The yin and yang worlds of a Chinese literary outlier

Wang Xiaobo's translator writes about the enduring cult status of this important Chinese writer, who still remains obscure outside his home country. In some ways, Wang is more necessary now than ever.

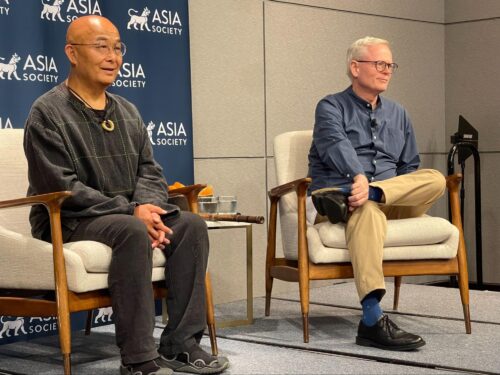

Considered one of the most important literary and intellectual figures of 20th-century China, Wáng Xiǎobō 王小波 (1952-1997) has remained a cultural idol and a cult writer in China since his unexpected death in 1997. Yet there are still few people outside the country who know about this intellectually provocative and stylistically innovative writer. Only one collection of his novellas and a couple of his essays have been translated into English. This Sunday, April 11, marks the 24th anniversary of his death. Hongling Zhang, one of the English translators of his novellas, has written the following to pay tribute to Wang’s legacy.

In China’s contemporary literary scene, Wang Xiaobo was difficult to categorize and interpret. Hailed as an ace outside of the literary circles by his admirers, Wang never joined the Chinese Writers’ Association, the state-run literary organization that offers professional writers salaries, prestige, and political guidance. His life was short — he was born in 1952 in Beijing, he died in the same city in 1997 — and his active literary career only lasted six years. From the time he won the 13th United Daily Novella Award from the Taiwanese newspaper United Daily News in 1991 to his unexpected death from a heart attack in 1997, he streaked across the sky like a comet, yet his real brightness would only shine after he departed the world. In his lifetime, he had only two books published in mainland China, and neither sold well. After his death, his fiction was published in three volumes — The Golden Age, The Silver Age, and The Bronze Age — and his essays in two collections, My Spiritual Home and The Silent Majority. These works were reprinted in large numbers each year. A group of his fans, who styled themselves as “the Running Dogs of Wang Xiaobo,” imitated his writing style and published many books. His writings have become undisputed classics, and he has turned into a cultural icon. Unfortunately, English translations of his writings are still limited, and his name remains unknown to readers outside China. Up to the present, I only know of one collection of his novellas in English, Wang in Love and Bondage, which I translated with Jason Sommer, published by SUNY Press in 2007.

Various labels have been attached to Wang Xiaobo — grassroots liberal intellectual, anti-authoritarian provocateur, Romantic knight, a cultural hero outside the system — and his writings also carry an array of generic descriptors — absurdist, black humor, dystopian fiction, eroticism, surrealism, etc. Indeed, it’s difficult to fit him into any literary school or group in China, and every label attached to him could be a topic for a research paper or even a book. In my humble effort to introduce this beloved writer of mine to English readers, I will borrow the yin-yang concept from traditional Chinese culture to talk about him. This approach might seem to contradict people’s general impression of him, since Wang was an advocate of Western literature and intellectual thought, and wrote extensively to expose the follies of both traditional and contemporary Chinese culture. But he did have a unique understanding of yin-yang theory and had played with the idea in both his fiction and essays. One of his well-known stories is titled “My Yin and Yang World.” And in probably his most influential essay, “The Silent Majority,” he calls the circle which holds the power of discourse the world of yang, and the silent majority, of which he was a part, the world of yin. Contrary to the traditional concept of yin and yang, which assigns positive attributes to yang and negative attributes to yin, in the context of Wang’s writings, the world of yin is occupied by people who don’t want to participate in the maddening discourse of political propaganda and lies and would rather remain silent to preserve their humanity. The world of yang is oppressive and grandiloquent, full of people who are prejudiced, hypocritical, and selfish, who rail at each other publicly. However, the opposition between yin and yang in Wang’s writings is not absolute; the two forces are constantly in a dynamic process of interaction and transformation. Wang Xiaobo’s is the kind of high critical intelligence that demonstrates what F. Scott Fitzgerald famously described in his essay “The Crack-Up” as “the ability to hold two opposed ideas in his mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

The untrustworthy and unethical nature of speech Wang Xiaobo observed in childhood disgusted him into “silence” for many years. This period of intellectual silence (not the literal kind) represents his yin period, lasting 39 years. In his essay “The Silent Majority,” Wang remarks on the novel The Tin Drum, where Günter Grass writes about a boy named Oscar who decides to never grow up after discovering the absurdity of the world around him. Wang points out that although it’s impossible to remain a child forever, it is possible to remain silent for as long as one chooses. He says that after being subjected to the grandiloquence of revolutionary speech during his childhood, he began to have doubts about words. For instance, during the Great Leap Forward in the late ’50s, people collected scrap iron and melted it down in open earthen hearths in their backyards. The adults pointed at the “cherry-red flakes of metal” that had come out of the furnaces and said they were “steel,” which to six-year-old Wang just looked like “cow manure.” The discrepancy between words and truth turned the young Wang into a skeptic. The more vehement and fervent the voices around him, the more doubtful he became.

Wang’s early years were spent in the countryside of Yunnan province undergoing reeducation, and then as a worker in the factories of Beijing making educational equipment and semiconductors. He continued in literary silence as a college student at Renmin University of China, later as a graduate student of East Asian Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, and finally as a teacher in Peking University and Renmin University. In his essay “The Silent Majority,” he writes that there were many people like him in China: “On public occasions we won’t say a word, but we can hardly stop talking in private. Put another way, we will say anything to people we can trust, and nothing to those we can’t.” He calls people like him “the silent majority” or “the disadvantaged group.” The second term comes from sociological research on homosexuals that he and his wife, sociologist Lǐ Yínhé 李银河, carried out for a few years before the essay was written. In the sociological domain, “disadvantaged groups” or “vulnerable groups” refer both to people with economical disadvantages and disabling conditions — such as the elderly, children, and the disabled — and to those who live in the marginalized areas and lack some types of legal identities: migrant workers without city residential permits, the homeless and unemployed without work units, adults without marriage licenses (including sex workers, singles, homosexuals, and transgender people). After doing some research, he suddenly realized that “the so-called disadvantaged groups were simply groups whose speech went unsaid,” after which came another epiphany, that he “belonged to the greatest disadvantaged group in history, the silent majority. These people keep silent for any number of reasons, some because they lack the ability or the opportunity to speak, others because they are hiding something, and still others because they feel, for whatever reason, a certain distaste for the world of speech.” He understood that he was one of those from the last group. By including people like him, who voluntarily choose to remain silent, Wang broadens the connotation and denotation of “disadvantaged group.” Disadvantaged groups don’t simply make up the majority of the population but also preserve humanity. He says his humanity survived the Cultural Revolution because of what he learned from silence.

“On public occasions we won’t say a word, but we can hardly stop talking in private. Put another way, we will say anything to people we can trust, and nothing to those we can’t.”

Eventually, Wang broke his silence and edged into the circle of speech. He left the world of yin and entered the world of yang. This was partially because the circle of speech had begun to disintegrate in the early ’90s and partially because he had reached his middle age. He believed that as a middle-aged man, he had responsibilities to society and young people, and shouldn’t continue to allow the madhouse of speech to talk nonsense. In the last part of “The Silent Majority,” he says, “Blame literature for giving me a foothold within this society; a foothold from which I can attack society itself and attack the entire world of the yang.”

I don’t know if Wang Xiaobo had his essays in mind when he spoke of “literature.” For a long time, and even to this day, many readers still think his essays are better written than his fiction, a comment he took as an insult. In his essay “The Art of Fiction,” he says essays are no more than talking sense — you see the sense there, and you go ahead and talk about it. Fiction, on the other hand, requires a deep understanding of the beauty of invention and a talent to make something out of nothing; he would rather focus on fiction and do it well. But as a human being, he recognizes a need to take moral responsibility and talk sense at certain times, when he can’t hold himself back.

