The last of New York’s ‘Chinese hand laundries’

Last summer, one of New York's last "Chinese hand laundries," operated by Robert S. Lee, closed. "Chinese hand laundry" refers to laundry businesses from a specific period, when Chinese immigrants from Taishan, Guangdong were closely associated with this line of work.

A Chinese version of this story, also by Eveline Chao, was published in the Chinese edition of the New York Times on January 6, 2021.

On the last Saturday in August, a small crowd gathered outside Sun’s Laundry at 626 East 14th Street in Manhattan. Neighbors, family members, and a small pool of reporters had come to say goodbye to one of the last “Chinese hand laundries” in New York City. Owner Robert S. Lee (李洪森 Lǐ Hóngsēn), 84, was shuttering the family business he had founded with his parents and run since 1959. It was the last of five laundries that various members of Mr. Lee’s extended family had run.

“For decades, Chinese immigrants have always experienced a ‘bamboo ceiling’ in American society,” Lee said. “We Chinese have always endured the difficulties and made the best of every situation without complaints.”

But the COVID-19 pandemic proved too much. The closing represented the end of an era for a business that had survived through six decades of thick and thin.

There are still plenty of Chinese-owned laundries in New York. In fact, there was one just down the street — though Lee boasted that his prices were much cheaper than theirs. But his was one of the last from a distinct period in history, from the late 1800s to about the 1970s or ’80s, when Chinese immigrants, most of them from Taishan County in southern China’s Guangdong province, were so strongly associated in the American consciousness with laundry work that the businesses were advertised as “Chinese hand laundries.” During the 1930s, there were 5,000 Chinese-run laundries in the New York metropolitan area alone.

Throughout much of that period, a combination of exclusionary immigration laws and prejudice made it hard for such immigrants, or their American-born children, to find work outside the laundry or restaurant industries. Things began to change during WWII, when the U.S. aligned with China against Japan, and further improved during the Civil Rights Movement, when the passing of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act opened up immigration from Asia.

Lee had closed his laundry in mid-March when the state first imposed measures to stop the spread of COVID-19. He reopened it later in the summer, but with so many people working from home, and many still afraid to leave home, there was very little business. “Today people don’t wear suits or dress shirts anymore,” Lee said.

“A few longtime customers who are loyal to my uncle came to pick up laundry that had been there since March, but that’s it,” added Robert Gee (朱超伟 Zhū Chāowěi), Lee’s 57-year-old nephew who translated his uncle’s Taishanese to English.

Some of the neighbors, now middle-aged, have known Lee since they were children. For them, the laundry was the last vestige of the post-WWII New York of their childhoods. Many said they used to have their packages delivered there, or leave house keys with Lee when guests came to stay. Some brought goodbye gifts, and some picked up final bundles of laundry, wrapped in brown paper and tied neatly with string — the same way Lee’s father had packaged them in the 1930s. One neighbor drew a chalk mural on the sidewalk outside that read, “We will miss you.”

Throughout the last year, the city — and the country at large — experienced a spike in hate crimes against Chinese and other Asians who were blamed for the pandemic. It was suggestive of the 1950s, when Lee first arrived in the U.S., another difficult time to be Asian in America. Back then, there were no relations between the U.S. and mainland China, and tensions grew into outright conflict during the Korean War, from 1950 to 1953.

Even after the war, anti-communist hysteria — the “Red Scare” — raged in the U.S. People of Chinese descent were often suspected as potential spies. Chinatowns across the U.S. were monitored by the FBI, and people who looked Chinese would be randomly stopped and asked to show their citizenship paperwork. The NYC-based Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance, a labor union that Lee’s father, Lee Dow Sun (李道新 Lǐ Dàoxīn), was a member of, was investigated as a suspected communist organization.

Robert Lee is reluctant to talk about any racism or discrimination he may have experienced in those years. According to his nephew Gee: “He did get called names, and sometimes things happened when he was walking to the train, but he says he didn’t pay any attention to that. Whenever we ask him about it, he says, ‘I just did my job, made my money, and went home. It was a long day, and that was it.’”

Lee grew up in Taishan, Guangdong — specifically, from “the Lee Village called Horse Tail Lake — Ma Mei Wu.” His grandfather came to the U.S. first in 1908, followed by several uncles throughout the 1920s and 30s. His father, Lee Dow Sun, came in the late 1930s and established a laundry business in Boston. Barred by U.S. immigration laws of the time from bringing over wives and setting down roots, such migrants sent money back to family in China, expecting they would eventually return there to retire. They also went back to China to have children, and when their sons were old enough, often sent for them to join them in the U.S., following the pattern of generations of Taishanese men.

After Japan invaded the Taishan area, an eight-year-old Lee was sent in 1945 to live with relatives in Hong Kong. His mother, Lee Suet Fong (李雪芳 Lǐ Xuěfāng), managed to join him there in 1949, after experiencing forced labor under the Japanese. Gee’s maternal side of the family has a similar history. Gee’s father came to the U.S. in 1937, at age 15, and went on to become one of the first Chinese electrical engineers for AT&T. “They all intended to go back to China, but then the war came about, and then the communists took over,” Gee said. Nearly seven decades later, Lee has never gone back home for a visit.

