Our future tech dystopia begins in China

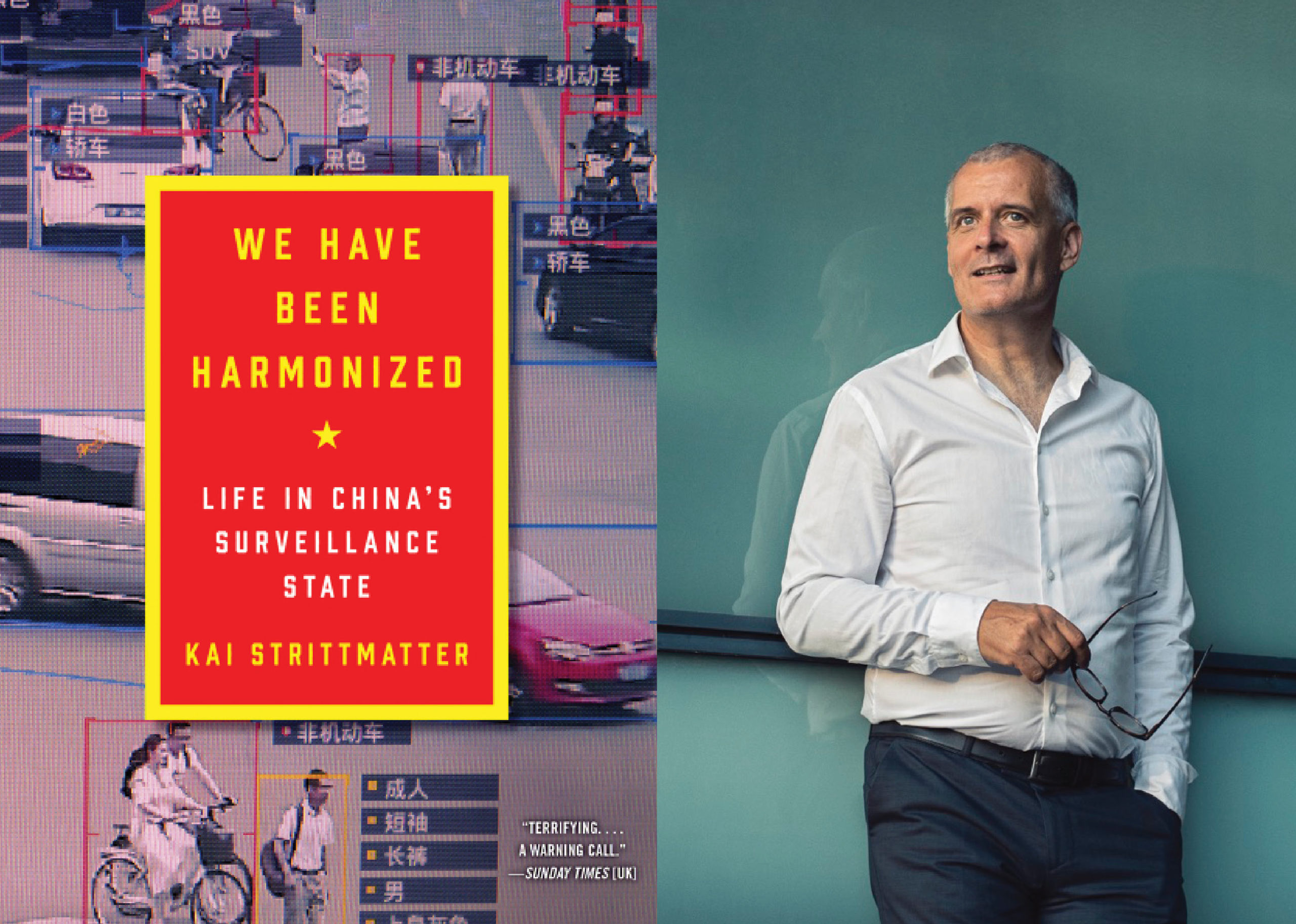

Kai Strittmatter's recent book, "We Have Been Harmonized: Life in China’s Surveillance State," examines how the Chinese government is using technology to censor, surveil, and control its population. Does it read like a warning, or merely a glimpse of what awaits us all?

