Year in Review: 2020’s biggest news stories about Chinese women

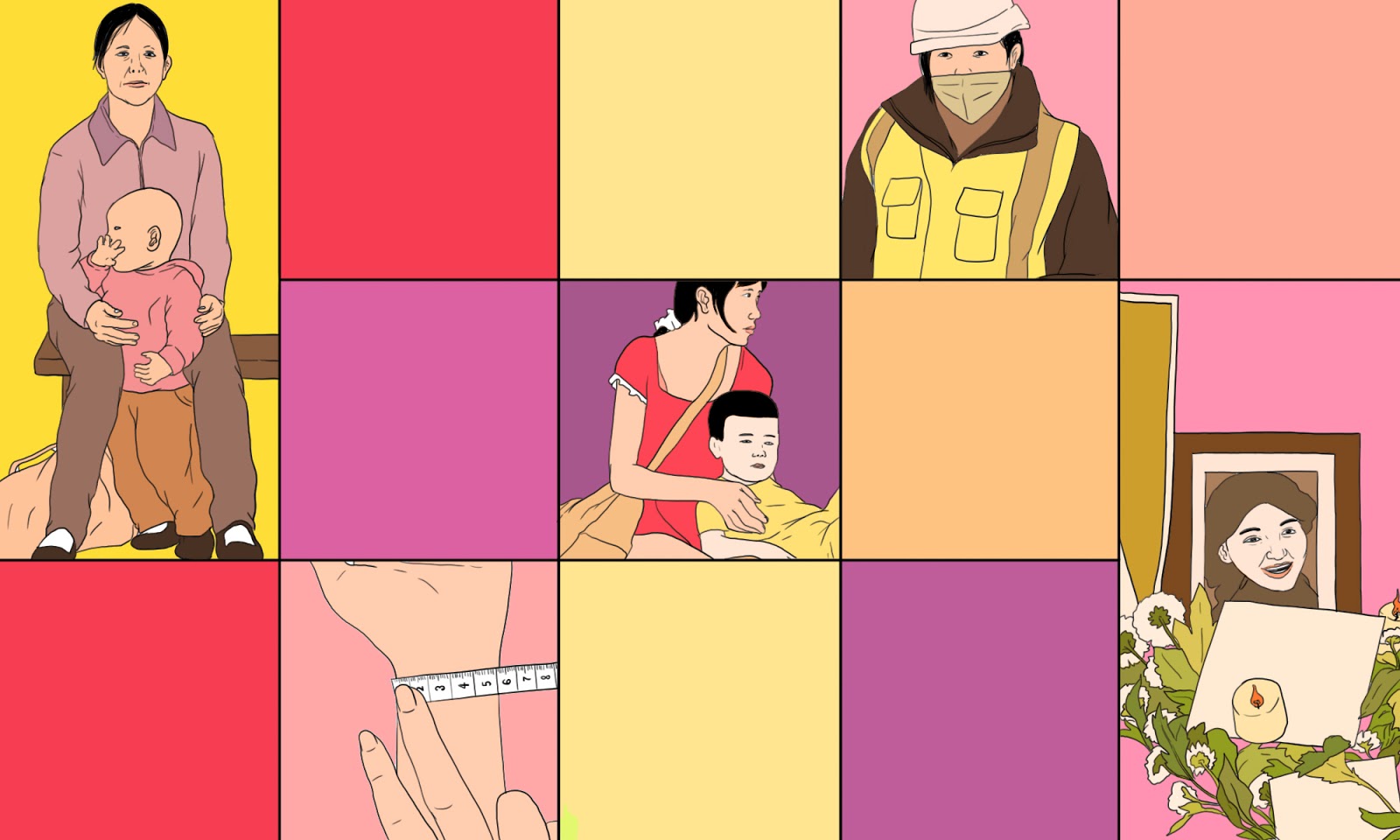

In a year defined by crisis, Chinese women found their urgent voices — demanding changes to the policies that affect their lives, smashing taboos, uniting to end violence against women, refusing to conform, and calling out misogyny whenever and wherever possible.

