‘Shanghai Triad’: Zhang Yimou’s gangster drama told through a child’s eyes

It’s actually unfortunate that the English title is "Shanghai Triad," which gives a dishonest emphasis on the mobsters. The Chinese title, taken from the lyrics of an old lullaby, better represents the movie’s theme of traditionalism or nostalgia clashing with modernity.

One Second (一秒钟 yī miǎo zhōng), the story of an escaped prisoner looking for a special propaganda newsreel during the Cultural Revolution, has been MIA since being suddenly pulled from last year’s Berlin International Film Festival. (Officially, due to a “technical problem,” but more likely because of worries over its controversial historical setting back home.) Another project, the spy thriller Impasse (悬崖之上 xuányá zhī shàng), focuses on a secret team investigating Japanese wartime atrocities in Manchuria during the 1930s. COVID-19 put production on hold for a while, but since filming restarted in the spring, we still only have a poster and synopsis to go by. When either of these works will see the light of day is anyone’s guess, so it really came as a relief last month that Zhang’s other new movie finally dropped a trailer. Under the Light (坚如磐石 jiān rú pánshí), a flashy crime film about a cop on the trail of a shady businessman, is expected to be released later this year.

One Second sounds like the kind of classic historical drama that Zhang is well-known for. Impasse and Under the Light, however, appear more atypical for the director. Zhang hasn’t dabbled much in these genres before, and the closest relations are oddities from his early career. Codename Cougar (代号美洲豹 dàihào měizhōu bào, 1989) was a brainless political thriller that starred Gǒng Lì 巩俐 as a stewardess on a Taiwanese plane hijacked by terrorists. Shanghai Triad (摇啊摇,摇到外婆桥 yáo a yáo, yáo dào wàipó qiáo, 1995), also featuring Gong, was a gorgeous take on old gangster movies that’s worth revisiting before Under the Light.

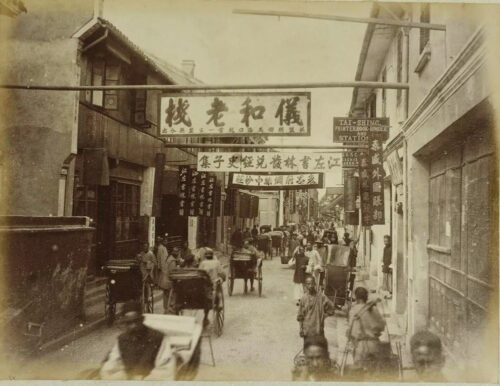

Loosely adapted from a novel by the Shanghai-based author Lǐ Xiǎo 李晓, Shanghai Triad takes place over a period of seven days sometime in the early 1930s. Tang Shuisheng, a wide-eyed country boy, has come to Shanghai with his uncle. Shuisheng is quiet and naive; he’s never seen a phone or ice cream before, and when somebody asks whether he’s ever slept with a woman, he points to his mom. In a glitzy, decadent city, where gangsters and prostitutes are everywhere, Shuisheng is hired to work for a crime boss also named Tang. The boss lives in a massive mansion, where Shuisheng is expected to wait hand and foot on Tang’s mistress, a sharp-tongued singer named Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li).

In contrast to her stage persona, Jinbao is bitter and unhappy, hopelessly imprisoned by Tang. She takes her feelings out on Shuisheng, scolding him for the slightest things, and making sure that the teenager knows that he’s a country bumpkin. As he’s further exposed to Jinbao and Tang’s seedy world, Shuisheng can’t help but long for home. After a bloodbath in Tang’s palace with a rival gang, however, Shuisheng is left wanting revenge before he can leave his employer. Along with Jinbao and the rest of Tang’s retainers, he’s dragged to an island to escape the fall-out from the gang battle. Cut-off from the corruption and violence of the city, the secluded island feels like a trip back into time. Jinbao is impressed by the simplicity of a local woman and her daughter, but nobody can escape from Tang and Shanghai, and by extension, the chaos and materialism of the modern world.

Coming off the heels of his tumultuous historical drama To Live (1994), Zhang Yimou intended Shanghai Triad to be a safer, conventional movie, of the sort that wouldn’t draw the ire of censors. The first half, with its cabarets, shoot-outs, and honorable gangsters certainly seems familiar. It glitters in red and golden colors, opulent, yet on a closer inspection, hollow. But all these tropes are necessary for the second half, where they’re subverted and toyed with, to the point that Shanghai Triad doesn’t have any of the glamor or heroism of the usual gangster flick. It’s actually unfortunate that the English title is Shanghai Triad, which gives a dishonest emphasis on the mobsters. The Chinese title, taken from the lyrics of an old lullaby, better represents the movie’s theme of traditionalism or nostalgia clashing with modernity.

Another remarkable touch is the narrative’s focus on Shuisheng. Instead of depicting the story through one of the criminals, we witness it from the silent, innocent perspective of a boy who’s very much an outsider. He’s practically a voyeur, peeping and stumbling on secrets that we only gradually understand. At several points, we’re even treated to some long, masterful POV shots from Shuisheng’s eyes, as he walks through a corridor, and later, finds himself hanging upside-down from a rope.

True to Zhang Yimou’s expectations, Shanghai Triad was approved by censors. Unlike To Live 活着, which infuriated the Chinese government, it played at the Cannes Film Festival without incident. In a way, it marked the end of an era for Zhang. After a string of seven movies together, Zhang and Gong Li ended their romantic and artistic partnership, choosing not to collaborate again for another decade. As a “safe” movie, Shanghai Triad also saw Zhang’s transition from an independent critic to the mainstream filmmaker who would go on to make epic wuxia blockbusters. Regardless, whether he’s making acclaimed historical dramas or escapist genre fare, movies like Shanghai Triad prove that Zhang will always be a director to keep an eye on.