Spirituality and politics inside a Chinese Buddhist temple

In China, Buddha is back in business. But for those who run Buddhist temples, there’s a fine line that is walked between worship and politics.

“If our daughter gets a bad score on her college university entrance exam, what should we do?”

The family had driven over 100 kilometers from Shanxi province to the middle of nowhere in Hebei province to ask this question. (The closest big city was Zhangjiakou, which will co-host the 2022 Winter Olympics alongside Beijing, about an hour’s drive away.) They knelt before the master of Henan Temple (河南寺 hénán sì), mother, father, daughter, all awaiting his answer.

Master Zheng, who reconstructed Henan Temple after three decades of disrepair, sat on a polished rosewood chair with his legs crossed in lotus position under his robes. He smiled a bit and laughed before he spoke. “She will do well. I can tell that much is clear. You should not pressure her too much. You must believe in your daughter.”

I sat on a chair just two meters away and watched this unfold, trying my best to be inconspicuous. Ten days earlier, I had arrived at the temple after a full day of motorbiking into the wild winterscape of the deep Hebei countryside, hoping to get an immersive experience in Buddhist temple life in contemporary China. Over the next two weeks, I would get much more than I had bargained for.

“Why did you want to come here?” Master Zheng had asked me when I showed up in the temple’s greeting hall.

“I want to study Buddhism and the ways of your temple,” I replied.

He cocked his head to one side. “Well, are you a Buddhist?”

“No. I am interested in Buddhism and I want to see it for myself.”

“Let me make this clear to you now.” He leaned toward me under the light of a single LED bulb in the southern hall of the temple complex. “No sex, no drinking, and no speaking during meals!” The master paused for a moment. “Do you agree to these rules?”

I nodded.

My assent caused him to smile, which immediately gave him the likeness of none other than the laughing Buddha himself. Under the dim lights I could see his bald head, blue robe, and a prayer-beaded necklace, which had to be at least two meters long, beset with hundreds of wooden beads, each the size of a ping-pong ball.

“Guopeng!” the master yelled. “GUOPENG!”

A young man emerged from the wooden door. “Master! Amituofo!” He bowed.

“Can you show our guest to his room? Tomorrow we continue our conversation.” The master laughed. “And make sure he joins our WeChat group!”

Guopeng led me through the temple to a concrete house with bedchambers for guests and the young monks. The chamber was fitted with two beds stacked against the walls and a desk with Buddhist teachings which had been left by former residents.

As far as temple retreats go, this would be a bad one. The Buddhism that was cultivated here was for long-term consumption, and not ideal for a weekend spiritual experience. But then again, I had not come here for leisure. I wanted to experience Buddhist temple life in modern China.

This was just before the start of Spring Festival in 2019. Two weeks of assisting in temple operations — and preparing for celebrations for the big national holiday — would teach me about the people who choose to live in a monastery, the local politics of Buddhist temples, and the spirituality that lingers, even prospers, in the Chinese countryside.

A temple of destruction and rebirth

Henan Temple — also called Amitabha Temple (弥陀寺 mítuó sì) — is nestled in the sharp hills of northern China. It lies between the major cities of Beijing, Zhangjiakou, and Datong, and the sacred Buddhist mountain Wǔtáishān 五台山. Since its founding in 1141, it has been destroyed and rebuilt several times: during the Yuan dynasty, the Qing dynasty, the warlord era in the 1910s, and again during the Cultural Revolution. Destruction seemed to be a condition for the temple’s existence — as did rebirth. This had been the way for centuries, and so it was again in 2006 when a monk walked into the hills of Hebei to build it anew.

“When I studied at Tsinghua University in the 1980s, my teacher told me that there was a lot of culture that needed to be restored,” Master Zheng told me. “I was studying ‘culture,’ can you believe it? Back then, the major was just called culture. My teacher said each of us could go into the provinces and build up the temples and shrines again. And that is what I have done.”