In times of trouble, uncertainty, and despair, people tend to turn inward while searching for a sense of community and a meaningful cause to fight for.

For Chinese women, 2020 was one of those years: As the COVID-19 pandemic upended the country, they found their urgent voices — demanding changes to the policies that affect their lives, smashing taboos, uniting to end violence against women, refusing to conform, and calling out misogyny whenever and wherever possible.

But 2020 also presented its fair share of hardships and obstacles for Chinese women in their quest for respect and equality.

Here are some of the major events — some good, some bad — that have shaped the current situation of Chinese women this past year.

1. Xianzi’s landmark #MeToo case got its day in court

The long-anticipated lawsuit against Zhū Jūn 朱军, a powerful Chinese media figure who was accused of sexual harassment by a former intern, opened in a Beijing court in December. Many view the case as a test of the #MeToo movement’s durability in China — a sexually conservative society where gender inequality is still deeply entrenched and women’s voices are routinely discounted.

The plantiff, Zhou Xiaoxuan (she has not revealed the Chinese characters of her name but is known in China by her nickname Xiánzǐ 弦子), is a 27-year-old screenwriter who came forward in 2018 with sexual assault allegations against Zhu.

After more than 10 hours of testimony, the court adjourned around midnight on December 2 without announcing a ruling. Zhou said that she and her lawyers had submitted several requests at the end of the hearing, including for an open hearing, a change of judges, the jury’s participation, and Zhu’s presence at the next hearing, but the court has not set a date for the trial to resume.

The initial hearing saw a diverse crowd of supporters for Zhou gathering outside the courthouse, chanting and holding posters. And despite the lack of coverage of this news in Chinese media, social media users demonstrated a heightened awareness of the issue and an eagerness to hold Zhu accountable in the court of public opinion.

Since the #MeToo movement took hold in China in 2018, a string of cases featuring all manner of harassment and assault have been brought to the forefront of the public consciousness. While China’s new Civil Code, for the first time in Chinese history, recognizes sexual harassment as a legal cause of action, only a few men — a tiny proportion of men who have assaulted and harassed women — have faced legal consequences for their actions.

2. Women called out media for sexist COVID-19 coverage

The COVID-19 crisis has brought a host of long-standing issues to the fore. One of them is the persistent lack of women’s voices in the media, a problem that has become more acute than ever as Chinese news articles about the pandemic rarely feature women experts, female doctors and medical workers, and women protagonists in general.

In February, as the virus raged across the country, Chinese news outlets produced a deluge of articles singing the praises of brave workers and health professionals combating the outbreak. However, Weibo user @马库斯说 (mǎkùsīshuō), an outspoken feminist on Chinese social media, pointed out in a viral post that overall coverage appeared to be sexist and misogynist. In a shockingly outrageous example, a popular video uploaded on Bilibili features a group of construction workers who built China’s first pop-up medical facility for COVID-19, and none of them is a woman.

“I’ve seen photos of women engineers, women construction workers, and women designers who spent time on this project,” @马库斯说 wrote. “But if the content we are consuming now is all like this, I’m afraid that some truth would get lost after years go by. Will people still remember the contribution these women made in this battle in the future?”

Inspired by the activist’s complaint, hundreds of thousands of people passionately joined in an online campaign to raise recognition of women in the national battle against the deadly virus. Congregating around the hashtag “Women workers need to be seen” (#看见女性劳动者# kànjiàn nǚxìng láodòngzhě), a coalition of Weibo users shared stories of women from different walks of life who deserved more attention during the outbreak while urging media outlets to end the marginalization of women in reporting of the coronavirus.

3. Student activists campaigned to end period poverty

In August, a conversation about period poverty — the inaccessibility of feminine hygiene products, especially for low-income women — erupted on Chinese social media following a viral post that revealed the existence of dangerously low-quality, brandless, and package-free sanitary pads.

