This Week in China’s History: February 11, 1724

“This religion must be rigorously forbidden.”

On February 11, 1724, this sentence was published and circulated throughout China’s provinces in an edict that (sort of) banned Christianity in China. Part of a complex tangle of political, cultural, diplomatic, and, yes, religious forces tugging at the Qing empire, this 1724 proscription is generally seen as ending the Golden Era of Catholicism in China, which had begun with Matteo Ricci’s arrival at the Forbidden City in 1601 and included the conversion of some 250,000 Qing subjects.

The move against Catholicism did not begin with the Yongzheng emperor. The sentence we began with was part of a memorial the emperor composed the previous year by the Manchu Gioro Mamboo (Chinese 觉罗满保 Juéluō Mǎnbǎo), Governor-General of Fujian and Taiwan. That Mamboo was working in Fujian, specifically, matters: it was the part of the empire with the highest concentration of Christians, and their standing in society was greater than just about anywhere else in China. (The Fujian Christian community’s origins has been elaborated by Eugenio Menegon in his award-winning Ancestors, Virgins, and Friars, and its later years by Ryan Dunch in Fuzhou Protestants and the Making of Modern China.)

The prominence of Christians in Fujian — still a tiny minority — drew scrutiny and scorn. Mamboo charged that the Christians were violating Qing law by failing to properly honor ancestors or perform required rituals. For a Manchu stationed far from home and near the cultural heartland of Jiangnan, any threat to the social fabric that had been torn so violently just a few generations before needed to be watched vigilantly.

“The Europeans who are at the court are useful there for working on the calendar and other services, but those who are in the provinces have no use whatsoever,” Mamboo and other Manchus officials advised the emperor in 1723 (presented here by historian Jocelyn Marinescu in her study of the Jesuit response to the 1724 edict). “They attract to their law ignorant people, both men and women. They raise churches in which the people assemble indifferently without any distinction of the sexes on the pretext of praying. The empire receives no advantage at all…The temples that have been built must all be transformed into buildings of public use. This religion must be rigorously forbidden. Those who have been blind enough to follow this religion must be obliged to correct themselves immediately. If they continue to assemble for praying, they must be punished according to the laws.”

Mamboo’s words were part of a vigorous debate that sprung from the Kangxi emperor’s death. Christianity was controversial at court. In the late Ming dynasty, Catholics — mainly Jesuits — had advised emperors on astronomy and other scientific matters, and that had continued under the Qing emperors. The Shunzhi and Kangxi emperors, especially, had close personal relations with Jesuits at court. Among the hundreds of thousands of Qing subjects who became Catholic were a handful of government officials, part of the Jesuit strategy of “top-down” conversion that hoped to eventually achieve mass conversion. But by the end of Kangxi’s reign, the place of Catholicism was becoming contentious as the aging emperor expressed frustration with the increasingly rigid policies coming from Rome.

At the heart of the tension was the so-called Rites Controversy. Jesuits, following Matteo Ricci, accepted Confucian rituals as secular, civic functions, an interpretation that enabled converts to continue venerating their ancestors. This policy fueled Jesuit successes, including roles as imperial advisers and tutors. Other orders, though — Dominicans especially — objected, arguing that “ancestor worship” constituted idolatry. The dispute had as much to do with church politics in Europe as with practices in China, as anti-Jesuit forces gained power and pressured the papacy to forbid the Jesuit interpretation (this pressure would lead to the suppression of the Jesuit order altogether in 1773). By 1721, Rome’s insistence that Chinese Catholics could not perform Confucian rituals led Kangxi to forbid Catholic teachings in the realm, though he later relented.

