Some of Us Did Not Die

Two decades after first encounter, Yangyang Cheng revisits The Lord of the Rings trilogy and explores new lessons about state power, climate crisis, exile, and allegiance.

Staying up overnight, when one manages to and does so by choice, is a magnificently empowering experience. You watch the world fall asleep. You are there when it wakes up. The hours between midnight and first light feel like stolen time, laws of physics and biology defied.

On the last night of 2020, I decide to rewatch The Lord of the Rings.

I first encountered the enchanted kingdoms of J. R. R. Tolkien as a young child in China, when one day, my mother brought home a hardcover collection titled World Children’s Literature. “World” meant western. I devoured the pages in the following weeks, forming imaginary bonds with Pippi Longstocking and Karlsson-on-the-Roof. My favorite stories in the series were the two wordiest, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. This was the late 1990s. No one in my family or at school had heard of Frodo or the Dark Lord. I wrote about the ring and its corrupting power for composition homework, and felt both morally and culturally superior.

A few years after, billboards for the movie adaptation would spring up across the city. Aragorn flashed his sword next to newly opened shopping malls and glistening office buildings. Every bookstore stacked Tolkien’s volumes by its entrance. Signs on the windows read: “The first complete Chinese translation.” I knew what I had was an abridged version, but by middle school, all leisure reading had given way to coursework.

When I found a disc set for the trilogy at a street vendor with dubious licensing, my mother made an exception. If the subtitles were turned off, she figured, the dialogues in English could count as language learning. I watched them twice before she decided I was having too much fun. Those steaming summer afternoons appear as vividly as yesterday: the ceiling fan buzzing, the battle for Middle Earth raging in the living room. My mother still lives in the same apartment. She tells me about changes in the city: “You won’t recognize it when you come back.”

At university, a dormmate had a poster of Aragorn glued next to her pillow. Many a night, long past mandatory lights-out at 11:30 p.m., we lay in our bunk beds and debated the attractiveness of the characters. Ranking Aragorn above Legolas was a marker of maturity. I wonder whose face adorns those walls now, who are the latest stars girls giggle about before they sleep.

I came to the U.S. for graduate school in 2009. A boy in my program looked like a dark-haired kin to Merry and Pippin, a fact I wasted no time in pointing out. His name was Sam.

“Are you calling me short, Yangyang?” Sam looked up and asked, feigning indignation. Then, tilting his head back and squinting his eyes, he pronounced with absolute pride, “Samwise the brave.” His thick, curly locks bounced with each syllable.

Sam and I worked on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s most powerful circular accelerator. “One ring to rule them all” was almost a cliche. Before exams and thesis defenses, we avoided references to Gandalf. “You shall not pass” was too unnerving an utterance.

The last time I saw Sam was in the summer of 2019, at a dark matter conference. We had graduated years before and moved to different institutions. We were still working on the LHC. He still looked like a hobbit.

On the last work day of 2019, a colleague asked if we had any New Year’s resolutions. “To survive,” I said. Everyone laughed; only I was not joking. I knew 2020 would be difficult, with the election, rising tensions between my birth country and my adopted home, and the tenuous relationships I have with both governments. I did not know then that a mysterious pneumonia had appeared in Wuhan. In a few short weeks, survival would become painstakingly literal.

I sit at my desk and stare at my screen, a spot I’ve barely left for over nine months. In China it’s already morning on New Year’s Day. I consider calling my mother, but decide to put it off till the date has shifted for me. I dim the lights and press play. Galadriel’s voice emerges from the darkness: “The world has changed. I feel it in the water. I feel it in the earth. I smell it in the air.”

I know the plot well, so there’s no anxiety of anticipation. I suspend judgment and sink into the universe of Tolkien’s creation, richly rendered by Peter Jackson and his crew. It’s a world of tradition, where every creature has its place. The hierarchies and moral codes of Middle Earth mirror our own, but unlike the reality we inhabit, in fantasy friends are loyal, people are brave, the once and future king is wise and good. The gorgeously-realized cinematic universe grants its viewers absolution. The length magnifies the indulgence.

