This Week in China’s History: April 26, 1989

Of all the momentous events that took place in China in the spring of 1989, perhaps the most pivotal was a newspaper editorial that appeared on April 26 and came to be known, simply, as “the April 26 Editorial.”

It had been a turbulent April. Former Communist Party General Secretary Hú Yàobāng 胡耀邦 had died on April 15, and in the days that followed, mourners gathered in Tiananmen Square. It was not common for young people, especially, to mourn the passing of former CCP officials, but Hu had supported reform and democratization in the 1980s at the cost of his career, and for those he had supported, the least they could do was publicly grieve his passing and lobby for his legacy.

Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 himself had handpicked Hu Yaobang and overseen his rise to the highest position in the Party, where he helped manage the turbulent implementation of economic reforms. When, amid economic uncertainty and political stasis, university students in 1986 began protesting — their wide-ranging demands included curricular changes, electoral reforms, and campus improvements — conservative officials in the government called for swift and decisive intervention. Even though the protests ended after a month, with little violence and few apparent effects, Hu Yaobang was blamed for having permitted dissent to linger. Hu was lionized by students and reformers as a hero, but stripped of his position as Party General Secretary in January 1987.

When Hu died unexpectedly just two years later, the protests that erupted were not simply about grief or remembrance. Hu Yaobang’s fall had threatened the pace of reform. His rehabilitation would be important for reform advocates, but that rehabilitation would have to come from the top: Deng Xiaoping. Perhaps Hu’s untimely death could be an opportunity for reappraising Hu’s career and reinvigorating the possibility of greater reform. A public reminder of Hu’s role might help ensure the reforms he had supported.

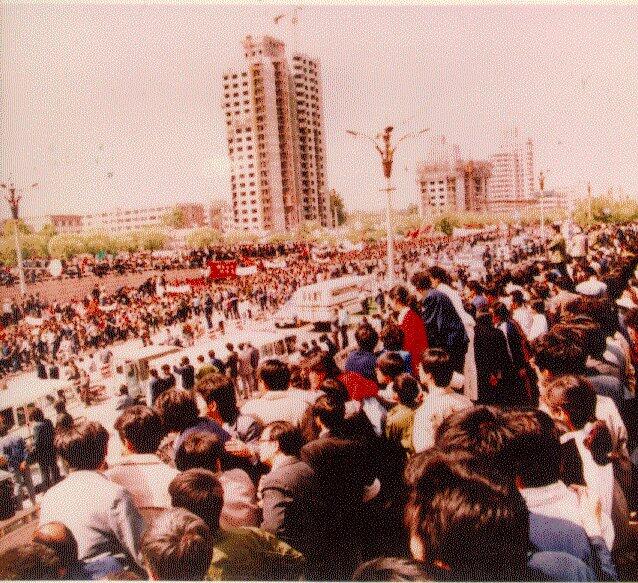

So, students assembled with their banners and photographs at the Monument to the People’s Heroes, an obelisk centered among Tiananmen’s imposing symbols of power: the gate to the Forbidden City that gives the square its name, the Mao Zedong mausoleum, the Museum of the Revolution, and the Great Hall of the People, housing the legislature and many ceremonial halls. Hundreds, then thousands, of people gathered daily to remember Hu and to pressure the government.

April 22 was designated for Hu’s memorial service. In anticipation of a protest, demonstrations were forbidden and Tiananmen Square was to be kept empty, but students arrived before police cordons were erected, and some 50,000 students held a vigil in front of the Great Hall of the People while the official ceremony took place inside. In a poignant symbolic gesture, a small group of students knelt before the Great Hall holding a list of grievances for the premier, Lǐ Péng 李鹏, to receive. This form of petitioning the government had long been a prerogative of Chinese citizens and subjects, especially students, but it was no surprise that Li refused to come out and receive the students’ manifesto.