After Zheng graduated from Tsinghua, one of China’s most prestigious universities, in 1987, he ventured to Mt. Wutai to commence his Buddhist studies. In 1998 he underwent the “ordination of the three platforms” (三坛大戒 sān tán dà jiè) at the famed Bishan Temple (碧山寺 bìshān sì) at Mt. Wutai, thus taking his place as a member of the higher Buddhist clergy. In 2006, by invitation, he became the abbot of Qingliang Temple on Huangyang Mountain in Zhuolu County, Hebei. While living there, he discovered the location of Henan Temple, which had withered away to only a small brick cabin. Today, thanks to Zheng’s efforts, that cabin serves as the master’s audience hall. It took more than 10 years to reconstruct the temple.

“We are a temple of the old ways,” Zheng said. “Everybody is welcome here, and we don’t charge them anything for food or accommodation. We always invite the villagers to come eat with us if they have time.”

Buddhism is China’s major religion, but the number of practicing Buddhists in the country is unclear, as the government doesn’t overtly encourage the growth of religious activities. A 2020 report by the Council on Foreign Relations estimated that about 16.6% of China’s population adheres to Buddhism. But in terms of actual believers, the numbers are fuzzy. Freedom House estimates that there are anywhere from 185 million to 250 million Buddhists in China. This wide discrepancy is due to the fact that many Chinese practice more than one religion. In many Daoist and Buddhist temples, you can find gods from both religions. Most sources agree that there are approximately 120,000 Buddhist clerical personnel (what we might call monks) spread across 28,000 temples and shrines. This number is excluding Tibetan Buddhism, which has roughly six million followers, largely concentrated in Tibet, Yunnan, Sichuan, Qinghai, and Gansu. Master Zheng’s followers largely hailed from Hebei, Shanxi, Beijing, and Inner Mongolia.

Eat your own prosperity

Tap, tap, tap.

It was 6:30 in the morning.

Tap, tap, tap.

The sound of a blunt wooden instrument knocking on bricks rang through the temple yard. The call for breakfast. I hurriedly put on my clothes and made my way out the door. The cold was bitter and darkness still engulfed the temple. I entered the dining hall through a side door. The main door was reserved for monks.

Seven monks, six aunties who worked the kitchens, and seven initiates sat quietly and waited. The frost lingered. I was shivering in the morning cold. Don’t talk, I told myself. In the middle of the hall stood a large Buddha statue. Red ribbons with names scribbled in beautiful calligraphy hung from the Buddha’s hands, folded in prayer. Two rows of tables were evenly spaced from the middle of the room toward each end. The hall could probably hold 50 people at a time. That morning, there would be only 22 of us.

Only when the master appeared did the morning ritual — and the meal — begin. Master Zheng pulled a thick plastic-and-cotton curtain to the side as he entered the hall. When he sat down, one of the monks began chiming bells, and just like that, the hall was inundated with prayer. I did my best to mimic the prayer. One of the young monks took a small bowl of rice and placed it before the Buddha in the middle of the hall. With two miniature gold utensils — resembling a sword and a halberd — he scooped out a bit of rice, took a step backwards, bowed to the Buddha, then left through the main door into the dark frosty morning.

Guopeng sat next to me. He pointed to the end of the room where food was now being placed. The men hurried to the buffet, as they are served before the women. Gender equality has not found its way to the temple yet. The food was rice porridge and millet soup with steamed buns and a variety of pickles and sweet buns, with bean paste on the side. All vegetarian. Feeling that he had to take responsibility for me, Guopeng gestured with his head and hands how I should eat. Without making a sound. Straighten your back. Sit closer to the table. Pour water into your bowl to free the last remnants of the food to be consumed.

After the meal, when the master left the chamber and the silence was allowed to be broken, I placed my bowl with the rest of the dirty dishes. One of the aunties came to me with the bowl in her hand. She pointed to three pieces of rice in the stainless steel bowl. “This is your fú 福,” she said. “Your prosperity. You don’t want to waste it, do you?”

The dwellers

The master left the dining hall and stepped into a black Volkswagen waiting in front of the temple. He put on black sunglasses before the car took off — off to visit, I would learn later, “the important people.” I was assigned practical duties with Guopeng. Sometimes sweeping the temple yard, sometimes shoveling coal for the furnace, or washing the floor of the temple halls.

