12 hours outside Haidian People’s Court: China’s landmark #MeToo case

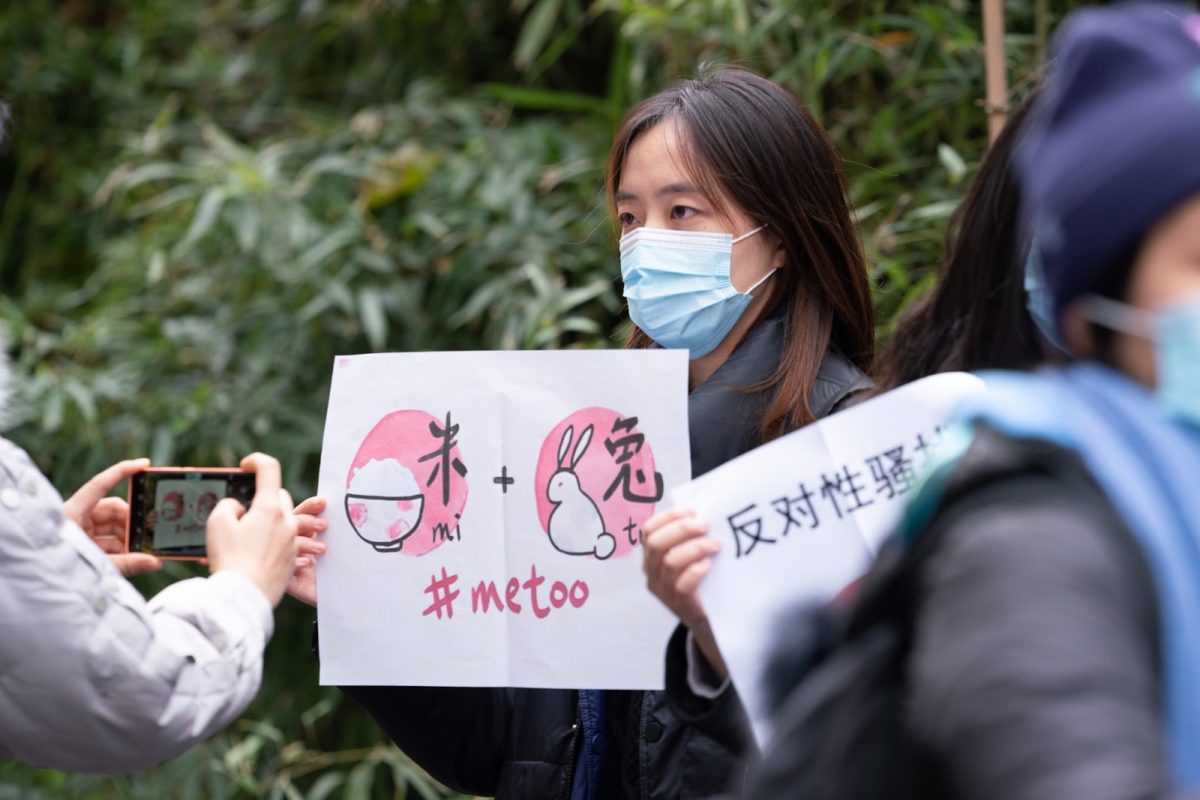

A diverse crowd gathered outside a Beijing courthouse last Wednesday to offer support for Xianzi before her sexual harassment trial against state TV host Zhu Jun. “She has been an inspiration for so many people,” one supporter said.

When 21-year-old Sicheng arrived with his friends at Haidian People’s Court in the late morning on December 2, small clusters of people were already there, quiet and watchful. He could sense the nervous anticipation of the people present — most of them young people much like himself. They were all there for Xiánzǐ 弦子 (who has not revealed the characters of her Chinese name), the young woman who two years ago filed a sexual misconduct case against the well-known TV host Zhū Jūn 朱军 — and along the way became the face of China’s #MeToo movement.

The crowd of supporters gradually swelled to about 100 people by midday, though a larger group of onlookers eventually merged with these supporters, making the crowd seem much bigger.

Sicheng reached inside his canvas bag and pulled out a sign made out of cardboard, reading #MeToo. He hesitated briefly, but dozens of other signs and posters, handcrafted or printed, were already out on display.