An alliance of elves and men are fighting against Saruman’s army when the clock strikes twelve. I hit pause and look out the window. Fireworks are blooming on the horizon. I take a deep breath and return to the film. I obsessively check the number of hours remaining. I’m not ready to depart Middle Earth. If only time could stand still.

As Frodo and his friends sail toward the Undying Lands, I too have completed a passage. I feel no elation but heaviness, a nostalgia akin to grief. After the holidays I will be starting a new job, leaving the LHC after 11 years, switching from studying the laws of nature to examining the rules of men. It’s a decision I had made before COVID-19 threw everything into disarray, but the pandemic has helped clarify my choice and injected it with urgency.

The inkiness is fading in the east. My Twitter feed is a sea of jubilation. Humans are such needy creatures: We invent symbols, calendars and rituals, as scaffolding for our wishes, but another cycle around the sun does not erase our sins.

On the sixth day in the new year, white supremacists attack the U.S. Capitol.

I watch videos and live streams on social media. Angry mobs scale walls outside the building. They clash with security. They break in. They roam the halls uninhibited. They carry flags of a government that lost the civil war and banners for a president who lost reelection. They are here to contest the defeat.

After what seems like an eternity, uniformed soldiers arrive in combat gear. Plumes of tear gas rise from the balconies. Flash bombs light up the dome. For a moment it looks like the Capitol is in flames. A war is taking place against a pale edifice like it’s the end of times. The scene bears eerie resemblance to a movie I’ve just seen.

Fifty-five years ago, another leader on another continent, worried about losing power, incited his supporters to turn against their government. “Bombard the headquarters!” declared Mao. People familiar with Chinese history are quick to draw comparisons between the Capitol Hill riot and the Cultural Revolution. The parallels are superficial, but the impulse is natural. We all approach new information through the lens of what we know. We notice similarities and trace patterns. We use the past as a map to navigate the present.

During the Black Lives Matter protests last summer, many on Chinese social media posted photos of toppled Confederate statues with the caption that a “cultural revolution” was taking place in the U.S. My mother forwarded me some of these messages and asked why “Black people are so quick to anger.” What she saw invoked memories of her youth, when historical artifacts were destroyed by political fanaticism. Unaware of the social context, she recognized the imagery and assumed the rest.

Spectacle captivates, but it’s never the whole story. Two sides can be equally engaged in battle and share no moral equivalence. What fascinates me is how easily people identify symbols of authority and take their side. My mother didn’t know what the Confederacy was about, but between monuments of stone and a passionate crowd, the crowd must be the trouble. Order, however unjust, was preferable to chaos.

Politicians and pundits spare no adjectives in denouncing the violence at Capitol Hill, which, in this case, is fair but insufficient. Violence is the spectacle; by itself it says very little about the justness of the cause while concealing underlying structures of power. The rioters are referred to as criminals, insurrectionists, domestic terrorists, which may all be legally correct, but these labels imply the righteousness of state authority and miss the most important point, that the rioters are white supremacists.

In a country founded on stolen land and built with slave labor, white supremacy has always worked with the state, often as the state, and occasionally against the state; only in the last instance does the establishment punish the rogue actors to preserve its power. From slave patrols to modern-day police, violent organs of the state have functioned to uphold structural racism and suppress its challengers. John Brown was tried, convicted, and hanged for treason. The men of the Sioux Uprising were tried, convicted, and hanged for rebellion against the U.S. government. Klansmen lynched with impunity. Martin Luther King jr. was “the most dangerous Negro,” according to the FBI.

Turmoil triggers fear. Bloodshed shocks the conscience. By promising safety and stability, the state justifies its monopoly on violence and expands its arsenal. In the immediate aftermath of the Capitol Hill riot, over a dozen anti-protest bills have been introduced in state legislatures across the country. As reported by The Intercept, “most of the bills have their roots in responses to last summer’s protests against police brutality.” One of them, put forth in Minnesota, seeks to restrict Indigenous-led activism against oil and gas pipelines.

“Some of us did NOT die.” Speaking at a lecture shortly after 9/11, the poet June Jordan posed these questions:

“And what shall we do, we who did not die?

“Is there an honorable non-violent means towards mourning and remembering who and what we loved?

“Is there an honorable means to pursue and capture the perpetrators of that atrocity without ourselves becoming terrorists?

“I don’t know the answer to that.”