After a couple of days at the temple, I found that monks and initiates alike all had their reasons for being there. Guopeng had been hit by a bus in the Inner Mongolian city of Ulanqab. After weeks in the hospital, he was released to his family, but he was not the same, and deemed unfit to work. “After the accident, something was wrong with my brain,” he said.

“Do you always tell people this story?” I asked, suspecting he told everyone because he believed it defined him.

He nodded.

“I don’t think you need to,” I said. “You’re a great guy.”

One monk, who was often charged with important tasks such as garbage collection and securing food supplies, told me he spent some three years in a Hebei prison before he was released and became a Buddhist monk. When I asked him what he had been detained for, he displayed a slightly embarrassed smile before demurring. “Now I have a new life,” he said.

Someone else that I befriended, who worked the temple furnace and kept incense piles replenished, told me he and his wife were there because of their daughter. “I am not a Buddhist,” he said. “Or, I wasn’t, but my daughter is. She is dying.” He said it in a very matter-of-fact tone. “The hospital said there was nothing more to do. She wanted to come here to the temple, so my wife and I visit her when we can.”

Local politics and “the important people”

One morning, I found myself washing the floor of a building that I hitherto had not been allowed to enter. It was close to the main temple building and had a small courtyard with a pavilion and table arrangements. Guopeng unlocked the door. Inside was a large room — like a conference room — and on the wall hung two large portraits: one of China’s current president, Xí Jìnpíng 习近平, and next to it, a portrait of Máo Zédōng 毛泽东.

“What is this room for?” I asked Guopeng.

“The master can receive guests here,” he replied.

We began scrubbing the floor.

“Do you know where the master goes when he drives to town?” I asked.

Guopeng smiled and laughed. “He goes to visit the important people.”

Master Zheng had built up a web of contacts whose relations he kept close. Of foremost importance was this trifecta: the Zhangjiakou Buddhist Association, Zhangjiakou Religious Affairs Committee, and the United Front Work Department (统战部 tǒngzhàn bù).

The Buddhist association was important for reasons of religious legitimacy. This organization determines what temples are deemed as adhering to orthodox Buddhism and which aren’t. Master Zheng had previously been the vice chairman of this organization, and he kept in touch with prominent members. The religious affairs committee was in charge of issuing many of the permits that the temple needed to operate. The United Front Work needed to be shown that the temple was actively contributing to society and helping implement key policies that were of interest to government officials.

Keeping up political graces allowed the temple more room to maneuver as a religious organization and enabled the prospect of future expansion. Henan Temple was an example that religion was alive and kicking, but it functioned within the secular context of helping people from surrounding villages. With political relations secured, Master Zheng was now trying to build a new temple in the nearby Shanxi coal town of Datong.

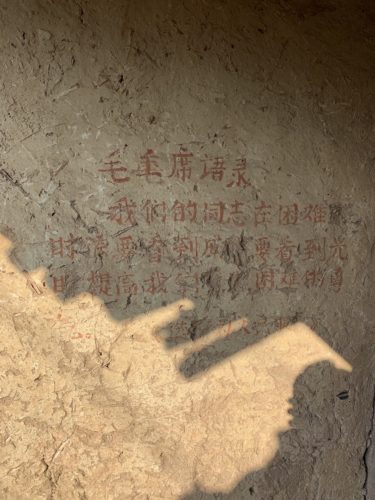

Later that day, Guopeng and I wandered out into the villages. Xiyaogou was an ancient village built around a fire-signaling station and Ming dynasty forts designed as early warning posts on the expanded Great Wall. Most of the houses were abandoned. The Ming and Qing architecture were laid bare to nature. “Revolutionary Site” (革命旧址 gémìng jiùzhǐ), read characters on a concrete boulder. In Xiyaogou, Nationalist troops had engaged Japanese soldiers during the Second World War. Later, the hills proved ideal for Communist ambushes. We wandered through the ruins of the old village. The remains of Cultural Revolution propaganda could still be found on some of the walls: “In times of difficulty we must not lose sight of our XXXX” — some of the Chinese characters were scratched out. (Achievements was the missing word, I later found through Baidu.) “See the bright future and pluck up our courage,” it continued.