On one part of the street, 10 people each held a piece of paper with one Chinese character on it, reading: “Together we ask for an answer from history” (我们一起向历史要答案 wǒ men yī qǐ xiàng lì shǐ yào dá àn).

To Sicheng and many others, Xianzi is far more than just a sexual assault survivor. On Weibo, Xianzi has leveraged her influence for the benefit of the voiceless.

“It’s touching to witness her growth and see her become a force for cohesion in various social movements,” Sicheng said. “She has been an inspiration for so many people, including me, so I feel obliged to be present at this momentous occasion.”

The crowd kept growing as cameras clicked away. Around 12:50 p.m., shouts from police officers came from a booth at the entrance of the courthouse. They looked underprepared for the scene unfolding before them, grunting into walkie-talkies.

Xianzi’s supporters were a diverse crowd. A young female student came by train from several provinces away; a marketing associate took leave from a local translation firm to be here; and a middle-aged man in a leather jacket said he was here for his daughter. “My daughter has gone through similar things,” he said. “In China, things like this usually go unspoken.”

Another young man said he was here for what Xianzi has done for the LGBTQ community. “She has been an ally to minority groups along the way,” he said. A week before her trial, Xianzi was promoting a transgender awareness campaign held by the Beijing LGBT Center on Weibo — just one of several social issues Xianzi actively engages in.

Three minutes before 1 p.m., someone called out, “Xianzi! Xianzi is coming!” A circle quickly formed.

“Is that her?” a girl asked, pushing through the crowd.

