Fried rice backlash: Why Chinese internet users turned on a celebrity chef

Chef Wang has millions of followers on social media because of his straightforward, no-nonsense approach to cooking. He is not political. But that doesn’t mean he can’t be accused of politics — as he recently found out when one of his dishes reminded viewers of the death of Mao Zedong’s son.

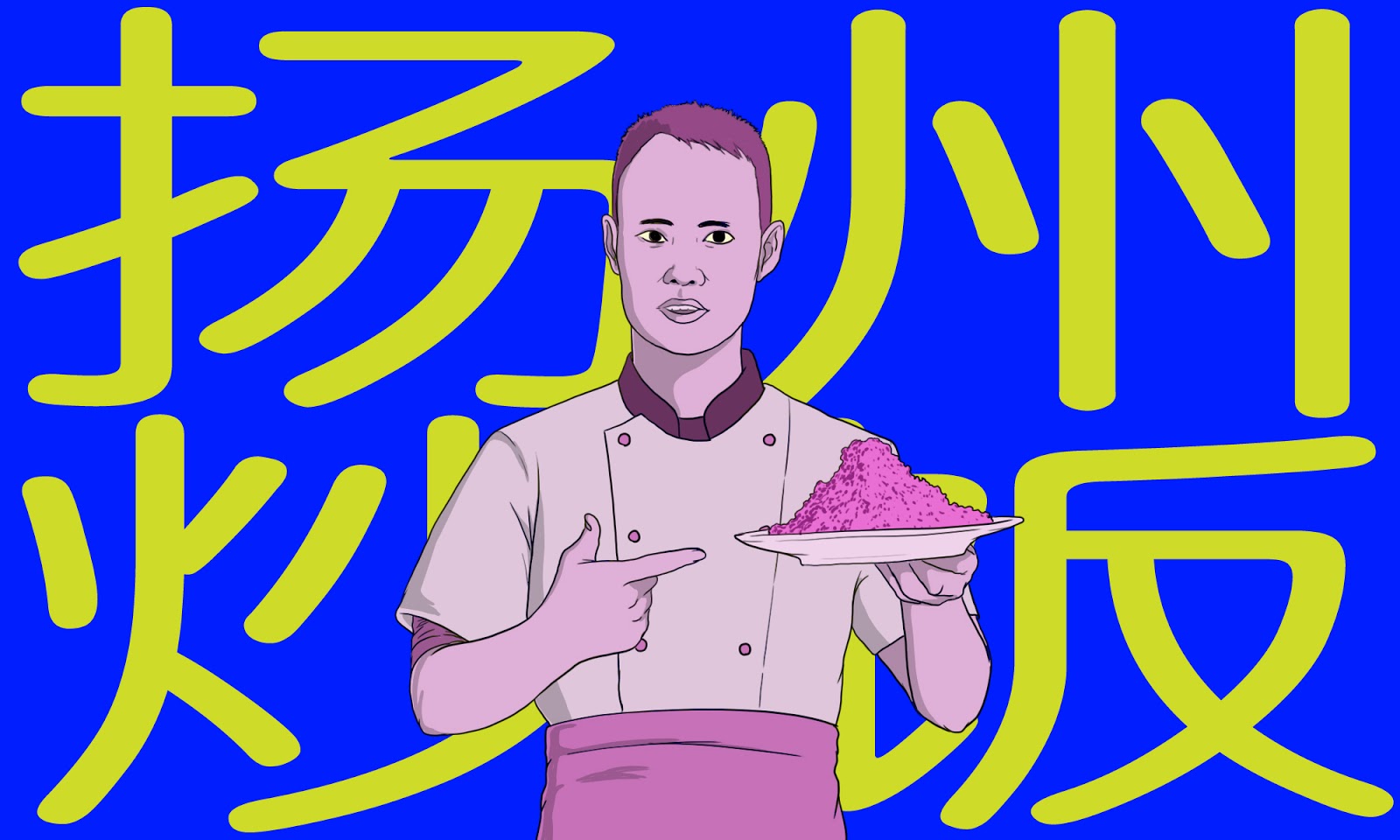

Wáng Gāng 王刚, better known online as Chef Wang (美食作家王刚), is a celebrity Sichuanese chef who has tens of millions of followers on YouTube, Bilibili, and Weibo. He is known for his stoic, no-B.S. style that introduces dazzling restaurant-quality techniques and practices, rather than relying on personal anecdotes, humor, or cultural elements, like many other cooking channels. Many of his fans admit that because his dishes are too complicated for most home cooks, they watch simply to marvel at his skills and professionalism.