In 1956, Lee Suet Fong joined her husband in Boston, and Lee joined his parents one year later. There, Lee took English classes and worked at a commercial washing business. In 1959, Lee Dow Sun and his son purchased the New York City laundry from another Chinese immigrant for $4,300. The rent on their 99-year lease started at $100 per month. The family lived nearby in an apartment that cost $50 per month. “That apartment is now worth more than $2,000 a month,” Lee marveled.

Eventually, Lee returned to Hong Kong to marry Wai Hing Lee (李薇涵 Lǐ Wēihán, who is now 76). She eventually joined him in the U.S. and worked in the laundry, too. “We all worked very hard, with few days off,” Lee said. “I felt it was my duty as the family’s only son to help my parents succeed in every possible way.”

Through the years, the couple saved up enough money to purchase a home in Elmhurst, Queens. He and his wife commuted from there to the laundry — an hour each way by subway. They had two children — son Edward, who worked in the banking industry but is now taking care of his parents full time, and daughter Jane, who is a social worker. They both attended public college in New York.

The area was once considered a derelict neighborhood. One longtime neighbor who gave her name as Lois said that during the crack epidemic of the 1980s, it was common for addicts who had overdosed to be found dead in their homes. Lee’s son Edward said that when people fell on hard times, his father always knew, because they would stop picking up their laundry. Even though the laundry had a 30-day pickup policy, he would set aside items for people he knew. On their closing day in August, one white-haired man introduced himself to family members as “the person who picked up 100 shirts” earlier that year. After he left, Edward said that the shirts had been there since 2015, but that they had set them aside.

Now, like the rest of New York, the area is gentrifying and real estate prices are rising. Lee’s customer base had begun to shift from families to young, single, white-collar workers. But the neighborhood remained supportive to Sun’s Laundry. About five years ago, a new landlord tried to drastically increase Lee’s $800 per month rent, which had fallen well below the market rate. Members of the building’s condo association organized an online fundraiser. Lee refused the money, but the neighbors were able to successfully pressure the landlord not to increase the rent.

Even before the pandemic, business had been on the decline, due in part to changes in fashion and the advent of wrinkle-free apparel. The laundry’s glory days were the 1960s, when suits were standard workwear, through the 1980s, when the finance industry boomed in New York and clients who worked on Wall Street went through many dress shirts each week. Lee said that during those years, he cleaned more than 100 business shirts a day, and had to get other family members to him on weekends. By the 2000s, when more casual dress came into vogue, that figure had shrunk to less than 40 shirts a day.

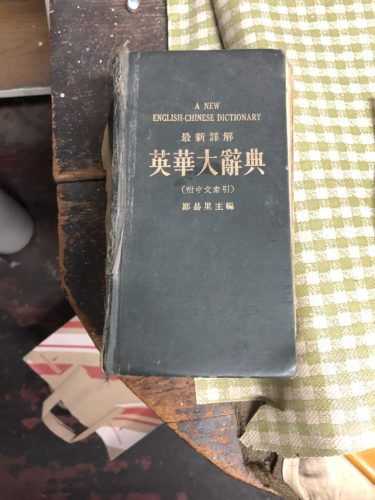

That final Saturday, in between greeting neighbors and conducting media interviews, Lee and his daughter and son cleaned out the laundry. Many old items they gave away to visitors as souvenirs, such as a wooden Taishanese work bench and a Chinese-English dictionary published in 1950. “All the laundries used to have that dictionary,” said a Chinese-American photographer in his 70s named Corky Lee, one of the visitors that day.

Another visitor was Amy Chin, an amateur historian of Chinese American life, who also grew up in a Chinese laundry family in New York. She brought a copy of her father’s 1967 Chinese laundry and business directory to show Lee. They found Lee’s father listed in the directory.

Rob Gee had already claimed a hand-painted sign that used to hang outside the store when it first opened in 1959. He said that he felt grateful to the older generations of laundry workers for doing such difficult work. “It helped a lot of Chinese families survive and put their kids through school,” said Gee, who is a management consultant and former marketing executive for Pepsi-Cola. He was proud that he and his five siblings all have graduate degrees.

“In the 1950s and ’60s, customers used to call them Charlie because they didn’t know their Chinese names,” Gee said. The name refers to Charlie Chan, a Chinese detective in novels written by American author Earl Derr Biggers. The character was often depicted in movies from the 1930s onwards by white actors speaking with a fake Chinese accent.

Today, memories of the days when Chinese people were referred to as Charlie are dying out. So is the longtime association between Chinese immigrants and laundry work.

Since retiring, Lee has been restless. After all, he’s spent more than six decades working. Gee said he had promised his uncle that at some point after the pandemic is over and they’re able to travel again, he will accompany him back to China. There, Lee can finally see the family home in Taishan that the laundry business helped build, where old family photos still hang on the walls. “Imagine that,” Gee said, “a house with photos of us on the wall, and nobody living there.”

“He’s only been on a plane three times,” Gee said — his first arrival from Hong Kong in 1957, and a return trip to get married during the 1960s. “The next wasn’t until 2008, when he flew to Miami for a vacation. After he got back, he kept talking about how he couldn’t believe it only took three hours.”

The last time he saw Taishan, Lee was eight years old. He remembers rural farmland, and his grade school uniform of yellow shorts and red handkerchiefs. He’s eager to see how it has changed. “Retirement will be a chance to relax and enjoy the golden years after 61 years of hard labor,” Lee said.