“Like endless boiling water, the flood is pouring forth destruction. Boundless and overwhelming, it overtops hills and mountains. Rising and ever rising, it threatens the very heavens. How the people must be groaning and suffering!”

Thus spake the mythical Emperor Yao (尧 yáo), throwing up his hands in despair at the cruelties of nature. It was sometime toward the close of the third millennium BC, and for two generations chaos had become the norm. All rivers between the Yellow River and the Yangtze had risen from their banks, ravaging the land in an unprecedented event enshrined as “The Great Flood” in Chinese legend.

But out of chaos came order when Yao’s successor appointed a man named Yu to solve the problem. Like the Xia Dynasty he founded, Yu the Great ( 大禹 dà yǔ) — he who “Controls the Waters” — is a figure shackled to unprovable myth. But with his system of dredging, dikes, and divisions, his story looms down the millennia. It implies that Chinese civilization and the state overseeing it were born with, and are dependent on, harnessing the power of water.

Who was Yu the Great?

You’ll never get a definite answer. Although his name is first mentioned during the Zhou Dynasty, this was hundreds of years after his own lifetime, c.2123 – 2025 B.C.

All sources were written at least 2,000 years later, during the Han Dynasty. Dozens of cities in China lay claim to being his birthplace. The earliest image of him dates to around 100 A.D., and is appropriately sketchy:

The only identifying element is his “musi,” a traditional hoe and ancient tool for flood control. Modern depictions are more epic, cladding him in the muscles of Hercules or the flowing beard of Moses. Here he is beating back a river demon, the Great Flood personified as a many-headed Hydra of chaos:

Han historian Sīmǎ Qiān 司马迁 believed Yu’s great-great grandfather was Huangdi, the illustrious Yellow Emperor. According to some stories, he was born from the belly of his own father, Gun, who had been dead already for three years. Gun had been charged with controlling the floods but failed miserably.

The Emperor Shun, a man of great virtue, commanded Yu — now his Minister of Works — to continue his father’s projects. He was also to improve infrastructure, agriculture, and transport, Sima Qian wrote he was ordered “to make a division of the land, and following the line of the hills hew down the trees, and determine the characteristics of the high hills and great rivers.”

This was his life for the next 13 years. “With ragged clothes and poor diet he paid his devotions to the spirits until his wretched hovel fell in the ditch…on the one hand he used the marking-line, and on the other the compass and square,” writes Sima Qian. “He made the roads communicable, banked up the marshes, surveyed the hills, told…that paddies should be planted in low damp places.”

Yu was determined to learn from his father’s mistakes with the floods, working out in detail where he had failed. “In order to drain the nine streams into the four seas, I deepened the channels and canals, and connected them with the rivers,” Yu said, according to Sima Qian.

Through a system of canals, Yu divided the rivers, lessening their uncontrollable force, and in the process providing irrigation. It allowed the permanent settlement of China’s fertile river banks.

Such an undertaking was so mighty that legend gives him divine help. He traveled around the country on a 10,000-year-old turtle. River gods provided him with maps of rivers, while channels in mountains were cleaved by his mighty axe.

His superhuman efforts were combined with duty and humility. For 13 years he toiled across the land, never returning to his home and wife. He briefly passed his front door three times over that decade but never went in, not even when his young son saw him for the first time and called out his father’s name. He was no aloof overseer, helping his men dig mud out of his dikes, day after day, year on year.

Yu’s efforts meant the Yellow River didn’t flood again for over a millenia. Emperor Shun was so impressed with Yu’s dedication and virtue that he made the popular move of naming him his successor (Shun’s son was probably less than ecstatic).

Yu’s taming of the floods led to better infrastructure. More reliable roads meant greater state oversight, which could draw taxation and natural resources more easily. Instead of traditional tribal alliances, a more unified state emerged, the emperor conferring titles on vassals and building a social hierarchy. As emperor, Yu also divided his land into nine “zhou” (or “regions”), creating a more concrete image of the territory under his power. It’s from Yu’s reign, his division of order from chaos, that China’s dynastic cycles traditionally start — not stopping until 1912.

His reputation is of being a wise and virtuous ruler, perhaps conjured up by Confucians as a role model for Han emperors. He executed a clan chieftain who was late to a meeting, a draconian example of his obsession with proper governance. Even the ever-critical Confucius said, “With Yu I can find no fault,” praising him for regularly sacrificing to the ancestors, wearing coarse clothes, and eating simple food.

He left this world as vaguely as he entered it. After 10 years of rule he came down with illness during a tour of his eastern lands, just south of modern-day Shaoxing. Today the city boasts an ancient and important shrine to Yu, visited by emperors all down the dynasties to pay their respects.

Après moi, le déluge

Historically, China’s rivers were the responsibility of the state and rigidly controlled. Archaeological evidence points to canal systems being dug to deflect the Yangtze as far back as 5,000 years ago.

They are an indispensable tool which will overwhelm you if set free. Over the past 3,000 years to 1949, the Yellow River re-adjusted its course, with catastrophic consequences, 1,500 times (once every two years, on average). Not for nothing has this river been nicknamed “China’s Sorrow” — the second-largest natural disaster in history occurred when it flooded in 1887, killing anywhere between 900,000 to 2 million people. Its raw power has even been used in war, both by the Ming against rebels in 1642 and the Kuomintang against the Japanese in 1938.

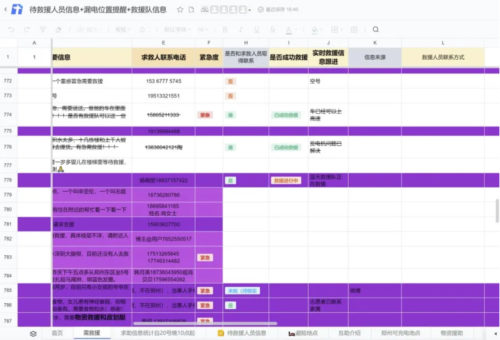

China is now experiencing flooding that is being hailed as once-in-a-century — cities are swamped, national heritage sites are ruined, houses are pushed aside like toy bricks, powerless against the onslaught. The Three Gorges Dam is churning water from all its spillways, desperately trying to lower a water level which has been 10 meters above the official warning level for a month. (It rose to the highest mark in its history last week.) The dam is the only thing standing between 39.3 billion cubic meters of water and 500 million people downstream. If it were breached or collapsed — which some entertain as a possibility — the demons of a modern Great Flood will run rampant on the Yangtze.

In the face of such danger, Yu’s example is a valuable government asset, a tale of hardy Chinese resistance in the face of hardship. On August 18, Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 inspected flood defenses in Anhui. Speaking to a small crowd of onlookers, he praised China’s long fight against natural disasters, including “Yu’s treatment of water.”

“We will continue to [fight],” Xi said. “This fight is not against the heavens, it’s people needing to be more harmonious with nature, following the laws of nature in order to be one with nature.”

But in contrast to Yu’s dredging and dividing, a dam like Three Gorges blocks nature rather than harmonizes with it. It’s a more dangerous method to control floods, the potential for catastrophe woven in if enough resistance builds up behind it. Governments in China have been trying to curb the country’s water for millennia, and now, with technology, they think they are above nature. They try to suppress it.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series.