“Don’t read the newspaper. Look at our website, it’s much more interesting,” a journalist at a Chinese state newspaper once told me excitedly in the late 1990s. In those early days of the internet in China, the web seemed to offer infinite possibilities of space and openness — even to state media reporters. And during the early years of Sina Weibo, a microblog akin to Twitter but with more functions, it seemed “the free world had fallen into citizens’ laps,” writes Kai Strittmatter in his book We Have Been Harmonized: Life in China’s Surveillance State. “Citizens learned to pool their knowledge, to have public discussions…For the first time, people felt that they belonged to a society that deserves the name.”

But the majority of Strittmatter’s book focuses on what happened next — how, after Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 became Communist Party leader in 2012, he “took on a diverse, lively, sometimes insubordinate society and did everything in his power to ‘harmonize’ it…[and] wasted no time in showing the world how one goes about taming the internet,” largely through arrests and anti-rumor laws. These days, Strittmatter writes, the Party no longer fears the power of social media; in fact, it has “learned to love the internet and new technologies.”

Through data from apps, surveillance cameras, facial and voice recognition technology, and artificial intelligence, backed by massive state investment and support, China is now seeking “to create the most perfect surveillance state the world has ever seen.” Not content with “reinventing dictatorship for the information age,” Strittmatter argues that the Party is also exporting the technology for this “new operating system” to governments worldwide. Beijing, he says, is “making the world safe for autocracy.

“The greatest challenge to liberal democracy will come not from a stagnant Russia. It will come from the economic powerhouse of China.”

Strittmatter first studied Chinese in the 1980s — we were students together in Xi’an from 1986-87 — before becoming Beijing correspondent for Germany’s Sueddeutsche Zeitung from 1997 to 2005. He returned to China for another posting in 2012, just in time to observe how, under Xi, the Party began to reintroduce ideology, root out foreign ideas, and attempt to “creep back into every crack of people’s lives.”

But he also reserves criticism for the international community, which he says has been slow to respond to China’s efforts to influence international values, whether in the field of education, in multilateral organizations, or in its attempts to set new rules for cyberspace. He notes Beijing’s growing influence over countries of eastern and southern Europe, which it funds through the “17+1” grouping. Such ties have given Beijing huge influence in the EU. “With Hungary and Greece, China is now practically sitting round the table in Brussels.”

Strittmatter was inspired to write We Have Been Harmonized on the day of Donald Trump’s election in 2016, fearing that the international community’s credibility, and willingness to resist Beijing’s attempts to challenge global norms, would be undermined by America’s new leader. With his experience working in Turkey as well as China, Strittmatter says he saw, in the words of Trump and other Western populists, echoes of the way authoritarian systems manipulate language and minds, and wanted to sound a warning about “the return of autocrats and would-be autocrats, and the shameless lie as an instrument of control.”

“We want to give the city eyes. And we want to make them intelligent.”

The core of the book is an investigation into the new surveillance technologies being rolled out in a nation whose fast-growing national police camera network can reportedly identify any one of China’s 1.4 billion citizens within a second. Strittmatter quotes former Google CEO Eric Schmidt as saying that China will “dominate” the global AI industry by 2030. Strittmatter details police plans to employ biometric identification technologies and “intelligent surveillance, early-warning and control systems,” which the authorities say will allow them to “grasp group cognition and psychological changes in a timely manner,” and “know in advance who might be planning something bad.”

“All the things you’ve seen in science fiction films — we’re going to make them a reality…We want to give the city eyes. And we want to make them intelligent,” the marketing director of facial recognition developer Megvii Face++ tells him, adding, reassuringly, that “all the data is stored with the police. It’s quite safe there.” At rival firm SenseTime, Strittmatter hears that its cameras and AI can predict when crowds are about to gather — and flag anyone moving against the flow in a group of people as “abnormal.” And at China’s biggest voice recognition company, iFlyTek — which runs call centers for major mobile phone operators and works with the police on “keyword-spotting technology for public security and national defense” — he is told that, with its easy access to big data, “China is the Wild West right now. A test laboratory.”

Several of the companies he visits are now on the U.S. government’s entity list, restricting their ability to trade in the U.S., mainly because of their involvement in Xinjiang, the real “wild west” of China’s cyber surveillance state. Strittmatter describes how compulsory apps, which provide the authorities with access to data from the phones of all the region’s residents, and an integrated AI platform that allows facial recognition scans at street checkpoints, have helped create what scholar Adrian Zenz calls a “high-tech version of the Cultural Revolution” in Xinjiang. Indeed, Strittmatter suggests some people have been interned there based on decisions made purely by artificial intelligence software, since “police officers don’t check each individual case.”

