In TikTok, a bad omen for Chinese technology in Europe

A recent European court decision — aimed originally at data privacy breaches by the United States — may have far-reaching implications for Chinese tech companies. Scrutiny will fall on data-rich companies like TikTok, which was just beginning to soar in Europe, as China has even fewer rule-of-law safeguards than the U.S.

As much of the world has focused on the fire-and-brimstone style tech-protectionism of India and the United States, which both announced surprise decisions to block Chinese mobile applications this summer, a third geopolitical heavyweight has quietly begun to chip away at the growth trajectories of Beijing’s technology giants.

Slowly but surely, headwinds are sweeping across Europe.

This summer, data protection authorities in Holland, Denmark, and the United Kingdom launched investigations into TikTok, while in June the European Data Protection Board established a task force to coordinate action against the company across the union’s 27 member states.

The biggest announcement came three weeks ago, when the French Data Protection Authority, CNIL, disclosed it had launched a fourth probe into TikTok.

Whereas the Dutch, Danish, and British investigations focus narrowly on whether TikTok offers appropriate protections for the privacy of young users, the CNIL probe will examine a broader set of issues, including the company’s transfer of personal data outside Europe.

That aspect of the CNIL investigation will trigger alarm bells in Beijing, and not just because of TikTok.

It follows shortly after Europe’s high court issued a surprise decision affirming rigorous new standards for the transfer of personal data outside the EU, in a ruling designed to ensure that the data protection rights of EU citizens are preserved when personal data moves outside the bloc, where it theoretically sits vulnerable to foreign surveillance.

Those standards will create significant obstacles for most companies that operate within the EU, since cross-border data transfers are common. But it could prove especially galling for Chinese technology companies like TikTok that have sought safe haven in Europe after being spurned by geopolitical conflict elsewhere

Companies that do not stop illicit data transfers risk violating Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Fines range up to 20 million euros ($24 million) or 4% of annual global revenues, whichever is higher.

Collateral damage

Ironically, the ruling by the European Court of Justice was aimed not at China but the United States.

The case grew out of a complaint filed by Austrian privacy activist Maximilian Schrems, who has waged a series of legal battles in the wake of the Edward Snowden disclosures to curb the surveillance practices of the American intelligence community and limit how U.S. social media companies collect data on foreign citizens.

Schrems won a related case that he brought before the European Court of Justice in 2015. For that reason, the second ruling, which is more expansive, has assumed the moniker “Schrems II.”

In the short term, Schrems II will have larger repercussions for the United States. The court simultaneously invalidated a specific EU-U.S. data transfer agreement, known as Privacy Shield, which allowed 5,300 U.S. companies to store the personal data of EU citizens in the United States.

But Schrems II presents a significant regulatory risk to Chinese companies in the long term.

The ruling requires Europe’s regional Data Protection Authorities (DPA) to look broadly at the legal environment and surveillance practices surrounding companies that collect and store the personal data of EU citizens.

Europe has a stricter vision than most when it comes to protecting personal data, so by default, most countries would fail to meet the new standards required by regulators.

Still, scrutiny will fall heavily on data-rich Chinese companies like TikTok because China has fewer rule-of-law safeguards than the United States does — and in the same judgment, the court deemed U.S. surveillance safeguards inadequate.

Politics will also play a part. In effect, the ruling will force Europeans DPAs to weigh their trust that Chinese companies can develop effective corporate workarounds to government surveillance just as the CCP’s reputation in Europe is souring over issues like Hong Kong and COVID-19.

“In 2015, the political focus in Europe was totally on U.S. surveillance,” said Kenneth Propp, who teaches European Union law at the Georgetown University Law Center and is a fellow at both the Atlantic Council and the Progressive Policy Institute. “Over the last five years, there has been an evolution in Europe’s thinking. They are now seeing themselves pressed by China and Russia, and I think Brussels now realizes that the surveillance threat is not just from the United States — and indeed, not primarily from the United States.”

In 2018, Freedom House ranked China the worst abuser of internet freedom based on a ranking that included violations of user rights, in addition to censorship and obstacles to access.

