She weaves baskets from a single palm leaf and builds sofas from five lengths of bamboo. She knows the delicate art of Shu embroidery, how to grow silkworms for her own silk quilt, and has reared ducks from chicks just so she could have duck eggs for one single recipe.

This is the domain of Lǐ Zǐqī 李子柒 (the pseudonym of Lǐ Jiājiā 李佳佳), whose idyllic pastoral vlogs in deepest rural Sichuan have earned her over 50 million subscribers across Chinese streaming platforms.

She’s shy but tough, a jack-of-all trades, combining cutesy charm with no-nonsense hard labor. She can as ably build a dry stone wall as slap, stretch, and twist dough for Lanzhou beef noodles; haul in sacks from the rice harvest as delicately pinch shut the corners of a wormwood dumpling. Her rustic and unpretentious charm has struck a chord overseas, where she has 11 million subscribers on her YouTube account.

Who is Li Ziqi?

Her early life, as she tells it in the few interviews she’s given, is about as Disney princess as the horse she sometimes rides, clad in a Mulan-esque gown and red riding hood.

Born in Sichuan in 1990, her parents divorced when she was young. The death of her father when she was 6 left her at the mercy of a wicked stepmother, whom Li says treated her cruelly, dragging her by the hair, pressing her into the gutter, and giving heavy beatings.

She was taken away by her grandparents to live in their small village community nestled in the bamboo forests of rural Sichuan. She would walk through its glades hunting for beetles, or watch her grandfather chop down trees to make furniture. She was his assistant, helping him in the fields at harvest time, and also her grandmother’s when she was cooking.

Her talents were forged through necessity. “It used to be for survival,” she told People’s Daily. With her grandfather dying when she was in fifth grade, Li and her grandmother had to put food on the table at a time when roughly half of the rural population was living below the national poverty line.

At 14, she dropped out of school and moved to Mianyang City to support the family. For eight years the city brought struggles of its own; she worked long hours as a waitress for 300 yuan ($40) a month, then as a DJ (the editing skills for her videos came from here), sleeping rough under bridges or on park benches.

When her grandmother fell ill in 2012, she returned to care for her. She noticed her older brother posting guitar videos on Meipai, a Chinese video equivalent of Instagram. After much trial and error, in 2016 she settled on home cooking, recording with her phone at the start.

She had been told by a teacher friend that some of her students believed rice grew on trees. Her videos gave an idea of where Chinese food comes from.

Her first attempts were lackluster, filled with dull panning shots, muzak, heavily filtered or overexposed footage, DIY explanations to viewers who would never have the time in their busy city lives to emulate her way of living. But that would change.

Fame and fantasy

With help from technical advisers, she changed her style and began uploading to Weibo instead. She purchased a tripod camera which she operated herself. She now ignores the camera and doesn’t speak, except when chiding puppies or passing jokes with her grandmother, who occasionally pops into shots.

No more words of instruction. Chinese viewers are there to watch, rather than emulate her lifestyle. They don’t want her skills, only to catch a glimpse of a world they’ve lost.

Today, 60% of the population live in cities, with rural areas associated with poverty and the bad old days of pre-boom China. The primary function of the countryside for urbanites is as an escape from the competition, concrete and commutes. Li knows it. “In today’s society, many people feel stressed,” Li told Goldthread. “I want them to relax and experience something nice, to take away some of their anxiety and stress.”

It’s visual comfort food. Lambs, puppies, and chicks get star billing. She rides a horse and dresses in hanfu or traditional loose work clothes.

Hardship is implied in the time-consuming labor for each of her dishes, but the traumas of country living are erased. For a woman who prides herself on doing everything from scratch, animals arrive pre-slaughtered. A flood that destroyed her vegetable patch never made it into her videos’ smooth transition of the seasons. Although she can spend months swatting up on a new skill from online videos, she’ll present herself as a flawless master from the start.

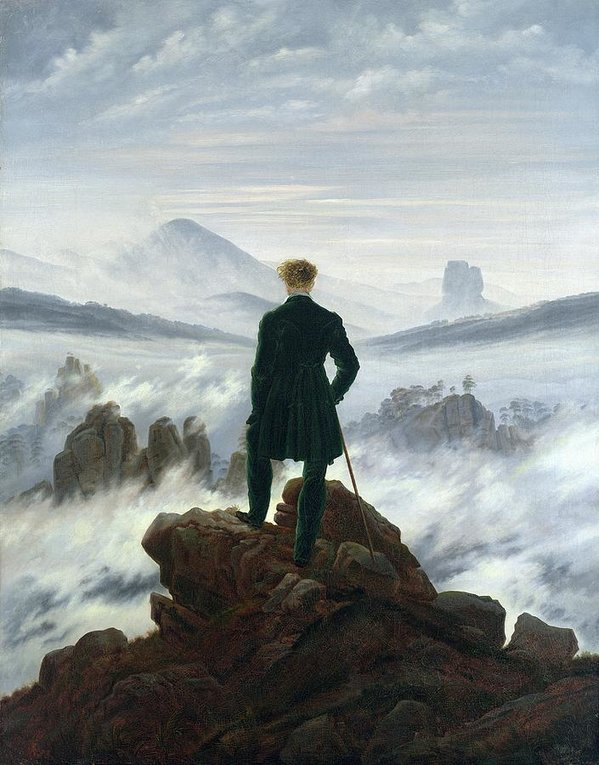

Although Chinese netizens have shown ire at a Vietnamese vlogger seeming to copy Li’s format, in some ways Li herself follows a time-honored artistic recipe: serving up idealized visions of country life. Thus her Insta-worthy modern pastorals echo art history:

Li’s not the only one using the formula. Her doppelgänger can be found in fellow Yunnan vlogger Diānxī Xiǎogē 滇西小哥, who also started recording in 2016, offering similarly aesthetic fly-on-the-wall demos of regional cuisine.

But it’s possible for Li’s videos to look too perfect. She’s been accused of misleading viewers, who believed her videos were too seamless and high quality to be created by a local country girl. She disproved this with a video of outtakes.

Seamless editing implies a smooth life, resonating with many desiring simpler, calmer living. “After retiring, I want to live like this,” says one Douban user. “I have to live in the mountains and rivers. I’ll have a piece of land, a house, a companion, and raise a dog…You don’t have to worry about work and the world is beautiful.”

Country matters

Perhaps some of Li’s magic comes from portraying a dying world as youthful, even immortal — even if it’s not the reality. Back in March 2014, the government pledged to move 250m to the cities by 2026, in their quest to eradicate rural poverty. Since then, high-rise suburbs have plowed through mountains, fields, and valleys. Children grow up with little knowledge of the countryside or the skills that came with life there. Farmers who had lived on the land their entire lives are forcibly removed to cramped high-rise apartments, with no sights out the window but dozens of other similar monoliths.

The state upholds Li even as they destroy the world that nurtured her. In September 2019, the People’s Daily gave her their “People’s Choice Award,” with other state media hailing the positive national image she sends abroad. Without saying a single word, she “promotes Chinese culture in a good way” says CCTV. State media is also promoting other traditional craftspeople doing well on YouTube, realizing the capital to be found in professionally-shot videos of Chinese culture.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series.