The concept of yin and yang can be applied to Wang’s writing as well. Generally speaking, consciousness might be considered yang, and subconsciousness considered yin; logic is yang, and art is yin; reason is yang, and irrationality is yin. Talking sense and distinguishing right from wrong are conducted at the conscious and logical level; thus, in the realm of yang. Wang Xiaobo’s fiction presents a world that is much darker and more complex, filled with details and images from the subconscious that recreate the strangely familiar and absurdly irrational “reality” of an authoritarian world, whether past, present, or future. As his editor Lǐ Jìng 李静 once wrote, Wang used essays to express his “beliefs” and fiction to sustain his “doubts,” an observation that brilliantly summarizes the major difference between his essays and fiction. In his essays, we see a witty and humorous Wang Xiaobo who has full confidence in humanity’s reason and knowledge; but in his fiction, pessimistic and gloomy clouds are always lingering, the shadow of death looms large, and many scenes remind people of the surreal world in Salvador Dali’s paintings.

Perhaps the best example to illustrate Wang’s unique, subversive understanding of the yin-yang concept is his novella My Yin and Yang World. The narrator of the story is named Wang Er (literally, Wang No. 2), a casual, symbolic name used for most of Wang’s protagonists in fiction. A technician at a Beijing hospital in the late ’80s, Wang Er’s wife divorces him because of his yangwei, or “the shrinking of yang” — i.e., impotence. To avoid ridicule and embarrassment, he moves to the basement of the hospital and lives the life of an outcast, amid junk from different clinical departments and samples of deceased body parts. Quiet and eccentric in his colleagues’ eyes, Wang Er is not all that unhappy about his solitary, underground life. For one thing, he is free of the obligations to attend endless political meetings and study sessions; for another, he is left alone and can indulge himself in activities that seem useless in others’ eyes, such as writing stories that lead him nowhere but into trouble, translating Story of O over and again, a novel that would never get published in China. He calls the time he lives in the basement the “soft period” of his life. During the hard period of his life he lives in the light, and during the soft period he lives in the shadow — these are his yin and yang worlds. He finds that human history can also be divided into yin and yang periods. He quotes what Arnold J. Toynbee says in A Study of History, which Wang Er uses as a textbook for learning English: “Mr. Toynbee says: human history is divided into two states of yin and yang. During the yin state, mankind scatters around the world and lives a primitive, unexamined life of sleeping after eating and eating after sleeping. Later mankind gathers along some river valleys and plains and lives a gregarious life, from which civilizations arise and thus come all the troubles. Like that, my life also has had two states of hard and soft, closely resembling the two worlds of yin and yang.”

It happens that there is a similar character in the story: a much older man, Mr. Li, who also lives in the world of yin. Originally a Russian translator, he later quits his job and devotes all his energy to the study of the Tangut language from the Western Xia dynasty, an endangered language that the country has no use for and people have no need to understand. Unwanted and unemployed, Mr. Li also suffers from public humiliation and his neighbors’ intrusion into his privacy, just as Wang Er suffers the intrusion of his work unit and colleagues. Because of that, Mr. Li regards Wang Er as one of his kind, saying, “From the beginning of the creation, there were two kinds of people in the world: one is our kind, and the other is not our kind. Nowadays there are still two kinds of people in the world. In the future there will continue to have these two.” “We” are the ones who live for what “we” want, and “they” are the ones who live for what “they” should want. In a word, “they” want to live a life that is pre-defined and pre-designed by others.