That afternoon, when the Capitol was under siege, I was trying to deal with paperwork.

It’s for my new position, a requirement from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to every employer, an otherwise-straightforward process complicated by COVID. After a few days and many emails, I speak on the phone with a specialist from human resources, who patiently explains that my documents have to be verified in person by a licensed representative.

The DHS is very strict about this, she says.

Mandating in-person contact during a pandemic does not sound very secure, I say. I regret my snippy remark. The woman is only doing her job. She is trying to help me. If the DHS were a person, he would be just old enough to vote. The department and its many agencies, ICE included, were only established after 9/11.

If you don’t do this, they can term you, the woman says. What does “term” mean? I ask. Term, terminate, she says.

I will never get used to the casual violence in the English language: Terminate a person. Break a leg. Kill time.

As instructed, I book an appointment at a public notary, put together the files and place them in an envelope, and head out the door. I arrive at the office and am the only customer there. I take out the envelope and lay its contents on the table: my passport, my visa, my social security card, my state ID, my appointment letter, forms and instructions. My immigrant psyche errs on the side of redundancy. I’ve printed out an extra copy of the form, in case a mistake might be made when filling it. Despite my face mask and layers of winter clothing, I feel naked, every inch of my existence exposed.

A young man walks in and says he needs to verify some papers for DACA. Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a policy announced by President Obama that gives temporary protection to undocumented immigrants if they were brought to the country as children, has been put on hold by the Trump administration and is being litigated through the courts. The acronym cuts into me like a blade. I don’t know how to react to this knowledge: Should I look at the young man, smile, nod, signal some kind of empathy or encouragement? Or is it better to avert my eyes under the guise of privacy, even when there is none at this place?

The notary worker points the young man to the other side of the table, where he sits and waits. I want to tell the worker to help him first, that his case should take priority over mine. But I’m afraid of sounding pretentious, so I bite my tongue. Certifying the documents does not take long. All my inner strife is indeed selfish. I’m projecting my own insecurities on a stranger. My vulnerabilities and privileges are laid bare on the slab of wood in front of me. An unjust system has branded me “alien,” but, through its cruel, arbitrary logic, has also deemed me a more desirable type of alien than the young man’s parents. I too am complicit in the injustice.

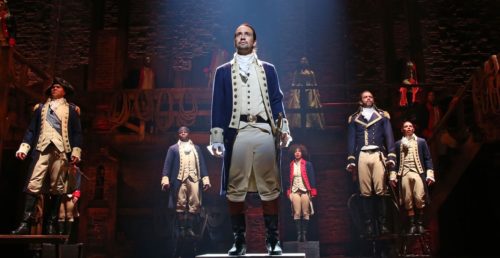

In 2019, the actor Viggo Mortensen, who portrayed Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings, penned an open letter criticizing the Spanish far-right party Vox for using his character to promote its ultra-nationalist ideology. The offending image, a blurry still from the third film, depicts Aragorn charging at the Orc army by the Black Gate of Mordor. Earlier in the scene, the future king gives a rousing speech to rally his troops, ending with these words:

“By all that you hold dear on this good Earth, I bid you stand, Men of the West!”

On Middle Earth, the West is good; evil rises from the East and creeps in from the South. Even when enjoying the films, I’m disturbed by the concept of the Orc. Beauty is political. These condemned creatures, deliberately deformed to evoke horror and disgust, appear to live only to slaughter and be slaughtered. In a 1958 letter, Tolkien described the Orc as “squat, broad, flat-nosed, sallow-skinned, with wide mouths and slant eyes: in fact degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-types.” I recoil at the words, if this is how the celebrated author saw me and my people.

The alleged racism of The Lord of the Rings has long been a subject of academic debate. I’m not a Tolkien scholar and do not really care for his personal views. The imagination of an artist, however expansive, is constrained by individual experiences. The planet of one is always tilted and incomplete. World maps are printed with a different orientation in the U.S. and China: both countries put themselves at the center.

The moral geography of Middle Earth is that of a white, European man. Instead of focusing on the implicit meaning in its directions, a more fundamental question lies in the act of mapping itself. A map does much more than locating a place. It creates the place. It names and defines: land or sea, shared or owned, interior or frontier. Maps establish order. Conflicting drawings become causes for war.

