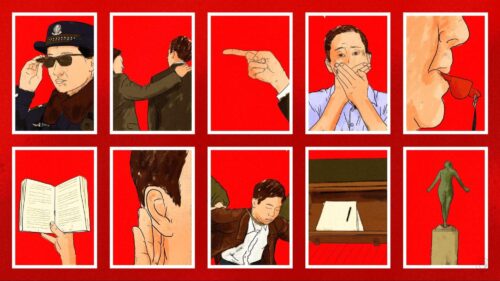

After TikTok, what happens to internet freedom?

The meaning of internet freedom is changing. Under Trump, the U.S. seems set to tell China it was right to distrust foreign-owned social media apps.

For much of the 21st century, Americans were internet-optimists, believers that a free and accessible internet would strengthen democratic movements across the globe by providing individuals with a tool to access information and communicate outside the reach of repressive governments.

Those ideas were always poorly defined, but for the better part of two decades they found their way into American foreign policy in the form of two steady principles: a laissez-faire approach to commerce on the internet and an anti-censorship, human rights-centric approach to its use.

Last weekend, President Trump threw the largest wrench into that first principle in more than two decades. After a month of rumor and speculation, Trump announced his intention to ban TikTok, the wildly popular short-form video application, over concerns that Beijing could force the app to collect sensitive data on Americans or manipulate the content that appears to users.

He subsequently walked that threat back, and now appears content to force its sale to Microsoft.

TikTok may well be a victim of happenstance and pique. The app achieved far more success with U.S. users than any previous Chinese app, but its timing was inopportune, taking off amid a broad unraveling of the U.S.-China relationship. There are rumors that Trump wanted to ban the app because of reports that it was used to undermine his rally in Tulsa.

Still, after years of preaching about the virtues of the open internet to the Chinese, and being rebuffed, the ban represents a jarring reversal for the United States. In effect, it concedes that foreign-owned consumer technology companies can be a tool of subversion, illustrating how a nation that was once a leading evangelist for internet freedom has come to accept that the internet can also be a powerful tool for ill.

“This is being driven by a disillusionment with the ideas that undergird the open internet, which was that the internet was going to challenge autocracies and democracies would be fine,” said Adam Segal, director of the Digital and Cyberspace Policy Program at the Council on Foreign Relations, when the ban was still only rumored. “What we’ve seen is kind of the opposite.”

As the largest Communist country after the collapse of the Soviet Union, China was once seen by many in the West as a test case for how the internet could pry open authoritarian information regimes. When asked in 2000 what he would do if China tried to “crack down on the internet,” then-president Bill Clinton famously quipped that regulating the internet was like “nailing Jell-O to a wall.”

Government officials like those in China tended to look skeptically on American support for an open internet, seeing it as a cover for regime change, the prying open of foreign markets for American technology companies, or both.

But even as China turned its internet into a tool for censorship and surveillance, Americans held firm to the belief that China would eventually have to choose between restricting growth to retain control over its citizens or permitting internet openness to access economic innovation.

The internet was a win-win proposition for the United States. And then came 2016.

“If we are going to start blocking Chinese things just because they are blocking our things, then we’re just saying, ‘In order to spite China, let’s turn ourselves into China.’” —Rebecca MacKinnon, Director, Ranking Digital Rights, New America Foundation

The 2016 Russian election interference campaign turned misinformation and disinformation into household terms for millions of Americas.

Alec Ross, who served as Director of Innovation for Hillary Clinton’s State Department from 2009 to 2013, played a central role in the department’s work on internet freedom during the Arab Spring. Ross believes that the problems associated with internet policy have changed fundamentally in the seven years since he was in government.

“One of the big differences between 2020 versus 2016 is, the very idea of what is a fact and what is true is far more litigated today than it was even five years ago,” Ross said. “Misinformation was a non-issue when I was in government. I mean, it was a complete non-issue.”

Ross blames cynical politicians and external actors like the Russian government for the decay of the information environment in the United States. Either way, he has a point. According to a 2018 poll by the Pew Research Institute, 73 percent of the American public believe that Republican and Democratic voters disagree not just on policy but “basic facts.”

Central to those concerns are large technology and social media companies. And while the threat of misinformation and disinformation on a foreign-controlled application like TikTok may be greater than on a U.S.-owned application like Facebook, it does not go away.

The platforms that were abused during the 2016 election were American-owned.

“Those institutions are the fulcrum of how people get information today. They are much more powerful than anything the Russian Internet Research Agency did to the United States in 2016,” said Eric Novotny, who has served as both senior adviser for the State Department’s Digital Media and Cybersecurity division and senior adviser at USAID’s Democracy and Technology.

“On social media, you don’t even think you’re being exploited because you’re having fun,” continued Novotny, who eschews all social media except LinkedIn. “The whole model has to change and it’s very difficult to do that, because people now expect that they get these services for free.”

The United States has taken action against foreign technology or social media companies before. Russian anti-virus maker Kaspersky, Chinese telecommunications giants Huawei and ZTE, and Grindr, a U.S.-based gay dating app later purchased by a Chinese ownership group, were all subjected to government-mandated restrictions.

But those actions moved through established bureaucratic processes, like the Treasury Department’s Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, or applied only to federal networks or contracts.

And whereas those actions centered around straightforward concerns of espionage or critical infrastructure protection, TikTok has an innocuous-seeming user base of teens, tweens, pre-teens, and post-tweens. It would also be the first large-scale consumer product to be blocked in the United States.

“There are several cases that are tangentially related or might have somewhat applicable precedents, but I would generally say that, no, there is no analogue for what is being discussed, which is a broad ban on an application,” said Justin Sherman, a fellow at the Atlantic Council, when the ban was still only rumored. “There’s not anything else that’s direct to consumer in the same way, where there are these censorship and information manipulation concerns.”

When it comes to internet freedom, the concerns around censorship and information control are new, and exceptionally difficult to manage. Absent changes to U.S. data privacy law, it is unclear whether forcing the sale of TikTok to a U.S. company would solve the core problems associated with the app.

“We have a big set of security problems in terms of both lack of corporate responsibility across the board and lack of government doing its job across the board, and I think the rose-colored glasses that the public has been wearing about these companies has permitted them to be irresponsible,” said Rebecca MacKinnon, the author of a 2012 book on internet freedom who currently runs a research program at the New America Foundation.

“The danger is of course that people just enact measures for political expedience that don’t actually protect anybody, and TikTok would be one of those,” MacKinnon cautioned. “If we are going to start blocking Chinese things just because they are blocking our things, then we’re just saying, ‘In order to spite China, let’s turn ourselves into China.’”

Social media platforms, TikTok included, can be used both for good and for ill. There are no easy answers when it comes to the balance between under-regulation and over-regulation.

Either way, it is clear that the meaning of internet freedom is changing.

Michael Posner, a former Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor during the Obama Administration, believes that the U.S. government and social media companies need to take a more proactive approach to combating disinformation and misinformation.

During his time at the State Department, he helped draft three of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s landmark speeches on internet freedom. In each speech, he said, he included a famous refrain from U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis: “The remedy to bad speech is more good speech.” (He paraphrased.)

“In 2010 or 2011, I firmly believed that was the answer,” he said. “I don’t believe that anymore.”

Also see: