What is Double Ten, and why is it significant?

October 10th marks the anniversary of China’s Xinhai Revolution, which toppled the Qing Dynasty and put an end to two millennia of imperial rule. But outside the mainland, commemorations of "Double Ten" are anything but straightforward.

On October 10, 1911, anti-Qing revolutionaries convinced the empire’s modernized army corps stationed in Wuchang (one of Wuhan’s three districts) to join their cause. The uprising quickly gained momentum across the country, and a short two months later, the Republic of China was established, becoming the first globally recognized republic in Asia.

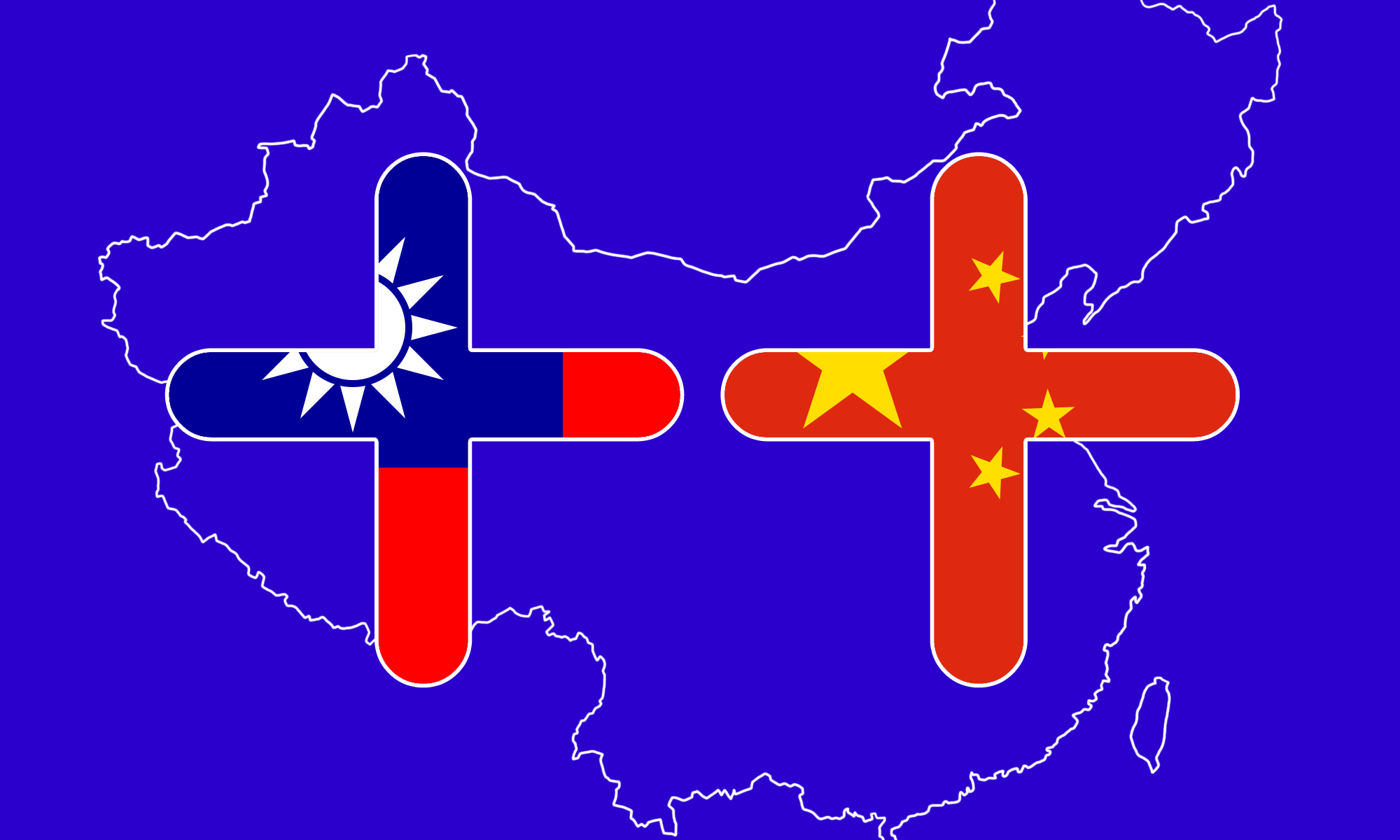

These days, October 10 is the official national day of the Republic of China (ROC), and is widely celebrated as “Double Ten” in Taiwan. But on the mainland, Double Ten passes every year with hardly a blip; instead, the People’s Republic of China commemorates the anniversary of its founding 10 days earlier, on October 1, which kicks off a full week of holiday known as Golden Week.

The holiday, however, is a lot more complicated than just a national day (i.e., July 4th). There are two sets of controversies surrounding Double Ten.

Double Ten in a Chinese Context

After Mao, the Chinese Communist Party has never traditionally been outwardly opposed to the idea of Double Ten as the symbolic birth of modern China. This is because they no longer view the ROC as a legitimate threat to their rule in mainland China. But in the past, the day has given dissenters an opportunity to speak out against Beijing on Weibo, often surreptitiously (link in Chinese).

This year’s Double Ten, however, saw a very different response from the CCP. State media Global Times boasted about how the People’s Liberation Army’s recent high-profile aggression in the Taiwan Strait has weakened Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén) tone in her national day address, while CCTV announced major progress in China’s “Thunder 2020” initiative against Taiwanese espionage. In addition, civil servants were required to watch a special program on state television (CCTV) that featured anti-Taiwan propaganda.

In overseas Chinese communities, however, observing Double Ten is still relevant to their Chinese identity. Manhattan Chinatown in particular is known for its enormous parades that ostentatiously honors the ROC flag. Hong Kong, too, has a proud history of celebrating the holiday. But different from the omnipresent ROC flags that October during the height of the anti-extradition protests, this year’s events were canceled because organizers feared repercussions from Beijing.

A Domestic Debate in Taiwan

Since its formation, Taiwan’s Kuomintang (KMT) party has been very serious about observing Double Ten as a national holiday. For them, it is one of the last existing links to its mainland Chinese roots. Before Taiwan’s democratization, the KMT regime used to hold exuberant military parades on Double Ten, which served as a reminder of its commitment to “take back the mainland”

Meanwhile, supporters of the Hoklo-dominated Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) look at Double Ten in a different light. Many feel that the history behind the holiday is no longer relevant to Taiwan, as the island was under Japanese occupation during the Wuchang uprising. Instead, they view it simply as a day off.

Some of the more radical proponents of Taiwanese independence (“deep green”) see Double Ten as an insult to the Taiwanese identity. They view the ROC as an illegitimate, colonial regime governing Taiwan, no different from the Japanese, Qing, and Dutch empires that came before. This stance is often held by Taiwan’s běnshěngrén (本省人, literally “people of the province”), the descendants of Hoklo or Hakka (cultural subgroups within the Han Chinese) settlers that came to Taiwan before the Japanese occupation in 1895. (They are in contrast to the descendents of those who fled the mainland following the KMT’s loss in the Chinese Civil War.)

“The so-called Taiwan flag is actually the ROC flag,” said Freddy Lim, a member of Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan and founder of the “deep green” New Power Party. “The meaning of that flag is martial law, oppression, and the symbol of the authoritarian KMT… A lot of people like me never go to the flag raising ceremony on October 10th…I just can’t stand those symbols. They are the legacy of an authoritarian regime, and it makes no sense for a democracy like Taiwan to celebrate this event.”

As Taiwan’s younger generations become increasingly invested in an unique Taiwanese national identity, it’s likely that Lim’s stance gains traction in the coming decades.

Meanwhile, the DPP mainstream has been embracing Double Ten as Taiwan’s national day to appeal to a wider pro-ROC voter base. Tsai identified Double Ten as #TaiwanNationalDay on Twitter, which falls in line with her administration’s branding of the island as “Republic of China Taiwan.” Although the DPP might lean more toward Taiwanese independence, they also hesitate to put this to action in fear that abolishing the ROC would leave them vulnerable to military action from Beijing.