This Week in China’s History: August 22, 1870

The summer of 1870 was a tense time to be a Qing official. The Taiping War had ended, but the weakened central government was scrambling to recover its equilibrium amid regional rebellions and international encroachment. Now, war with France seemed imminent, following the massacre killing of several French priests — and dozens of Chinese Christians — in Tianjin. Regional governors were anxiously coordinating their policies with one another and with the imperial court in Beijing. Discussions over how to respond to ongoing threats from both within and without dominated both the court in Beijing and regional offices.

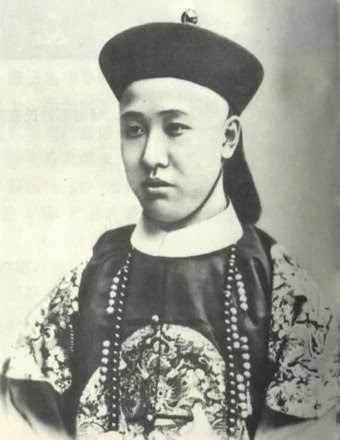

Mǎ Xīnyí 马新贻 figured centrally in these debates. A governor-general and one the most powerful officials in the realm, Ma sat at the same level of government as legendary figures like Lǐ Hóngzhāng 李鸿章 and Zéng Guófān 曾国藩. Ma also coordinated the exchange of technology and methods from Western advisers to the Qing army. On the morning of August 22, Ma conducted inspections of the military preparations in Nanjing and then headed back for his office.

He never arrived. An assassin’s blade found its target as Ma walked through Nanjing’s steamy streets. The next day, he was dead.

The assailant, a man named Zhāng Wénxiáng 张玟祥, was apprehended and, eventually, convicted and executed. This implies that the murder was quickly solved, but the fabric of the killing has threads that extend into many parts of late-Qing society, both profound and mundane, and the case has entered lore as one of the “four mysteries of the late Qing” (清末四大奇案 qīngmò sì dà qí àn).

Born in 1821 to a Muslim family in Shandong, Ma Xinyi started his career by passing the jinshi civil service exam in 1847, a remarkable achievement given the absurdly low pass rates of this time. He scored high enough to qualify for the prestigious Hanlin Academy, a government think tank made up of the top candidates. After a few years in Beijing, Ma was appointed to a bureaucratic post and quickly advanced through the ranks until 1858, when the Taipings captured the city of Hefei, in which he was serving. Blamed for the loss, Ma was punished in Kafkaesque fashion: stripped of his rank and title, but left with the same responsibilities.

Ma then went off script, forming his own private army to fight against the rebels, mainly in Anhui, His success against the Taiping led not only to his reinstatement, but promotion, becoming governor of the prosperous province of Zhejiang just as the war ended. There, he worked with other officials to handle relations with Europeans in the province, and took special interest in applying military and technological innovations to the local military. Another promotion, to governor-general of Zhejiang and Fujian, put him in charge of pirate suppression, and his effectiveness against coastal raiders advanced him yet again, succeeding Zeng Guofan himself as viceroy of Liangjiang, encompassing the provinces of Jiangsu, Jiangxi, and Anhui. In recent decades, this position had been given broad powers and responsibilities over regional taxation, trade regulation, coastal defense, and pirate suppression. Based in Nanjing, this had been Ma’s job at the time of his murder.

A lengthy investigation found that Zhang Wenxiang had acted alone, killing Ma Xinyi as revenge for the official’s effectiveness. Zhang, who had once fought with the Taiping rebel, had after the rebellion worked for several Zhejiang pirates, who resented Ma Xinyi’s actions against their businesses. Zhang himself had a pawnshop in Ningbo — a conduit for pirated loot — that Ma had shut down in his campaign against both piracy and usury. Encouragement from his brigand sponsors and anger over his loss of revenue was enough to spark Zhang to violence. He was executed by slow-slicing — the most anguishing of Qing punishments, in which an executioner works to extend the victim’s life as long as possible while he is incrementally dismembered — seven months after the crime.

But from the start, rumors swirled about the real reasons behind the killing.

The most popular theory centers around the relationship between Ma and Zhang, and Ma Xinyi’s actions during the time of the Taiping War. In this version, when Ma was reestablishing his reputation in that gray area between official army and militia, he fought against a group of bandits. Two of the bandit leaders, unable to defeat Ma Xinyi, joined forces with him. The three pledged an oath — becoming “blood brothers” — and went on to become a potent fighting force. Ma is then alleged to have violated the oath, both by taking up arms against his brothers (when Ma took a higher rank in the Qing army) and for an affair with the wife of one of the brothers. The final proof of his betrayal, Ma killed his comrades. Zhang Wenxiang — part of the bandit group, but not a member of the pledged trio — took his revenge by killing Ma Xinyi.

A second version is that Ma was killed by members of Zeng Guofan’s Xiang (Hunan) Army, who wanted to maintain their power against attempts by the Qing to reestablish their authority. The murder was part of an intragovernment power struggle over the Hunan army.

A third theory was alleged anti-foreignism, blaming Ma Xinyi’s favorable treatment of foreigners (sometimes supported with the rumor that he converted to Catholicism) for his murder. Ma’s connections with Europeans, at a time of numerous anti-missionary killings, is noteworthy, as was his position as liaison with foreign representatives in the Jiangnan region during the rise of treaty ports like Shanghai.

Religious motives of a very different sort are the foundation of yet another theory. As a Muslim, Ma was alleged to be partial to the Muslim rebellions that had broken out in the northwest and southwestern parts of the empire. In this version, Zhang overheard Ma Xinyi’s intention to support the rebellion and, outraged by the treachery from someone who had fought to defend the dynasty against rebellion, killed him to foil the plot.

None of these theories, or any of the several others, has been proven. Officially, Ma Xinyi was a virtuous official killed for his dedication to his duty. Memorial tablets were erected to the fallen hero at places important to his life. In his hometown of Heze, an elaborate memorial hall and tomb, still standing, guard his memory.

But it is the blood-brother conspiracy that has captured the public memory of Ma Xinyi. It was rumored to have been the subject of a question in the local civil service exam. A stage play soon dramatized the theories about the murder, staged in Shanghai just years after the incident, and though its plot has been lost, Cài Dōngfān’s 蔡东藩 1916 collection The Romance of the Qing Dynasty (清史演义 qīngshǐ yǎnyì) told the story as well, and ever since it has remained a staple of fiction, television. There have been four film adaptations, first in 1949, but most famously in a 1973 Shaw Brothers film, Blood Brothers in Hong Kong (retitled Dynasty of Blood for the American release), and most recently The Warlords starring Jet Li and Andy Lau.

So, there you have it: Ma Xinyi. Faithful servant to the Qing who fought to preserve the dynasty and died for enforcing its laws.

Or a treacherous rogue who betrayed his friends’ most intimate trust.

Or an outward looking reformer who was killed by reactionaries who hated his embrace of Western methods.

Or a religious rebel who wanted to split the Qing empire and embrace Xinjiang independence.

One of the “Four mysteries of the late Qing,” indeed.

SOURCES: There is surprisingly little in English about Ma Xinyi. Basic details can be found in Hummel’s indispensable Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period (entry by Fang Chao-yin). There is much more in Chinese, including but not limited to Gāo Shàngjǔ 高尚举, 刺马案探隐 (cì mǎ àn tàn yǐn) (Beijing Library Press, 2001).

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.