53 days in Wuhan: A frontline doctor on what he learned

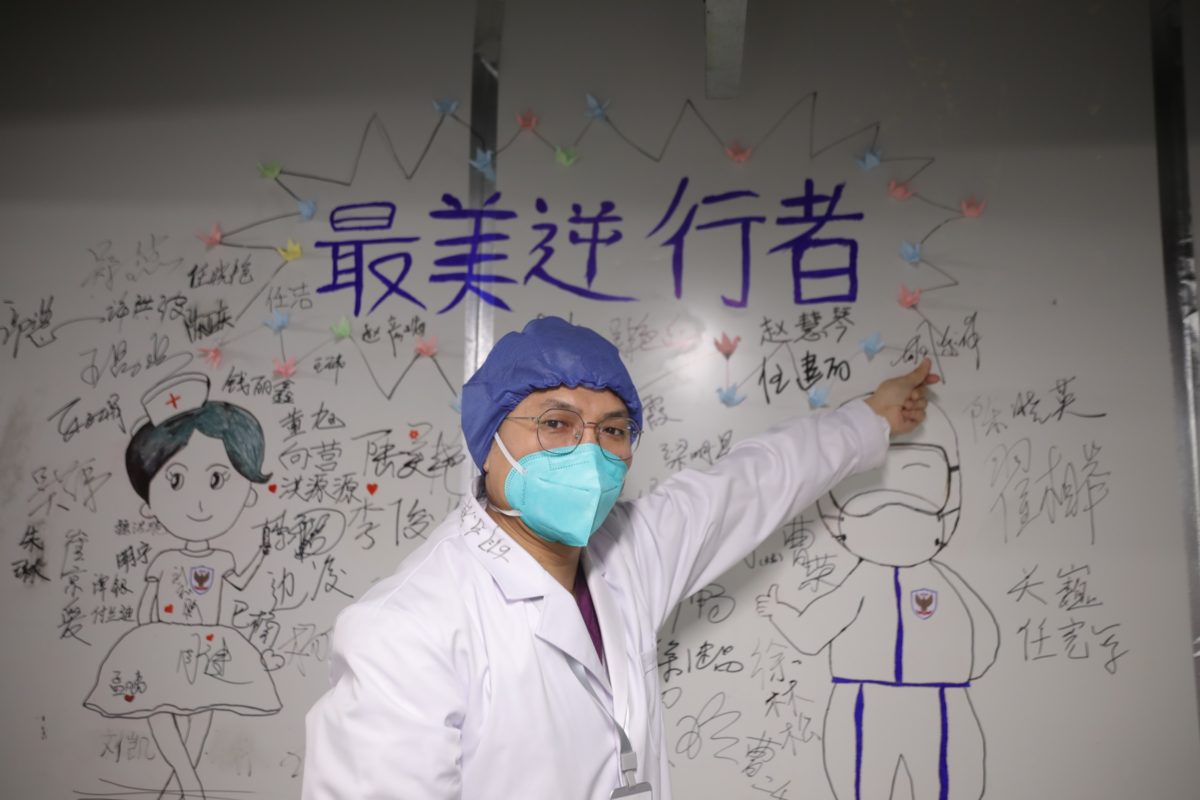

In February, thousands of doctors and medical personnel were sent to Wuhan, the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak, to help the city combat the virus. Their stories are ones of perseverance, courage, and lots of hard work.

On Thursday, the northeastern port city of Dalian in Liaoning province had its first reported cases of COVID-19 in 111 days. Four days later, eight other cities had reported cases, leading officials to initiate mass-testing in order to nip this outbreak in the bud. They know how quickly the virus can spread if they don’t.

Hú Dōngxiáng 胡东祥, a doctor based in Chaoyang City, about a three-hour train ride away from Dalian, knows it, too. Earlier this year, he spent 53 days in Wuhan as part of a medical team sent there to help combat the coronavirus.

Recalling his experience in Wuhan as “very unforgettable,” Hu said: “If we’re needed for a second time to fight against the virus, I’ll still jump into it without hesitation.”

Hu was stationed at Leishenshan, the second makeshift hospital in Wuhan for treating coronavirus patients, where he experienced stress, fear, and a distinct sense of responsibility.

“I still think of those days back in Wuhan often,” he said. “Every day remains a vivid picture in my head.”

I recently interviewed Hu to ask about his experiences as a frontline doctor. What follows are his answers, edited for length and clarity.

It was confirmed that we would be sent to Wuhan on February 8, the eve of the Lantern Festival, a day that’s supposed to be filled with celebrations and family gatherings. Along with 34 other doctors from [Liaoning] province, we set off early in the morning the next day, not knowing what exactly to expect.