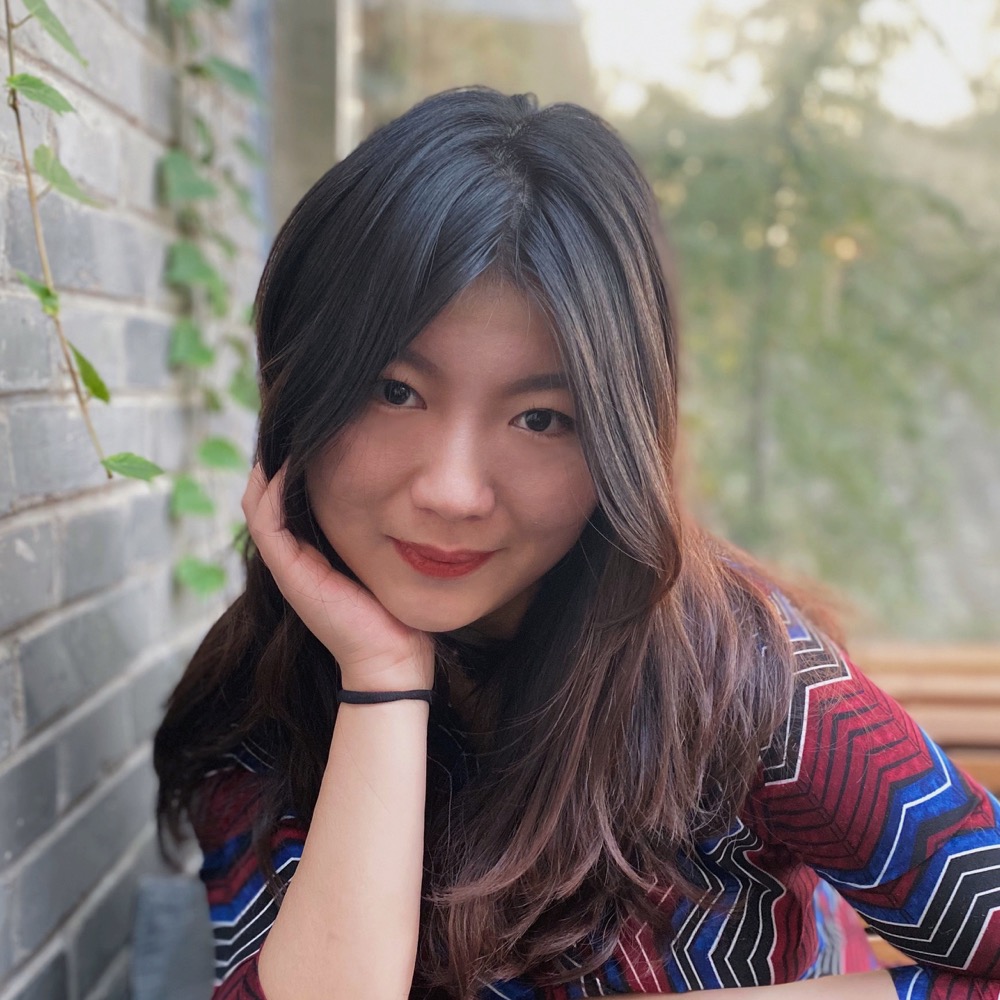

Despite being generous with media appearances since 2018, Xianzi can still blend into any crowd. She is 27 now, a screenwriter living in Beijing with her boyfriend. It’s been two years since her Weibo post — in which she details being groped by Zhu Jun in a dressing room in 2014 — went viral.

Xianzi, accompanied by three friends, wore a beige overcoat, scarf, and white pants. Hearing shouts of encouragement, she briefly looked like she was close to tears, but her expression quickly changed to one of gentle determination. She stopped in the center of the crowd, then cleared her voice. “I hope my case will help progress China’s legal system. Whether we’re successful or not, I hope you won’t be too disappointed,” she said. “Even if we don’t win the case, we will leave an urgent question for people to come.”

Someone tossed her a scroll, which Xianzi caught almost out of instinct. “Must win” (必胜 bì shèng), it read, the two characters written in bold strokes in the fashion of traditional Chinese calligraphy. It was reminiscent of a scene last December in which Japanese journalist Shiori Ito walked out of her courthouse with a scroll reading “case won” after she won her rape case.

The crowd cheered Xianzi into the courthouse. The trial was to be a private one, though both Xianzi and Zhu Jun petitioned for it to be public. (The trial was adjourned just before midnight without a verdict, though it will continue at another time; Zhu never showed up.)

Across from the courthouse, another wave of demonstrations began. Two young women wrote “Me2” on each other’s masks, which led others to do the same.

“The Me Too movement started early in the United States, but it didn’t make any big progress in China until Xianzi paved the way,” one supporter said. “Xianzi has everyone’s backing, and has inspired many people to support women.”

“This case is special because Zhu Jun is such a high-profile powerful figure, and that’s why pushing this case forward can be extremely difficult,” said Alex, a content creator. “I am very worried about Zhu’s absence and the fact that the trial is taking place out of the public’s eyes.”

Meanwhile, police began to operate with heightened vigilance. On an adjacent street corner, at least six police cars idled. Amongst the crowd, police began to ask supporters to jot down their personal information. “You can take pictures, but if someone’s picture on social media gets taken out of context and used by people with ulterior motives, you will be liable,” one officer said. “The police can find you wherever you are.”

In the afternoon, Caijing became the first and only mainstream Chinese media outlet to report on the case. On WeChat, six group chats put together by activists Liáng Xiǎomén 梁小门, Dà Tù 大兔, and Xiào Měilì 肖美丽 — each filled to its maximum of 500 people — provided updates in real time.

Many people followed the case through their WeChat Moments, which is akin to Facebook’s News Feed. In China, where large-scale, spontaneous public events are rarely seen, the fact that the public was able to see uncensored images on WeChat is noteworthy. (On Weibo, on the other hand, posts about the gathering were deleted quickly after publication.)

“I felt present at the event, just through the power of the internet,” said Jingyi, a tech reporter who was invited to the WeChat group “Friends supporting Xianzi No. 2.” Jingyi said she spent the majority of the afternoon scrolling through for live updates.

Camaraderie formed in these groups. People organized for food and bubble tea to be ordered and delivered to outside the court. Meanwhile, censored articles were archived on Github.

“At the end of the day, what got me crying was the strength of the community,” said Xu Meijing, who was at the scene. “Xianzi and her friends are a source of courage wherever they are. That we were able to gather and peaceably demonstrate for over 10 hours is a miracle, and it was our shared vulnerability that got us together.”