Wang’s content is not at all political, and he’s so non-offensive that his channel has become one of the rare “middle grounds” where both Chinese and Taiwanese online users can meme together without getting offended.

At least, that was the case until two weeks ago.

On October 24, Wang uploaded a video about how to make authentic Yangzhou-style fried rice. While most of the comments on his YouTube video were meme-like references to Uncle Roger (a Malaysian comedian who playfully skewered a BBC host’s sacrilegious way of making fried rice), one significant part of his viewers on the Chinese internet accused him of “humiliating China” (辱华 rǔ huá, which has become quite a buzzword in the past five years).

How did fried rice, one of China’s most recognizable cultural icons, “humiliate China?”

It was a matter of timing.

October 24 is the birthday of Máo Ànyīng 毛岸英, Mao’s presumptive successor, and his death involves…egg fried rice. It’s an apocryphal story, but here’s how it goes: according to General Yáng Dí’s 杨迪 memoir on his experience during the Korean War, Mao Jr. broke air defense protocols and cooked egg fried rice in the Chinese HQ, the smoke of which attracted a U.S. bombing that ended up taking his life. It is widely believed that Péng Déhuái’s 彭德怀 fall from grace in 1959 had a lot to do with his failure to keep Mao’s heir safe.

Many in China were actually glad that Mao Jr. never made it home. If he became Mao’s successor, it’s uncertain whether the country would have enacted the sort of economic reforms that allowed it to escape North Korea’s fate. In fact, November 25 — the anniversary of Mao Jr.’s death — has been celebrated as “Chinese Thanksgiving.”

#巴丢草 漫画 【蛋炒饭】一碗腊肉蛋炒饭,浓浓的爱,深深的情,请各位推友笑纳!#毛岸英 #毛泽东 #蛋炒饭 pic.twitter.com/WnNz8gAcGz

— 巴丢草 Bad ї ucao (@badiucao) November 25, 2015

Chef Wang, who has shown no indication that he was aware of any of this, was accused of using his video as “malicious political innuendo” (恶毒的政治隐喻 èdú de zhèngzhì yǐnyù) that tarnishes Mao Jr.’s image as a “revolutionary martyr.” This was not the first time that Wang has unexpectedly found himself mired in controversy. In the past, he has been criticized for animal cruelty and using visceral images of butchering (it is a tradition in the Chinese restaurant business for most of the butchering to be done in-house). Most notably, his video on braised salamander came under fire when it was suspected to have broken China’s wild animal protection laws, though he later clarified that the salamander he used in the video was farm-raised. This time, however, Wang wouldn’t be saved by “cultural differences.”

Fortunately for Wang, an unlikely ally rushed to his defense. State media feared that this controversy would inadvertently publicize the rumor in question — that Mao Jr.’s death was due to a fried rice craving. “The connection between martyr Mao Anying and egg fried rice was a rumor in the first place, and it was fading away with time,” wrote an analyst at Guancha.cn. “Isn’t it a good thing that less people know about this rumor?”

The nationalist fervor that followed Xi’s provocative speech on the 70th anniversary of China’s intervention in the Korean War adds another layer of significance to this year’s “Egg-fried Rice Festival.” When the party-state can no longer be challenged by any form of protest, humor becomes the last refuge for defiance. Noted Australian sinologist Geremie Barmé remarked on his site China Heritage that people are getting especially creative with their celebrations:

One quick-witted commentator suggested that another popular egg-and-rice dish should be included in the festival: 親子丼 oyako domburi (qīnzǐ dǎn in Standard Chinese), or “parent-and-child rice bowl” consisting of fried chicken and scrambled egg over rice. The dish, it was suggested, neatly accommodated both Mao Anying and his father. Then, in consideration of the Maos’ Hunanese origins, some suggested that it might be more appropriate for the festival to feature another father-son dish: “Smoked Pork Egg-fried Rice” 臘肉蛋炒飯 làròu dàn chǎo fàn, with Mao père represented by Hunan-style smoked pork 臘肉 làròu.

Perhaps a nice addition to the menu would be Hainan drunken chicken (海南醉鸡 Hǎinán zuì jī), a portmanteau of “Hainanese chicken rice” and “Shanghai drunken chicken,” phonetically spinning off the Hainan Island incident (海南撞机事件 Hǎinán zhuàng jī shìjiàn) in 2001, involving the collision between a U.S. spy plane and Chinese jet, which has become another one of China’s nationalist dog whistles of late.