the Xi and Trump era. With China’s borders virtually slammed shut, and the U.S.-China relationship worsening by the day, paths to study and work in China are dissolving.

China has been projecting itself as a leader for a post-COVID-19 world, but the world may not share the enthusiasm. Inside China, opinions are growing more nationalistic, just as outside, attitudes toward China are becoming increasingly negative. Yet despite the hostility and uncertainty that young China scholars and professionals face as they consider their future careers, the alternative of mutual ignorance and distrust feels far worse.

‘Doomsday approaching for U.S.-China relations’

“I was honestly really optimistic about the China-U.S. relationship over the last three years,” said NYU Shanghai Class of 2020 graduate Isabel Adler. “But I think COVID is going to set the clock back like 20 years…And with the current state of the executive branch of the government, I can see doomsday approaching for U.S.-China relations.”

The relationship between the Trump and Xi administrations have been characterized by aggression and conflict, catalyzed in high-profile crises: the ongoing trade war, arrest of Huawei CFO Mèng Wǎnzhōu 孟晚舟, and restrictions for journalists in both countries. Even non-U.S. citizens in China are feeling the strain.

Brazilian Thiago Bessimo graduated from the Yenching Academy in 2018 and has since founded his own think tank covering China in Brazil, Observa China. Despite not being American, he recognizes that the future of China studies is linked to the U.S.-China relationship, and his ability to access the considerable educational resources of both countries. “If I’m studying China, am I supposed to go to China for a degree and not go to a recognized university, or go to the U.S. to a ‘brand name’ university but not have the Chinese experience?” he asked. “What the U.S. does affects other countries when it comes to studying China.”

Young China Watchers’ annual Pulse of China surveys captured the shift in mood from 2018 to 2019. In 2019, 41% of survey respondents felt negative about China’s impact on global affairs, compared to a mere 26% in 2018. Though confidence in China as a global economic power increased, concerns about China as a global military or governance power grew in 2019. And while observers are confident in China’s economic and technological growth, the majority believe China is negatively impacting international institutions and human rights.

Rising China scholars have had to reevaluate their assumptions. “I subscribed to the conventional wisdom that democratic reforms must eventually flow from sustained economic growth, and thought that democratization [would equal] better relations with the U.S.,” said Yale junior Joelle Besch, who has studied China for years. Due to COVID-19, she was forced to cancel her plans to research Chinese mental health interventions.

“What I’ve seen during visits to China and in the news over the past five years has led me to change my position,” she said. “I’m very pessimistic about U.S.-China relations.”

Career paths on pause, or reconsidered

In 2018, 95 million foreign nationals crossed China’s borders, but MERICS reports that “China in the last ten years has become considerably less accommodating,” particularly over border management and resident permits. Additionally, fields like journalism, human rights, research, and even foreign nonprofit work (which is controlled by police authorities) are very risky.

China’s relations with a number of countries, including the U.S., UK, Australia, and Canada, are at their lowest point in years. Foreigners risk being used as pawns: China’s expulsion of journalists and imprisonment of Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor show that even a legitimate visa or job is not enough to guarantee stability and safety.

Besch studies human rights, and believes she won’t get to live or work in China because of this choice. She’s not the only one: China’s rising nationalism and suspicion of foreigners are realities. Xenophobic and racist backlash against a February plan to reform permanent residence policies for foreigners only proved that at least some elements of Chinese society don’t welcome international neighbors.

“It feels like they’re trying to get rid of foreigners, actually,” said Russian Yenching Academy scholar Ekaterina Kologrivaya. “I do understand the very savage nationalistic issues in China and I cannot ignore them, fortunately or unfortunately…at some point, I might not be able to live in this country,” she said.

American Hannah Corn studied in Beijing and Xi’an on a Fulbright scholarship in 2019, but cites censorship and free speech issues as major obstacles to a career on the mainland. “At the end of the day, to make real change and feel like you are making an impact in your work might be difficult in China,” she said. “There’s definitely outlets for expression, but it’s difficult.”

The optimists

Are the risks, discomforts, and international tensions of staying in China worth it? Many young people preparing to study or do business with China think the perks outweigh the perils, and are committed to engaging with China despite the challenges that lie ahead.

“China isn’t going anywhere, and China has made its mark on the global stage,” Corn said. “As a leader, whether you like it or not, China is there…There are lots of ways to engage with China other than just saying ‘China’s economy is large and that’s why we have to pay attention to it.’”

“If people aren’t committing to China long-term for a career path, it’s not sustainable,” said Adler. She plans to work in the music industry connecting the U.S. and China, and credits educational programs like NYU Shanghai with helping change U.S. perceptions of China from a “trapped-in-the-past military state.”

As COVID-19 hastens the breakdown of U.S.-China relations and casts doubt on the future, a new generation of China scholars are promoting the value of education as a way to combat the mutual distrust displayed by politicians at the top.

“Making meaningful connections across cultures to alleviate tensions like we’re seeing right now is important in global relationships,” Drout said. “COVID forces people to reflect on the status of those goals or initiatives.”

Like Drout, Bessimo values his experience studying abroad in China and believes keeping lines of communication open through education is necessary for future relations. “Just the fact that you maintain dialogue and maintain relations and keep the students coming is a sign that China still is interested in a relationship with the U.S.,” he said.

Despite being locked out of the mainland by the pandemic, Drout is relentlessly positive about these goals. “I want to believe there’s value and good ideas on both sides and there are ways to achieve that understanding,” he said. “I’m not naive, but I want to be long-term optimistic.”