This Week in China’s History: February 21, 1875

In recent weeks, the coup in Myanmar has raised many questions, not least of which how China is reacting to what is going on. China, along with Russia, blocked serious action by the UN Security Council, and among the greatest mysteries has been a series of secret, undocumented flights between Yangon and Kunming. For decades, Myanmar has both feared and solicited its much larger neighbor, and the change in leadership raises new opportunities and challenges for the relationship.

But secretive and confusing border crossings in this part of the world are nothing new. This week, we look back to one such case — with international consequences — from the 19th century.

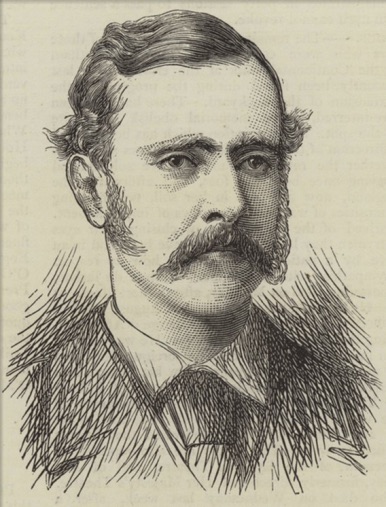

On February 21, 1875, near the Qing border with Burma, as Myanmar was then known, British diplomat and explorer Augustus Margary set out to survey a new railroad line that would, his sponsors hoped, enable easy transportation from the coast to the mountainous interior. In the two decades since the Treaty of Nanjing, British trade on the coast had burgeoned, but reaching inland areas like Yunnan remained a challenge. Margary was separate from the main survey party, led by Colonel Horace Browne, going ahead to scout out possible routes through the mountains.

The next day, Browne’s party of surveyors, protected by Burmese and Sikh troops, was attacked, perhaps by Qing soldiers and local militia, maybe by outlaw bandits. Though Browne’s forces escaped, they learned in the encounter that these same attackers had encountered Margary’s group the day before. Exactly what happened is not clear, but all five (some accounts say six) of the men were killed and decapitated, their heads displayed for all to see.

The event was quickly dubbed the “Yunnan Outrage” and is today all but forgotten. Later known as the “Margary Affair,” it shaped the course of British imperialism as it neared its peak.

China’s southwest — roughly the provinces of Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, and parts of Sichuan — has long been one of the most loosely integrated into the state. During the Qing dynasty, northern border regions from Manchuria and Mongolia to Xinjiang were often the focus of military campaigns aimed at incorporating them into the empire, but the southwest was in many ways more remote. The mountainous tropical jungles of the region and mix of cultures was alien to the ruling Manchus, who struggled to adapt from the continental, often cold, plains of the north.

Nor was this new or unique to the Manchus, who completed their conquest — such as it was — of Yunnan in the 18th century. In Ming times, too, the southwestern frontier was at, or just beyond, the limits of central control.

Imperial power in the region was not uniform or centralized, but diffused via a loose patchwork of alliances, rivalries, and accommodations with local tribes and sovereign states. In his book Asian Borderlands, Wellesley College historian C. Patterson Giersch describes the region of weak hierarchy and porous borders as a “persistent frontier” where, for centuries, Burmese, Siamese, Chinese, and Manchu empires ebbed and flowed, interacting with the local Tai, Kachin, Karen, and other groups.

In the 19th century, the British and French empires strode into this mix. European imperialism after the Opium War focused on the coastal treaty ports like Shanghai, but the promise of the Chinese interior was irresistible. If only the transportation challenges could be overcome, the opportunities seemed limitless. For Britain and France, this lower-left corner of the Qing state was important for other reasons too. Both had a presence on the other side of the border: the British in Burma and India, the French in Indochina.

Eager to link up their commercial empires in Shanghai and India overland, rather than rely on the maritime route, British surveyors set out — after a decade’s delay brought on by a civil war that pitted Chinese Muslims in the region against the Qing state — from Burma to chart a route that would connect their colonies. The British had another goal, too, which was to establish and map out precise boundaries. As Robert Bickers puts it in his essential The Scramble for China, European empire-builders suffered from a “kind of cartographic sickness…ponderous weighing up of ‘our’ or ‘their’ ‘influence’ and ‘interests’ and how to effect, protect or demonstrate these.” This mapmaking was itself an imperialist project, contrasting sharply with the often ambiguous and flexible boundaries that typified the region and enabled the kinds of power structures that functioned there. Europeans wanted to impose their version of empire, they needed clear maps of what they intended to rule. The railroad survey was part of that project.