A map divides up territory as well as its inhabitants. People and places become civilized or primitive, trusting or suspect, us or the other. On Middle Earth, evil is embodied by another species so men stay innocent even in battle. Men need the Orc to become men. Borders protect an identity. When migrants and refugees are depicted as criminals or an invading army, their humanity is discounted; their survival is no longer our responsibility. In the logic of war, loss of life on the other side is not to be grieved.

It is the night before the inauguration. D.C. is under lockdown. Talking heads on TV are describing barricades in the streets and troops camping at the Capitol. It reminds them of Baghdad, they say. How marvelous is American exceptionalism that such a comment can be made with no hint of irony. If history offers any lessons, it’s that foreign wars always come home.

Six hundred miles away in Chicago, I observe the cityscape from the perch of my apartment. I’m fixated on the block beneath me. Lights change. Cars and buses go by. The tranquility is almost deceiving. For months I’ve tried to picture the city under martial law, mentally placing armored vehicles on the same stretch of cement and concrete. I’ve packed emergency to-go bags. I joke that quarantine is good practice for internment.

I have no hero fantasy or martyr complex. I want to live, so I do not delude myself to the very real forces in this country that endanger my being. Living is not the same as staying alive, though the latter can be its own accomplishment. I want to be as free and clear-eyed as possible, a perilous condition in a world bent on erecting barriers and sustaining lies.

Something is different about the view tonight. It’s taken me a second to realize that it is snowing. The flakes are tiny and dense. Only by the edge of my window, where the light hits just right, can I make out individual specks in their crystalline structure. The city is drenched in a tender milkiness. Illuminations from nearby buildings soften their glare.

Humans are guilty of reading too much into the weather, burdening the heavens with our earthly woes. I resist the urge to connect the snow to anything in the news. What comes to mind is an old saying in Chinese, ruì xuě zhào fēngnián 瑞雪兆丰年, the auspicious snow signals a new year of harvest. The succinct, five-character phrase conveys an aged, agrarian wisdom: Frozen fields exterminate the pests. Blankets of snow shelter the seeds and melt into nourishment when the new season comes.

It’s been an unusually warm, dry winter. When I left China for the U.S. 11 years ago, Chicago’s notoriously harsh weather was one of its appeals. My mother could not figure out why. She attributed it to youthful rebellion, that I was trying to prove my toughness. There is some truth to that, but I also appreciate well-defined seasons. Icy temperatures at the beginning and end of a year offer reassurance, a rightness of the universe at work.

I know it’s scientifically unsound to extrapolate from anecdotal evidence. This mild, snowless January unsettles me not as a data point but as a reminder that the climate is changing. The surface of our planet is disintegrating as a result of human activities. This pandemic is part of the greater trend.

After rewatching The Lord of the Rings, I tweeted that “(t)he Ents flooding Isengard is the only morally unambiguous moment” in the trilogy. It’s interesting how this episode barely registered when I was little. As children we were taught to obey order, to respect the rules, to distinguish heroes from villains and always side with the near and dear. If only reality were as simple. Nations are imaginary. Borders are artificial. The best and worst of humanity are as much in us as well as the other. How much blood has been spilled, how many lives ruined, to uphold illusory boundaries when the outcome is collective demise?

In the film, Treebeard, a shepherd of the forest, treks to the outskirts of Saruman’s base, where the white wizard has been building an army to take over the kingdom of men. Trees that have stood for centuries are felled for room and fuel. Greenery gives way to fire and steel. In his outrage and grief — “Many of these trees were my friends!” — Treebeard summons his fellow Ents and marches into Isengard. They tear down factories of war. They open up dams and let the water come. Nature takes its revenge.

“Long before any numerals or mathematics, when human language was first naming the world, trees offered their measures — of distance, of height, of diameter, of space,” wrote John Berger. Once upon a time, trees “were taller than anything else alive, their roots went deeper than any creature; they grazed the sky and sounded the underworld.” Modern technology has taken our species to outer space and the bottom of the sea, taller and deeper than the reach of any tree. By seeking domination over the natural world, we’ve lost the coordinates for our moral compass. When progress is assumed to follow a singular direction, when exploration is driven by greed, in our fanatic chase for supremacy, we have moved further away from the essential truth, that all of us are intimately connected with and dependent on each other.