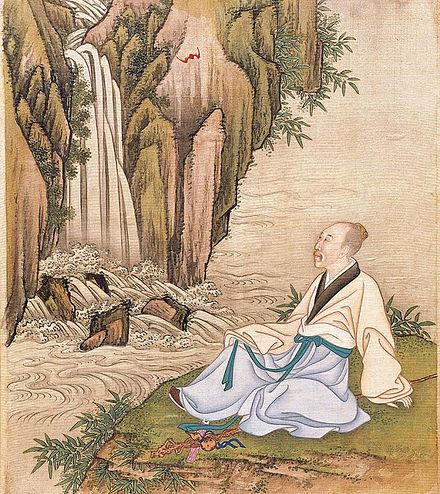

Kangxi died in 1722, and the tensions continued under his son, the Yongzheng emperor. The succession to Kangxi was fractious, and many of the opponents to the eventual Yongzheng emperor were themselves Christians. This, together with the increasing prominence of Christians in many parts of the empire, led to what Eugenio Menego has described as “the Christian conundrum of Yongzheng.” Menego analyzes Yongzheng’s decision to clamp down on Christianity by focusing on three areas: Qing state-building; legitimacy and loyalty to his father’s legacy; and the role of religion in society.

The Jesuit advisors at court had long been important in specialized roles. They had gained the trust of Ming emperors by predicting celestial events like eclipses more accurately than their Chinese counterparts (one legacy of those early encounters is the observatory in Beijing, which includes replicas of the original 17th-century instruments). Yongzheng wanted to retain those services — even the ministers who wanted to limit Christianity allowed that “those Europeans who are of utility may reside at the court.” Nor did Yongzheng want to appear unfilial: though the relationship had frayed near the end, Kangxi’s attitude toward Catholicism, and especially the Jesuits at court, was generally warm. Yongzheng worried that contradicting his father’s policies, especially so soon after taking the throne, could jeopardize his legitimacy.

The place of religion in society, however, gave Yongzheng pause, especially with the hardening of attitudes in Rome, and it was this that Mamboo’s memorial addressed. Yongzheng was worried about religion generally, not just Christianity. Menego points out the lengths that Yongzheng went to impose order on Buddhist and Daoist monks, taking a census and ensuring that they conformed to established regulations. And his concern about “heterodoxy” was even greater. One of the signature edicts of his reign explicitly added Catholicism to the list of “heresies” alongside non-standard Buddhist and Daoist practices.

Yongzheng’s edict — issued January 12 and then published and distributed February 11 — didn’t go as far as Mamboo wanted, and is rightly called a proscription, not a ban. Christianity wasn’t banned in the Qing empire, but it was strictly limited. Yongzheng allowed foreign priests to remain in the capital, where they could continue their work advising the court, but the edict expelled missionaries who were working outside Beijing, requiring them to move to the Portuguese enclave at Macau. Qing subjects were forbidden from practicing Christianity, a prohibition that would last more than a century.

The Jesuits, especially, scrambled to respond. They had built long and rich relationships across the empire during nearly 200 years working in China. Jocelyn Marinescu has documented a broad campaign aimed at reversing Yongzheng’s edict. They did not succeed — though in an ironic twist, China became the last place where Jesuits could find refuge after the order’s suppression: banned from working in Europe, the last handful of Jesuits remained in Beijing, working mainly as court painters. The last one died just a few months before the order was restored in 1814.

Of course, Yongzheng’s edict did not end Catholicism. Henrietta Harrison’s The Missionary’s Curse documents the persistence of the faith, despite the formal ban on Christian practice, among villages in Shanxi for centuries after the “Golden Age” ended. This persistence notwithstanding, the 1720s did mark the end of an era for Catholicism in China, and after Christianity was once again permitted — this time as part of imperialist expansion in the Opium Wars — it was Protestant, not Catholic, missionaries who led the way.

Yongzheng wanted, perhaps, what rulers always want: people who will serve their state but not threaten its order. In other words, keep the Jesuit advisers working in the capital, but stop the practice of religion where it could not be easily controlled. Anyone who has been in China during the Christmas season knows well that attitudes toward Christianity remain complex, and often confounding. I have led more than one group that has insisted that Christianity was suppressed and censored in China, and watched the puzzlement spread over their faces when we walked into the lobby of a hotel with a 100-foot Christmas tree and Santa decorations. Mamboo’s exhortation has never been achieved, but the tensions surrounding the proper attitude toward Christianity persists.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.