On the way to the hotel, I barely saw any cars on the street. At that time, Wuhan was like a deserted city. Only a few traffic police or delivery people could be seen from time to time.

Right upon arrival, we headed to Leishenshan, which was still in its late-stage construction. We received related training for a few days before taking over the A1 Unit of Infection Department I on February 13. We spent another two days helping equip the wards, and started taking in patients on the 16th.

Our unit had 40 beds, and all the beds were taken the first day. Confronting 40 anxious faces was when we started feeling the real pressure. None of us had any experience in treating COVID-19 or anything similar. It felt like fighting an enemy we never met and knew little of.

We were so overwhelmed, especially in the first few days. It was usually already two or three in the morning by the time I’d get back to the hotel. We were also short of PPE in the beginning, but fortunately the problem was soon resolved thanks to donations from all over the nation.

Every day in my daily rounds to the wards, what I heard most from the patients were their genuine thanks. Their “thank you” made me emotional sometimes, at the thought that behind each of the patients, there’s a heartbreaking story — most of them had lost one or even more family members during this time.

I had a patient who just lost her husband from the virus; another patient who lost her younger brother and mother; a single mom who had to leave her young child behind to be taken care of by the neighborhood office…

I also remember this old lady who lost her husband in the pandemic. The blow was so huge for her that she refused to accept any medication. We had to transfer her to another hospital. I didn’t know what happened to her later. I hope she recovered and is having a good after-pandemic life.

Every day in my daily rounds to the wards, what I heard most from the patients were their genuine thanks.

For general treatment, we were following the clinical guidelines released by the National Health Commission. Crossing the river by feeling the stone, the guide was updated continuously and regularly. In mid-March, it was updated to its 7th version.

We treated patients according to the guide, combined with our clinical experience and the patient’s condition. As time went on, we got to know better what kind of treatment works more effectively for certain patients, and things became slightly less intense.

I spent long hours in the hospital, to the point that for each patient’s CT scan, I could tell which one belonged to which patient without checking the name.

We sometimes spent hours providing emergency treatment to patients whose condition suddenly worsened. By the time the patient came out of danger, we would be so exhausted both physically and mentally.

There were days when the number of new cases reached the thousands. I’m kidding you and myself if I say that I wasn’t afraid during the process. When we learned about the death of another medical staff, we couldn’t help but worry about what will happen to us. But facing the patients, we had to leave that fear behind. All we could think about was the patients. Would we get infected? We had no time to think about that. Even if I did, I’d like to believe that the hospital would try its best to save my life.

I suffered from insomnia in Wuhan. Although I felt extreme exhaustion after working long hours, I couldn’t sleep well. No matter how little sleep I got, I needed to get up at six in the morning to fight for another day.

I’m not alone: many medical staff here suffered from sleeping problems. I think it’s from the pressure. Our hospital even founded a team specifically for consulting medical staff and providing psychological support.

We received 62 patients in total, including those from Fangcang hospitals after they closed on March 11. (Patients stayed for an average of 18 days.) Besides two cases that became serious, with the patients transferred to the ICU, the other 60 patients were discharged in the end. This is what made me most proud and happy.

When our unit declared zero cases in late March, we were overwhelmed by so many mixed emotions that I simply don’t know how to put it into words. We soon got the announcement that we could go home.

We left Wuhan on April 1. I finally had a good sleep back home. I started seeing life from different perspectives. My priorities become shuffled too. Things that used to appear ordinary to me now seem precious.

But after nearly two months of life in a pressure cooker, it’s taken me some time to adjust to “normal” life. I often recall those days in Wuhan and the people I met there. For each photo we took in Wuhan, I have a story to tell.

During my stay in Wuhan, I’ve been keeping a diary. No matter how late it was when I got back from the hospital, I insisted on finishing a diary entry before going to bed. I think it was a way to release some pressure after long hours of work. I want to keep my experienced record to show what life was like during such a special time.

I’ve also been so touched and impressed by what every ordinary Wuhan person did and the courage they showed. Their names are unknown to the public, but they’ve contributed so much, including all the hotel staff providing the warmest service for us, the traffic policemen who escorted us to the hospital every day, and the canteen worker who spent at least four to five hours cooking for us in the hospital. My gratitude toward them is beyond words.

If I ever visit Wuhan, I hope I can simply visit as a tourist, and that I don’t need to worry about anything but to appreciate the beauty of Wuhan.

April 8 is the day Wuhan lifted the lockdown. All the lights along the road outbound from Wuhan were lit up until midnight. With other medical staff, we sat together to see the ceremony of the lighting. Many burst into tears. For us, I think we will forever have a tender spot for Wuhan.