“You could easily rent one of these houses if you wanted to,” Guopeng said. The houses were old, some of them on the brink of collapse. A few were traditional cave dwellings that can be found all over northern China. They still have traces of the paper that used to guard the winds from entering into the living space between the woodcut window frames.

“Tuopinle!” Guopeng said as we wandered through the ruins: “Pulled out of poverty.”

The other side of Jupiter

That evening, I got an invitation to the private quarters of monk Jing. He was 32 and had studied at a temple in Zhejiang province before coming to Henan Temple. A young and independent fixer for Master Zheng, Jing understood Buddhism outside of the temple, and he had become a valuable monk for the master, to the extent that he was a potential successor. “I was 15 when I became a devout monk,” he said. The phrase he used was chūjiā 出家, literally meaning “to leave home.”

“Have some tea,” Jing offered me. We sat on the floor of his living quarters, a small room with few things. A foldable futon, a tea table, and a closet for robes. Two women, one who looked like she was in her 40s and the other who was half her age, joined us around the tea table.

“There are truly awesome depths to Buddhism,” Jing said.

We drank tea, and kept on drinking until I felt lightheaded.

“Do you ever have existentialist thoughts?” he asked.

“Frequently,” I answered.

The middle-aged woman smiled while the younger one did not.

“There are many things you can see when you get deeper into Buddhism.” He began gesticulating. “For example, I can be here together with you, right now, and be on the other side of Jupiter.”

“The planet Jupiter?” I asked.

“Yes. Once you realize that your body is only the holster for the soul, you can move anywhere.”

The young woman to my left looked skeptical. “Is that what you say when you take the money away from people who come here?” she asked sharply. The existentialist session ground to a halt. Monk Jing looked at her, his expression asking for elaboration.

“I am not a Buddhist myself, but I have come here because my mother wanted me to,” the young lady said. “Isn’t it true that some Buddhists say men are better than women? That you must have done bad things in your previous life if you are a woman in this one? What nonsense.”

Slightly taken aback, the monk replied, “We can only help those who come here of their own free will. We ask for money only to sustain our temple and to help our followers.”

There are stories throughout China of temples that have embezzled money or charged large sums for believers, like the Catholics with their indulgences, while monks lived in luxury. It did not strike me that the monks of Henan Temple or Master Zheng were living opulent lifestyles, though signs of money flow were evident. One morning, Guopeng and I were washing the floors when I found a portrait of a middle-aged man in a black suit behind the most sacred altar in the main prayer hall. Guopeng explained that this was one of the biggest real estate developers in Zhangjiakou and that he had once come with about a hundred employees to be blessed by the Buddhists. The real estate developer donated tens of thousands of yuan to the temple. Guopeng pointed to the picture and said, “He is very powerful.”

Back in monk Jing’s quarters, I tried talking to the young woman. “I don’t know why I feel like this,” she said. “I guess it is because my mom always dragged me to these temples, and it was only when I realized I did not believe in any religion that I could make up my own mind. I guess many people do believe. While others may just be following the flow of the river.”

The Spring Festival Ritual of pufo

Starting on the first day of the Spring Festival holiday, my eighth day, the temple buzzed with energy. There was sweet puffy cake with loads of sweet whipped cream served as dessert at breakfast. Master Zheng caused roars to roll through the dining hall when he put whipped cream on his eyebrows and posed while monks and followers snapped photos. For lunch the kitchen aunties prepared hotpots, which were only used on rare festive occasions. And there was no occasion more festive than this one, celebrating the new lunar year.