Europe’s third way

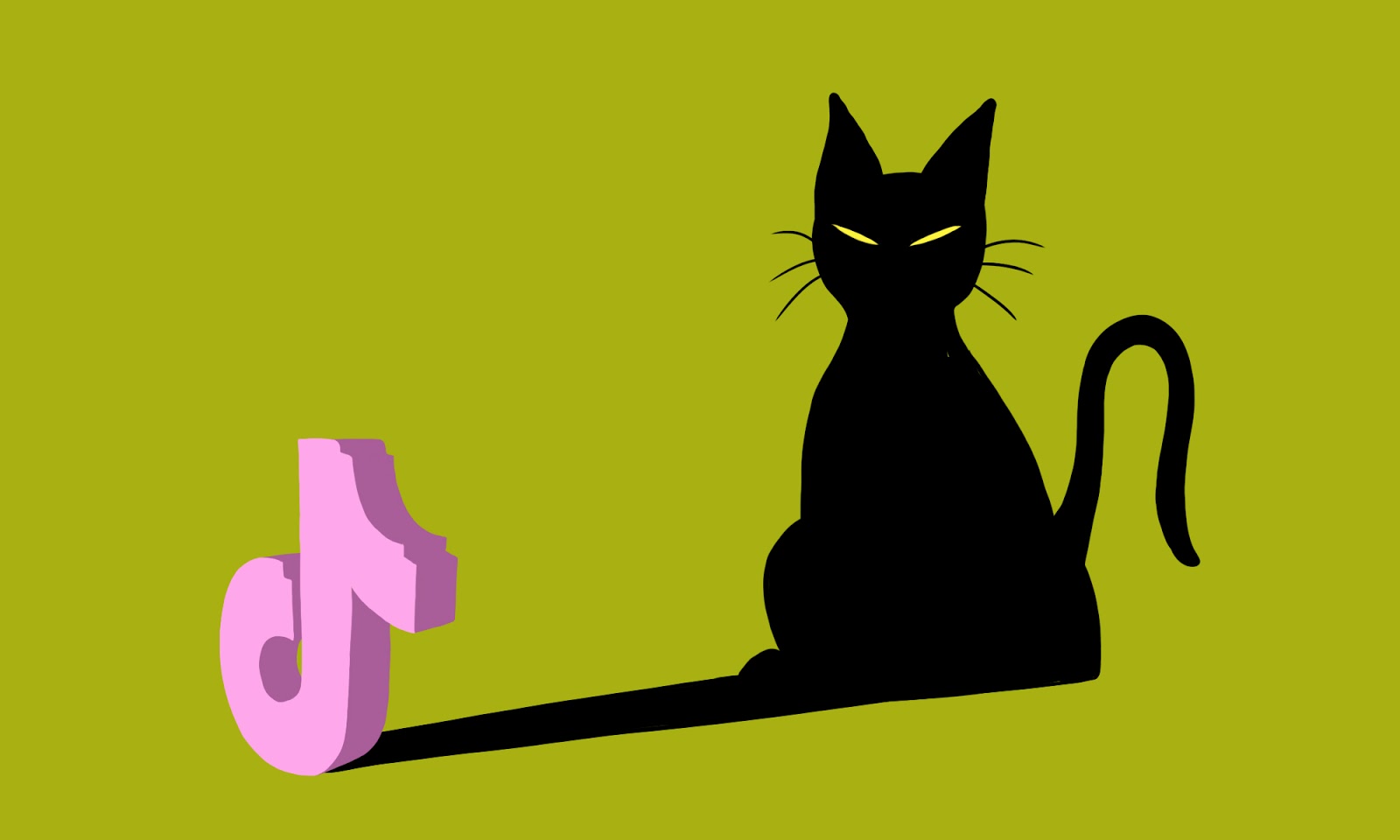

For Beijing, the danger of Schrems II lies not just in the letter of the ruling but the spirit that animates it: European techno-skepticism.

That attitude is cresting at an inopportune moment for Beijing. China’s technology giants, which have struggled for years to extend outside the mainland, were finally making strides in Europe — and none more so than TikTok.

In the second quarter of 2020, TikTok was the second most downloaded app in Europe, according to Sensor Tower, a firm that tracks mobile app analytics. No other Chinese mobile application or publisher broke the top 10.

That success is a major reason why Beijing faces growing scrutiny within Europe, explains Gabriela Zanfir-Fortuna, senior counsel for the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF), a Washington-based think tank.

“Until now, Chinese companies did not have a lot of individual users in Europe, or at least the individual users that they had were not very involved with the services,” said Dr. Zanfir-Fortuna, who has worked for the European Data Protection Supervisor in Brussels and leads FPF’s work on European privacy law. “That is not the case anymore with companies like TikTok. I think that is why we have not seen a lot of questions raised by individual users about Chinese surveillance practices until now.”

Europe’s approach to data protection is not just about privacy and human rights, even if those principles are earnestly held. It is also tinctured by political realism.

Europe has thus far failed to produce a homegrown rival to America and China’s tech giants. By developing the strictest data privacy regulation in the world, it has potentially found a way to force China and the United States to play by its rules.

“The EU is caught between the U.S. and China,” said Eline Chivot, a Brussels-based senior analyst at the Center for Data Innovation who focuses on European technology policy. “It sees Schrems and GDPR as a third way to exist in the online environment, not by building large technology companies but by regulating them.”

Dodging the regulators

At present, the most serious risks for Chinese technology companies remain theoretical, and companies will always have the option of fighting back in court.

Having to meet high evidentiary standards is one of the key differences between Europe’s rules-driven approach to technology regulation and the United States’s rule by executive fiat, explains Pádraig Walsh, a Hong Kong-based partner at Tanner DeWitt specializing in technology law and compliance.

“We don’t yet know the full scope of the principles and how they will be applied in respect to Schrems II,” Walsh cautioned. “But if you look at the specific concerns that were expressed by the court in relation to data transfers to the U.S., a lot of the concerns were around what are called the masked surveillance rights of authorities to sweep up personal data being transferred, taking data, for instance, directly from underwater cables.”

America’s surveillance programs were covert and uncontroversial until they weren’t, Walsh points out. So even if European DPAs have good reason to suspect that the CCP is vacuuming up data from companies like TikTok, they might not be able to win cases against them unless there is a Chinese intelligence leak on the order of Edward Snowden’s.

In the interim, companies can take steps to insulate themselves from regulatory risk, including limiting the personal data they collect, localizing that data within Europe, or segmenting business units that operate overseas, as ByteDance did with TikTok and its Chinese counterpart, Douyin.

Implementing those changes will be costly and they still might prove insufficient. Yet they will be necessary to show regulators that companies are taking the EU’s privacy concerns seriously.

TikTok already appears to have taken that cue: at the beginning of the month, it announced it would spend $500 million to build its first European data center.

Another path forward is to delay.

When it was passed in 2018, the GDPR was celebrated for finally giving Europe’s regulators the teeth to punish violators of EU privacy law. But two years later, those provisions have borne little fruit.

By stonewalling Europe’s regulators or threatening to impose costs for aggressive enforcement, China may be able to keep it that way.