The surveyors began in Bhamo, in Burma, and headed east. Augustus Margary, a translator and official working in Shanghai, was sent to meet the surveying team in Burma led by Colonel Browne, to provide documents so that they could cross into China. They met as planned in January and began their work, crossing into Yunnan in February.

Margary and his four staff went ahead as the group scouted potential routes for the planned railway. The only thing we know for sure is that on February 21, everyone in Margary’s party was killed, their heads displayed outside the town walls of Mángyǔn 芒允.

Untangling exactly what happened to Margary is difficult. News didn’t reach British diplomats until April, and Margary had been dead for more than a year before British officials arrived in Yunnan to investigate. As David Leffman wrote in an article about Margary’s death in The Diplomat, many people had motives to attack the British, even if Margary himself seems to have been collateral. Leffman points to the locals who, weary after nearly two decades of war, might have feared that the British presented a new invading army (Browne’s expedition was well-armed, though Margary was not), or local Chinese merchants who worried about commercial competition the British promised to bring, or the officials who ran (and taxed) the mule trains that the railway would supplant.

After investigation, the local Chinese magistrate found that “the murderers of Mr. Margary turn out to be wild hill-men, robbers by profession…and certain renegade Chinese who have fled from justice and joined the savages.” According to testimony, a group of bandits set upon Margary and demanded blackmail. Margary refused, shooting one of them before being overwhelmed and hacked to death with swords.

This account is certainly possible, though these “wild hill-men” — Kachin tribesmen — were convenient scapegoats for Qing authorities still trying to impose order on the region just a few years after the end of the devastating Panthay Rebellion. The Qing government, they asserted confidently, certainly had nothing to do with the murder.

British investigators, though, disagreed, and found guilt in the Chinese government, starting with Cén Yùyīng 岑毓英, the governor of Yunnan. Cen’s xenophobia was well-known, and he was more than capable of murder: the blood of some 5,000 Chinese Muslims massacred in 1856 was on his hands. Attacking Margary and Browne was consistent with Cen’s desire to rid the province of foreign invaders.

Another possibility was Lǐ Zhēnguó 李珍国, a Qing military officer who had, a few years previously, taken up arms against the British. Li had worked as a mercenary guerrilla during the Panthay Rebellion, hired by local merchants to protect them against the war. In 1875, Li was no longer a mercenary — he was a Qing military officer — but some suspect that he was hired to protect the merchants again, this time against potential British competition.

According to this version of events, Margary, surveying ahead of the main party along with four Chinese staffers, was joined near Mangyun by two Qing Chinese officials. Acting on the orders of the provincial governor, the two men knocked Margary from his horse and killed him, before finding his assistants in the monastery where they were staying — and killed them as well.

Although the Qing denied any responsibility, the British insisted on it. And, as in other events like the Arrow Incident of 1856, Britain used their grievance to press for more concessions. Eighteen months after Margary’s death, China signed the Chefoo Convention, accepting responsibility for the murder, requiring local officials to protect British passport holders, and opening five more treaty ports to trade. Several bits of trivia accompanied the Chefoo Convention: it was signed by Lǐ Hóngzhāng 李鸿章 for the Qing, and Thomas Wade (of Wade-Giles fame, eventually the first professor of Chinese at Cambridge) for Britain. The treaty also called for a formal mission of apology, which brought Guō Sōngdào 郭嵩焘 to London in 1877. Guo’s mission took up residence at 49 Portland Place in London, which became not only China’s first overseas diplomatic mission, but remains the address of the Chinese Embassy to Britain.

In the coming weeks, we may see whether there will be lasting international ramifications to what is going on in Myanmar, and how significant China’s role in it might be. But it is worth remembering that the region has a long history with international conflicts that belie its reputation as remote.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.