The púfó 普佛 ritual began after breakfast, as practicing Buddhists from across the region began to arrive. During the ritual, people in the public get a chance to direct questions to Buddha, i.e., ask the master for advice on important life matters one-on-one. After asking the master, they would go to the office of the regular monks to have the question written down on a red piece of paper, to be sacrificed via burning during the New Year High Mass later that day. Afterwards, the person’s name, address, and city would be written on a red ribbon and placed on the Buddha in the dining hall, which we prayed to at every meal.

Every day during the weeklong Spring Festival holiday, people came to attend the high mass. I asked Master Zheng if I could sit in on a pufo session and listen to the questions that people posed. It was a longshot, but for whatever reason, the master said yes.

“I am from Zhangjiakou,” one man said. “I work as a taxi driver. I don’t have anything more than a Buddha dangling from my rearview mirror and my prayer beads to show for my religion. Except, every year, I come here.”

A village party secretary asked the master what to do about a misunderstanding with his superior, which could potentially lead to a loss of face for the both of them. “You have to ask the superior’s superior to sort this out,” the master advised. “It is important that you ask him to find fair terms for you and the other party. Otherwise he will hold a grudge.”

After everyone left, I asked Master Zheng how he felt about giving advice. “I pray to Buddha,” he said. “It is easier to sort people’s problems when you are on the outside. They carry half the answer within themselves.”

I walked outside. More people were arriving, and the temple that normally held 22 people now accommodated 150 every day. “Mom and dad! This is my foreign friend!” Guopeng said while his parents climbed the temple steps to where I was standing. I greeted them.

I stuck out like a sore thumb in the crowd, which the monks seemed to use to their advantage. “Mr. Xing, this is the young man who has come to study Buddhism at our temple,” Master Zheng said to the vice secretary of the Zhangjiakou Religious Affairs Committee. Then came the general secretary of the Zhangjiakou Buddhist Association, and lastly the assistant head of the United Front Work Department, who all had their turn talking privately with Master Zheng.

The last people I was introduced to were two officials from Datong, who were also courteously received by the master. Master Zheng has taken up the position of vice chairman of the Buddhist Association of Datong because plans to construct a temple there were moving forward. Later, pictures of the Datong temple construction were posted in the Henan Temple WeChat group.

“Amituofo, amituofo,” everyone started chanting. The prayer hall was packed with people. The master unfolded a red piece of paper. “Wang Zhen.” We kept the chant going. A person walked from the crowd and stood beside Master Zheng. The master lit the paper and a monk rushed to help burn the paper in a steel vat. Embers to ashes. The monks helped scoop the ash into a plastic bag. “Xing Ruoer,” the master called. He called about 20 people in this one session alone.

Afterwards, I met with monk Jing. “They have to spread the ash close to their house,” he told me. “Preferably in a stream or a lake. They also get a golden bedsheet that they should put under their sheets at home.”

After the pufo session with the Shanxi parents who were worried about their daughter’s college examination test, the family of three walked away. Master Zheng and I sat quietly. All of a sudden, the door opened again and the young girl, about whom the question had concerned, came running back into the hall in tears. “Master! Master!” She fell down before the master’s chair. ”I really want to go to America to study at university there, but I did not dare tell my parents.”

Master Zheng smiled slightly with a hint of compassion. “Then you should go.”

She stopped crying and wiped the tears from her eyes with the back of her hand. “Thank you, Master,” she said.

“It is always better to go out and see the world. Tell your parents that I have told it to be so.”

The next day, I bade farewell to Master Zheng, monk Jing, and Guopeng. Over the next year, I periodically checked in on the progress of the new Datong Temple. Jing had been dispatched to oversee its construction. It was completed in the late spring of 2020, just as the country opened up after the first wave of COVID-19 subsided.

The master also sent me a picture of the Buddha in the dining hall, which was covered in hundreds of red ribbons. There, the monks prayed for the people and their wishes. The ribbons carried the names of all the Buddhists who had spoken to the master, as well as the various association heads who had visited. Among them, one ribbon carried the name — written in beautiful calligraphy — of that young girl from Shanxi. The master is no fortune-teller, but with his blessing, it’s possible that she may have found the courage, on that frosty day in the middle of nowhere in a Hebei temple, to change her life.