Inspired by the conversation, a group of students and teachers launched a nationwide program setting up dispensers of free sanitary pads outside bathrooms in over 300 schools and universities. Spearheaded by the gender advocacy group Stand by Her, the grassroots campaign was part of a broader effort to fill the gaps in the menstrual health space, and to remove the stigma surrounding a natural biological process that Chinese women have long been taught to hide and be ashamed of, according to its organizers.

4. Body positivity entered mainstream parlance

This year, the body-positivity movement, once on the fringe, has gone mainstream in China thanks to an increasing number of Chinese women who started to feel comfortable in their own skin despite deeply rooted social pressures to conform and maintain a certain type of body shape. As the positive message of self-love and body acceptance found a growing audience on Chinese social media, celebrities who promoted unrealistic beauty standards were called out, businesses that insulted plus-size bodies were criticized, and beauty fads that encouraged women to show off their slim figures were met with intense resistance.

5. China still failed victims of domestic violence

Lhamo 拉姆, a Tibetan woman who ran a popular video blog on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, was fatally attacked at her home in mid-September. Police have arrested her ex-husband on charges of murder.

The story is tragically familiar: Lhamo tried repeatedly to protect herself and her two children from her abusive partner. She divorced him, remarried him under threat of harassment, and divorced him again due to his violent behavior. She called the police multiple times when assaults occurred, but her complaints weren’t taken seriously and she never received the protection she sought.

Then, on the evening of September 14, when she was livestreaming from her kitchen, the man she had divorced less than three months previously broke into her house, doused her with gasoline, and set her on fire with a lighter. About two weeks later, she died from the severe burns, which covered almost 90% of her body.

The brutal killing of Lhamo was one of the several high-profile domestic violence cases that occurred this year and triggered an outpouring of indignation in China. Back in July, a horrific video of a husband beating his wife before she jumped out of a second-story window to escape the violence gained a tremendous amount of traction on Chinese social media. When speaking to the media, the battered woman revealed that because a local court refused to grant her a divorce, she was still stuck in her abusive marriage almost a year after the desperate leap.

In China, violence against Chinese women, specifically intimate partner abuse, has long been a pervasive problem that typically goes underreported in the media and unjustly treated by the law enforcement agencies. The severity and urgency of the issue is perfectly encapsulated in “Xiao Juan” (小娟 xiǎojuān), a Mandopop song released by Chinese singer Tán Wéiwéi 谭维维 in December. A rage-induced, powerful anthem, the song features the progressive artist critiquing the mistreatment of the victims and the lack of repercussions for their perpetrators, all while telling specific stories of women being assaulted by “fists, gasoline, and sulfuric acid.”

The situation has been particularly dire this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic. As reported by Chinese media, as more people had to stay at home, more victims of domestic violence were locked in with their abusers, and many domestic abuse support services had to limit their efforts because of COVID-related financial constraints.

6. New law requiring 30-day cooling-off period before divorce sparked anger

In May, China passed its first-ever Civil Code, which contains a new clause requiring divorce-seeking couples to wait 30 days before their requests can be processed.

Since the idea of a “divorce cooling-off period” was first introduced to the public in 2019, it has met fierce opposition from critics who argue that the legislation does nothing but place unnecessary barriers in front of people who are in dire need of a divorce, especially women facing violent domestic abuse.

The controversial law was a long time in the making. In a bid to reduce the country’s soaring divorce rate, local officials in China have — for years — directly intervened in hopes of mending marriages, mainly by creating administrative obstacles and denying divorce petitions for arbitrary reasons.

7. Female celebrities proudly embraced childlessness and singleness

In China, where traditional values — and new Communist Party campaigns — dictate that women’s first and foremost duty is to procreate, there’s a lingering stigma surrounding single, childless women, who are constantly judged by society for their supposed selfishness and self-absorption.

Luckily, this year has seen some women celebrities — such as Chinese actress Qín Lán 秦岚 and internationally acclaimed dancer Yáng Lìpíng 杨丽萍 — using their platforms to speak up about their decision to skip out on motherhood and help shift the cultural expectation.