Everything that exists in this world — that has existed and ever will exist — are part of the same story, woven into the same fabric. Carbonized bodies of ancient trees cycle through the earth and linger in the air. The trees shall have the last word.

It is the morning of Inauguration Day. The sky is clear. The city is covered by a light dust of snow. I open my laptop and click on a livestream of the ceremony. I make tea and sip it slowly, letting the warmth thaw what the past four years have frozen. This moment, undeniably victorious, still seems unreal.

Threats from white supremacists have prompted many to suggest canceling the ceremony, moving it indoors, or hosting it over Zoom. None of these were viable options, of course. A presidential inauguration, like state power itself, is as much about pomp and circumstance as it is about legality. Appearance is part of the substance.

Growing up in an authoritarian country, I’m no stranger to political rituals. In elementary school, I was prone to fainting during the flag raising ceremony every Monday morning. The doctors found nothing wrong, and my mother blamed it on the early hour. In retrospect, I think my body shut down in protest. Even at a young age I was skeptical of authority.

A little over a year ago, my mother sent me a video of the grand parade celebrating the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic. You must watch this, she said. The procession of tanks and missiles had moved her to tears. I had watched it the day before, when the event was broadcast live. Instead of joy or patriotic pride, the unabashed display of military strength elicited abject horror.

“It says so much about you, and nothing kind, that you remind people of your birth by showing off your ability to kill,” I wrote in an essay for the occasion, addressed to my homeland. Many in the U.S. read the letter and praised it, that quote in particular. I wonder if they feel the same at the sight of the U.S. military, when their country flexes its muscles.

To most people, the problem is not “bombs” but “whose bomb.” State power is benevolent when it is on their side. Blinded by privilege and a lack of imagination, they cheer the state and bask in its glory, unable to picture its forces turning against them. The ones who suffer because of the state are conveniently ignored or purposefully dehumanized. Citizenship takes meaning by being exclusionary.

“America is back,” the new president declares. I do not question Joe Biden’s personal decency or the good intentions of him and his team. I also know what he wants to convey with this line and how it’s actually read by the majority of people on this planet, who are not white, male, or American, are vastly different. The distance is the purported idea of America and the unforgiving record of history.

When watching The Lord of the Rings, I’ve always found the coronation of Aragron to be anticlimactic. The scene I reflect on is earlier in the film, when Gondor is under assault and Aragorn enters the White Mountains to summon the Dead Men of Dunharrow. The dead soldiers pledge their allegiance because he is heir to the throne. These men had once abandoned their king in battle; only by fulfilling the oath can their spirits be released and be at peace.

I would like to reverse the theme and reinterpret the narrative. The dead are not indebted to the living. They owe no allegiance to any king or creed. In the underworld there are no borders, no citizenship. In the words of James Baldwin, it is us, the living, who are willing to sacrifice all the beauty in this world, who imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, churches, flags, armies, nations, “in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.”

Aragorn travels the Path of the Dead unscathed not because of his royal bloodline, but because he is an exile, an orphan raised on foreign land, a wandering soul reluctant to assume the crown. To be in exile is to experience a little death, to embody a form of nonexistence, to be severed from the past, to abandon an identity, to step to the edge and surrender to the air.

Over two million people have died from COVID-19. One fifth are in the U.S. Like water flooding over an uneven landscape, the pandemic has exposed structural inequalities while making a mockery of conventions of security. But some of us did not die. So what shall we do, we who did not die? What lessons have we learned to deserve this chance at life? What can we tell the dead that will not enrage by its triviality? What do we owe the future, the lives yet to be born?

I don’t know the answer to that. I know to survive we must learn to interrogate the sacred and part with the dear. Many a night thick with grief, I recite this verse by Wislawa Syzmborska:

If there is justice, here it is.

To die as much as necessary, without overstepping the bounds.

To grow again from a salvaged remnant.

We, too, know how to split ourselves

But only into the flesh and a broken whisper.

…The chasm doesn’t split us.

A chasm surrounds us.

Read more of Yangyang Cheng’s Science and China Column on The China Project.