And Strittmatter describes Xinjiang as a “testing ground” for AI technology that could be rolled out elsewhere. Members of the Communist Youth League around China, for example, already have their phone usage data uploaded to a “Smart Red Cloud,” which tracks cadres’ actions and relationships to predict “their future ideas and behavior.”

In the Shandong city of Rongcheng, Strittmatter visits one of the smart “social credit” schemes currently being piloted in several dozen Chinese cities: he is enthusiastically informed that it has led to residents filming each other’s misdemeanors, and that anyone who petitions a government department will be put in the system’s lowest category, making it hard for them to access credit and even use public transport or get their children into good schools. The pace of the rollout of these schemes nationally remains uncertain, yet they clearly fit with an approach in which people are seen as “walking sets of data” — boosted by the world’s highest rate of smartphone transactions. It’s notable that an advisor to the social credit scheme, a professor at Peking University, tells Strittmatter that a central national database for the scheme could be “dangerous” in terms of its implications for citizens’ privacy — yet he also stresses how “excited” he is to be involved in this pioneering project.

“You can’t even ask certain questions: they lie outside your realm of experience and powers of imagination.”

One of the aims of such scrutiny is to ensure that citizens ‘internalize’ the party’s control, leading them to self-censor, Strittmatter suggests. Now, Party members must download an app for studying Xi Jinping theory, which “registers every minute you devote to something and every paragraph you read.” Combined with a revival of ideological slogans and “the mix of nationalism, siege mentality and dreams of superpower status pumped into the people by the propaganda machine,” Strittmatter argues that this can create what People’s Daily calls a “‘firewall’ in our brains,” leading citizens to reject information that does not fit the official line.

According to sociologist Sūn Lìpíng 孙立平, such internalization means “you can’t even ask certain questions: they lie outside your realm of experience and powers of imagination.” While some people use VPNs to get around restrictions, one Beijing high school teacher in his late 20s tells Strittmatter that his “incredibly tech-savvy” students only evade censorship “for entertainment, to follow celebrities,” making no effort to seek out foreign news reports. When they see different versions of Chinese history from foreign sources, “they look at me helplessly,” he says. “Their thinking isn’t joined up anymore, they don’t have any background knowledge…They ignore reality; it’s been made easy for them.”

It’s a reminder of the difference between many of today’s young generation and those who grew up in the age of the more open internet, before 2013. Strittmatter’s account is, in a sense, a lament for what he calls the “Weibo era” — a time when “people started thinking about things…There was an awakening: individual, political, aesthetic, cultural,” as the writer Murong Xuecun, one of many cultural figures interviewed in the book, puts it.

Now, with its combination of tight online censorship and proliferation of lively entertainment, gaming, and commercial platforms, Strittmatter sees China moving toward “an outwardly colorful mix of George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, where people devote themselves to commerce and pleasure and in so doing submit to surveillance of their own accord.”

The one occasion in recent years when the Party’s grip on online debate slipped significantly was earlier this year, at the beginning of the COVID crisis, when it emerged that Wuhan officials initially failed to take prompt action against the virus, and local doctor Lǐ Wénliàng 李文亮 had been admonished by police after warning colleagues about a new SARS-like virus in a chat group. When Dr. Li himself died from the disease, Chinese social media lit up with defiant criticism of the government and calls for greater freedom of speech, in what felt like a throwback to the pre-2013 era.

Yet for all the talk outside China that this would turn out to be the regime’s “Chernobyl moment,” the Party’s position soon began to look far more secure. It achieved this in part by “censorship, propaganda, repression,” Strittmatter writes, detaining citizen journalists and other critics, while declaring “total victory” over the virus and honoring the late Dr Li as a martyr. The tight restrictions introduced in Chinese cities did seem to control the virus fairly quickly, however, and the shambolic response of some Western governments aroused scorn and disbelief in China. Of Donald Trump’s handling of the pandemic, Strittmatter says “the Communist Party could not have wished for a better partner in its plan to make its own sins forgotten.”

But the outburst over Dr. Li’s death made it clear that even the would-be perfect surveillance state has not yet crushed all independent thought in China — and that there are still risks inherent in extreme levels of control. Yet Strittmatter notes that many in China willingly downloaded official health code apps during the pandemic, thus boosting “the normalization of high-tech surveillance by tracking tools” in the country. His timely book, vividly written and excellently translated from the German by Ruth Martin, is a reminder of where this could lead.