The idea of yin-yang here reminds me of the yin-yang hairstyle popular during the Cultural Revolution, forced on “Five Blacks” and “Cow demons and snake spirits,” the perceived class enemies of the revolution and the Party. To shame these enemies in public, young Red Guards would shave half their heads and leave the other half unshaven, giving this style of haircut its name: yin-yang. Sun is yang and moon is yin; hot is yang and cold is yin; white is yang and black is yin. My Yin and Yang World also reminds me of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. The narrator, an unnamed young Black man, has experienced erasure and invisibility numerous times in his life and lives in an underground manhole. Like Wang Er, Ellison’s invisible man is abandoned by the society of yang and lives in the world of yin. And like Wang Er, he finds freedom and comfort in his underground life and enjoys his lack of social interactions. Both protagonists write stories and want to live their lives free of control, oppression, and humiliation. While the invisible man loves light and writes about his own life, Wang Er enjoys night and darkness, and we don’t know what he writes about. Wang Er is certainly not an angst-laden character in search of his identity; his self-sufficiency and philosophical sense of life gives him almost a Daoist approach, although not in a traditional sense.

Perhaps people in China are seeking in Wang Xiaobo something they lack.

There is a mirror-image quality about Wang Xiaobo’s fiction, in which yin and yang need to be perceived as reversed. For instance, the traditional theory of yin-yang claims that men are yang and women are yin, but in “My Yin and Yang World,” both Wang Er and Mr. Li are passive males depicted as the embodiment of the yin energy, and Xiao Sun, the young woman gynecologist, is dynamic and self-assured, full of the positive energy of yang. Toynbee refers to human life at its pre-civilized, uncultivated stage as the yin-state, but both Wang Er and Mr. Li want to live a cultivated life in pursuit for knowledge and creativity. People usually think the yang world is full of sunshine and happiness, as opposed to the dark, suffering life in the yin world. But in the story, the yang world aboveground is a space where everything is controlled by authority and individuals hardly have any freedom. The life in the underworld of yin is free and calm. There, Wang Er can fart freely, translate forbidden books, and write stories at will. In the context of Wang Xiaobo’s fictional works, the world of yin is a freer, more desirable place to live than the one of yang.

Eventually in the novella, thanks to the tenacious efforts of that young gynecologist Xiao Sun, who inhabits the borderline of the yin-yang worlds and can travel freely between the two, Wang Er cures his impotence and has no reason to continue living in the basement. He returns to the yang world aboveground, marries Xiao Sun, and leads a normal but constrained life. The ending seems to suggest that the freedom in the yin world, however limited and latent, has its cost. Wang Er can only live a free underground life in a compromised state of undernourished yang. There is no real solution to the dilemma except for traveling back and forth between the two worlds.

Twenty-four years have passed since Wang Xiaobo’s death in 1997, yet the Chinese public’s passion for this literary outlier has only grown stronger and deeper with each year, a phenomenon that still puzzles many readers and critics. Why would so many readers in China love a writer so uncharacteristic of China? Every time I wonder about this question, I can’t help but think of a comment made by professor and critic Ài Xiǎomíng 艾晓明, who was among the few scholars to first recognize Wang Xiaobo’s literary and intellectual value and remained a dedicated promoter of his writings. In her afterword to the memoir that she and Wang Xiaobo’s widow Li Yinhe co-edited, The Romantic Knight: Remembering Wang Xiaobo, Ai Xiaoming quotes an idea about books from Jorge Luis Borges to explain the Wang Xiaobo phenomenon. In his essay “On the Cult of Books,” Borges writes of how each country chooses to be represented by a book that is usually not characteristic of the country. For instance, Shakespeare is undoubtedly the most famous English author, yet none of the typical English characteristics of reserve and reticence are found in him. Shakespeare flows like a great river and abounds in hyperbole and metaphor. In Goethe’s case, while Germans are easily roused to fanaticism, Goethe is a very tolerant man who even greets Napoleon, the notorious invader to his own country. Borges concludes that it seems as if each country looks for a form of antidote in the author it chooses.

Perhaps people in China are seeking in Wang Xiaobo something they lack. His rationality and emphasis on individuality, his pursuit of knowledge for the pure pleasure of thinking, his playfulness and dark humor all offer something like an antidote to China, a country characterized by its practical and collective mentality, obedience to authorities, and a tendency to be “easily roused to fanaticism.”

With nationalism and fanaticism on the rise today, China needs an antidote like Wang Xiaobo more than ever.