By this point, the protests had already exceeded the demonstrations that had led to Hu Yaobang’s ouster three years prior, and with each passing day the possibility of real change grew stronger. Zhào Zǐyáng 赵紫阳, Hu’s replacement as General Secretary, was himself a reformer, known to disagree with Li Peng. And, in just a few weeks, the Chinese leadership would welcome Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev to Beijing. Gorbachev was not just a reformer, he was the reformer of the communist world, and his coming was celebrated by many of the Chinese students. Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika (opening and reform) seemed to spell an end to — or at least a softening of — authoritarian Communist Party rule in the Soviet Union. The visit to China would end three decades of Sino-Soviet conflict; perhaps the two Communist giants would move jointly toward greater political openness?

But the landscape shifted dramatically on April 26 (actually, the evening of the 25th, when the next day’s front-page editorial was broadcast on the nightly news).

People’s Daily editorials had a tradition of representing the views of the leaders. Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 famously called on his followers to “Bombard the Headquarters” using this format in the Cultural Revolution (though it had first appeared as a wall poster), but that is just one example. State leaders rarely made official statements or public proclamations; People’s Daily editorials filled that role. After weeks of uncertainty and growing optimism, the front-page editorial, titled “We must resolutely oppose disorder,” made clear the leadership’s position. The People’s Daily declared that the demonstrations had been manipulated by “an extremely small number of people” into a “conspiracy…to plunge the whole country into chaos.”

Such a statement could not appear without the explicit approval of Deng Xiaoping himself. Importantly, Zhao Ziyang, the most powerful reformist voice in the Party leadership, was out of the country when the editorial appeared, on a state visit to North Korea. With Zhao away, hardliners led by Li Peng were able to sway Party opinion, including that of Deng Xiaoping.

The editorial was formally supportive but patronizing of the students’ desire to mourn Hu, and applauded them for their patriotic spirit and commitment to the Party while also praising them for not disrupting the memorial inside the Great Hall. The time for gatherings, it announced, was now over.

“The broad masses of students sincerely hope that corruption will be eliminated and democracy will be promoted,” the editorial stated. “These, too, are the demands of the Party and the government. These demands can only be realized by strengthening the efforts for improvement and rectification, vigorously pushing forward the reform, and making perfect our socialist democracy and our legal system under the Party leadership.”

Whereas many protesters saw themselves as patriots working toward a stronger and better China, the editorial was clear in its view of the protests that continued after Hu’s funeral: “Their purpose was to sow dissension among the people, plunge the whole country into chaos and sabotage the political situation of stability and unity. This is a planned conspiracy and a disturbance.” The People’s Daily called on the people of China to oppose the protests. Further “unlawful parades and demonstrations” were forbidden.

The response was immediate and overwhelming. On April 27, outraged by the editorial, students from campuses all across Beijing marched toward Tiananmen Square. Police lines formed to stop the marchers, briefly halting their progress. Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon’s film The Gate of Heavenly Peace shows tense, then joyous moments when the students confront and then peacefully break through police lines, with many officers smiling approvingly. By day’s end, hundreds of thousands of protesters had filled the square. Buoyed by their successful march in defiance of the government, protesters looked ahead to May Fourth, when students had rallied in 1919 to “save the nation” from imperialism, and then the planned arrival of Gorbachev on May 15. By then, a million people packed the square. With a thousand students on hunger strike, Li Peng finally agreed to a meeting with student leaders on May 18.

The April 26 editorial, surely, had been refuted? Reform was around the corner.

It did not work out that way. While students celebrated and their numbers surged, the government response slipped steadily, inexorably, toward violence. Gorbachev’s arrival might have been an exit ramp, but no compromise could be reached. The meeting with Li Peng went badly. On May 19, Zhao Ziyang appeared in the square, distraught, and urged students to end their protests. The next day, martial law was declared. It took two weeks for soldiers, opposed by the people of Beijing, to reach the square. They arrived in the early hours of June 4.

It is June 4 that the world remembers as the culmination of the 1989 Beijing Spring, when six weeks of protests ended in violence. But April 26 may have been the point at which the die was cast. Before that date, progress and reform seemed possible; afterwards, the opposing sides fulfilled the worst fears of the other. The protests moved away from compromise; the government moved toward murder.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.