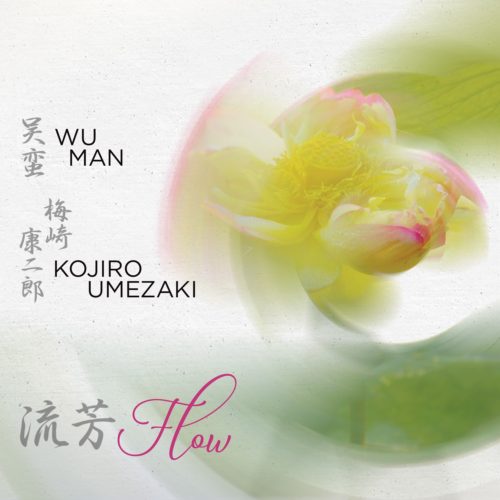

In ‘Flow,’ the pipa and shakuhachi speak to our souls

Wu Man and Kojiro Umezaki have created a five-track album that is at once contemplative and dynamic, a contemporary and stylish fusion of classical East Asian music.

A long time ago, in an era before Zoom meetings and video chat dates and elbow-bump greetings, human time was measured by the seasons. Unlike human time today, seasons came and went; temperatures rose and fell without thermostats to regulate them; humans altered their daily routines to accommodate a strange collective phenomenon known as “weather.”

This is a purely imaginative exercise these days — a quaint idea, isn’t it, that each day is different from the last one — but it’s a form of imagination in which Wú Mán 吴蛮 and Kojiro Umezaki, in Flow (流芳 Liú Fāng), demonstrate a particular expertise. The 33-minute album, released on February 19, features five songs performed with traditional East Asian instruments, most prominently the pipa, the pear-shaped Chinese lute, and the shakuhachi, a Japanese end-blown flute commonly constructed from bamboo. Four songs are inspired by each of the four seasons, while the fifth, “Bamboo,” both conjoins and survives them.

I listened to these songs alone. And if you’ll indulge me a personal disclosure, I listened to them after a particularly awkward COVID-era in-person date in which I discovered, not entirely to my surprise, that my social skills had atrophied during the pandemic winter. I slinked into my kitchen and stood there, staring at the humming refrigerator, as my heart launched a rebellion against my ribcage. I needed to talk to someone. And, by listening to Wu Man and Kojiro Umezaki’s album, that’s more or less what I did.

Originally commissioned to accompany a 2019 video installation of a classical-style garden at the Huntington Library outside Los Angeles, Flow now stands alone as a monument to the garden and its seasons. It is also a testament to our shared natural environment, and as such, a gentle reminder of what all of us have in common, even now. When I spoke with Wu Man and Kojiro Umezaki about the album, both emphasized the communication between them — specifically Wu’s expressive pipa and Umezaki’s soulful shakuhachi — as they composed the album improvisationally. In theme and in origin, then, the album is a balm for the endless Now of pandemic estrangement.

The album’s first track, “Winter (Night Thoughts II),” establishes Flow‘s diverse tone, featuring the plucked musings of a lonely pipa alongside long silences punctured occasionally by chords. The song’s Chinese title is shared with a Lǐ Bái 李白 poem, “Quiet Night Thought” (静夜思 jìng yè sī): “Before my bed there’s a pool of light / I wonder if it’s frost on the ground / Looking up, I find the moon bright / Then bowing my head, I drown in homesickness.” The track builds frenetically, like a mind folding recursively on itself. But it doesn’t end there — the lonely searching notes return to close out the piece.

“Winter is peaceful sometimes, but sometimes it gets emotional, it gets intense,” Wu Man explained. Wu’s skill is to both manifest this emotionality and refract it, like moonlight on floorboards.

The album’s second and third tracks, appropriately titled “Spring” and “Summer,” feature shakers and the breathy shakuhachi, suffusing the tracks with an ephemeral vitality that, after Winter, feels both expansive and liberating. Umezaki explains that the shakuhachi, unlike many instruments associated with the West, solicits meaning within the notes rather than between them; it pares virtuosity for intensity, encouraging listeners to dwell in the sound. When played alone in “Spring,“ the shakuhachi carries the melancholia of a cold wind, which is comforting in its own way — a reminder that the winter was real.

I asked both Wu and Umezaki why the album so successfully conjures the seasons even to a listener, like myself, who is only passingly acquainted with the pipa and shakuhachi traditions. Each cited the lineage of the instrument. Pipa taps into something old, Wu told me, an accumulated knowledge: “Through all the thousands of years, it has developed a distinctive language.” Umezaki pointed to the shakuhachi’s storied employment as a Buddhist breathing device. The album may articulate the seasons clearly because its instruments, in the hands of two honest guides, have experienced many of them.

The year has four seasons but the album has five tracks. The fifth one is “Bamboo.” Umezaki explained its presence pragmatically — “The original video installation [which the music was composed to accompany] was actually five different pieces, the seasons plus ‘Bamboo’” — but gamely added that in a garden, bamboo “creates the space” for the garden.

Wu Man offered a contemplative suggestion. “Bamboo is evergreen. It’s always there. It doesn’t matter whether it’s winter or summer, bamboo is always green, always alive,” she told me. “We wanted the listener to take something away, something they can imagine.”

From my bedroom in Palo Alto, I imagined motion again, seeking human companionship again, returning to my normal awkward, not this tragicomic COVID-awkward. I saw clouds racing across a meadow, shadows on the grass. Swaying bamboo. Four seasons later we are still here, listening to music by ourselves, battered but unbroken.