This Week in China’s History: April 4, 1975

From 1966 to 1976, the Cultural Revolution shaped China and Chinese politics in ways that still echo. The scale of the event was overwhelming — a decade long, schools shut down, millions of people packing Tiananmen Square, a generation of young people relocated — yet some of its cartoonish aspects can make the Cultural Revolution seem less catastrophic than it was. Absurd spectacles like performing the “loyalty dance,” petitioning to have traffic lights changed so that “red” would mean go, etc., obscure millions of tragedies. This week, we look at one such tragedy: a young woman who was executed on April 4, 1975, a bullet to the head ending six years of imprisonment and torture.

Warning: This column contains graphic descriptions.

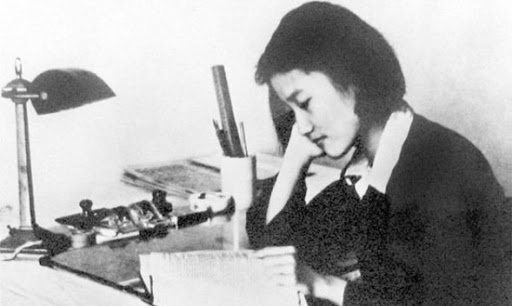

Zhāng Zhìxīn 张志新 was born in Tianjin in 1930, growing up in the Nanking Decade when China was supposedly unified, after the end of the “warlord era.” But the situation remained tense, especially in the north, thanks largely to the steady Japanese encroachment. Her family was well off, with enough leisure and wealth to spend time on music: Zhixin and her sisters even formed a band, one that performed in 1947 for a gathering that included Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石 Jiǎng Jièshí), the Nationalist president of the Republic, as his government was embarking on a war with its Communist adversaries for control of China’s future.

Zhang’s sympathies did not lie with the KMT, though, and when the civil war ended she was proud to become a citizen of the People’s Republic. Like many, her ardor for her new nation surged because of the Korean War, when she joined the People’s Volunteers Army to fight against UN forces. Selected to study Russian, first in a military school and then at Renmin University, she married, joined the Party, and took up a position in the propaganda department in Shenyang.

Joining the Communist Party in 1955 was buying high. The successes of the early People’s Republic exceeded any reasonable expectation, but numerous factors combined to undermine political unity and economic recovery of those first years. The Anti-Rightist Campaign began silencing dissent, and the Great Leap Forward plunged the entire country into calamity.

Zhang Zhixin survived these campaigns, but her misgivings began in 1959, when Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 refused to accept responsibility for or even acknowledge the disastrous effects of the Great Leap. According to Yang Jisheng’s new book The World Turned Upside Down, Zhang saw Mao’s actions at that time as a leftist deviation from the ideological foundations of the Party, which placed the entire country at risk.

Zhang’s misgivings surfaced in the Cultural Revolution. In 1968, she was sent to one of the re-education camps called “May 7 Cadre Schools,” aimed at reforming her understanding to bring it more in line with Maoist thought. Her criticism of Mao was unbowed, though, and she was informed on, denounced, and publicly criticized starting in 1968. In September of 1969, she was arrested.

It’s often observed that the height of the Cultural Revolution was in 1966 and 1967, when the Red Guard movement ransacked homes and persecuted citizens for espousing “old ideas, old culture, old habits, and old customs,” but Zhang Zhixin’s case is a reminder that the violence persisted long after that. Refusing to retract or change her views, Zhang supported purged Party officials like Liú Shǎoqí 刘少奇 and Péng Déhuái 彭德怀, and criticized Mao and his inner circle. It could not have been surprising when she was arrested or even — given that Mao’s nephew controlled Liaoning province — that she was sentenced to death for her views.

The sentence was commuted to life in prison, but this was barely a reprieve, as described by Sheila Melvin for ChinaFile. She was frequently confined in isolation, her cell not big enough to stand. Other sources say that she was frequently manacled, and raped not only by prison guards, but by other prisoners as well, who were rewarded with reduced sentences or special treatment for raping Zhang. Desperate to resist, she spread her own excrement on her body in an effort to ward off rapists. During this time, she recorded her experiences on toilet paper and in letters written to her children and husband (the state imposed a divorce as part of her sentence, though this was later invalidated).

This continued for five more years.

Tormented and tortured, Zhang took to shouting her opposition to Mao, saying that he was the source of all evil and that he should be “hacked to pieces.” This only worsened her treatment.

Adding to the circumstances was a new political campaign, the “One Strike, Three Antis.” The “three antis” targeted corruption and extravagance, but the One Strike took aim at counterrevolutionary thoughts and actions. Zhang Zhixin came clearly into the crosshairs.

Party leaders disagreed over Zhang’s fate. Some wanted her killed to end the spectacle or simply to rid themselves of the trouble. Others demurred, either on the grounds that she was clearly not sane and able to be held responsible, or that she might be used as a negative example. It was this last view that ultimately led to her demise.

Put onstage at a rally in November 1973, Zhang ignored her instructions to criticize Lín Biāo 林彪 and instead shouted criticisms of Mao and his wife, Jiāng Qīng 江青. Two more years of prison followed, before she was tried and sentenced to death, again. This time the punishment was carried out. Following common practice, authorities slit her larynx before she was presented for execution so that she could not cry out any more.

Abused by the Party in life, her memory was also politicized. With Mao’s death and the end of the Cultural Revolution, Zhang Zhixin’s loyalty to the Party but criticism of the radicals who had directed the Cultural Revolution — including the Gang of Four — became useful to those who wanted to turn away from the Maoist legacy. When Zhang’’s family petitioned for her rehabilitation, the request was not only granted, but she was declared a “revolutionary martyr” for her loyalty to the Party against deviants like the Gang of Four. Her story was published nationwide in the People’s Daily at the direction of Hú Yàobāng 胡耀邦, whose death would later catalyze the 1989 protests in Beijing.

The Communist Party has yet to reckon fully with the Cultural Revolution, though its legacy has fundamentally shaped the decades that followed it. The gruesome fate of Zhang Zhixin illustrates the tragedy that befell many who dedicated their lives to the Party only to have it repay them with suffering as it tried to manage its own internal struggles.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.