The Reciter: A Uyghur family’s pride — and downfall

Nurali, after memorizing the Quran, brought immense pride to his family. But back home in Xinjiang, his mother, who financed his studies, was accused of abetting "terrorism," and sentenced to 16.5 years in prison.

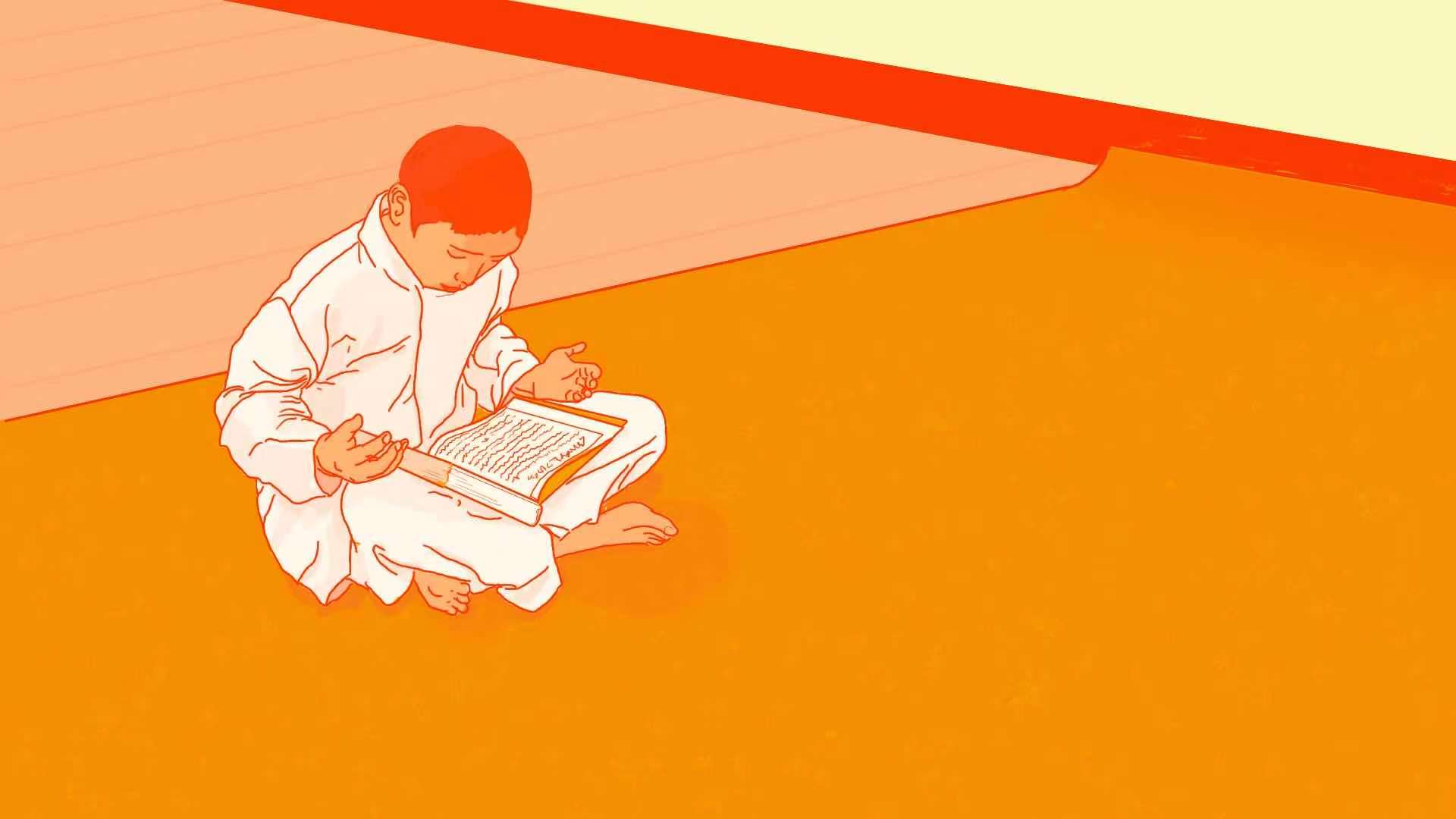

It took him three years, but finally, at the age of 14, Nurali recited the entire Quran. This, he remembers, was one of the happiest days of his mother’s life. Over the phone she told him how proud she was. How he had brought so much joy and honor to his family. He was a living Quran, his life itself part of a sacred tradition that had been passed on for centuries. Now he became Nurali Qari — Nurali the Reciter.

Nurali was living with his aunt in Cairo at the time, far away from his Uyghur classmates — whom he had last seen at his 10th birthday party at the fanciest restaurant in Ürümqi. The restaurant, Herembagh, was famous for upscale Turkish-style Uyghur cuisine. The waiters wore white gloves and everyone drank tea out of tiny tulip-shaped glasses. But that isn’t what Nurali remembers. Instead, he recalls the toys that the other kids showered on him and how he was the apple of his mother’s eye. He was a young boy on the cusp of a massive adventure, preparing to embark to Cairo, a city he knew only from his imagination. He was going to become a reciter near the center of the world. Everyone was proud of him.

He did not know that his pursuit of something that would make his mother so happy would result in an Interpol “red notice,” Chinese authorities deeming his family members “terrorists” — and, for his mother, a 16-and-a-half-year prison sentence.

Among Uyghurs, Quranic recitation is a centuries-old tradition. The honorific title “qari”is added to the name of young men who learn to recite, or whose parents aspire for them to become a reciter. In fact, in some areas of Southern Xinjiang, many boys are referred to as qari whether or not they actually have that formal training. The primary reason Uyghur families sent their children to study the Quran was to strengthen their faith, but it also signaled respectability. As the Uyghur intellectual Abduweli Ayup told me in a recent interview, “If your son or daughter could recite the Quran, people thought that they would be able to find them a better marriage partner. It was something that gave people status.”

Ayup spent time in a detention center near Kashgar in 2015 at the start of the People’s War on Terror. “Even in the detention center, a person would be treated better than others by the Uyghur guards if they were a qari,” Ayup said, laughing at the incongruity. “Because the person had become kind of sacred, it offered them some protection.” Mistreating a qari was tantamount to mistreating the Quran itself.

As a reciter became older, others would often add more honorifics, such as qarihajim, or “reciter of the Quran and pilgrim to Mecca.” They did this regardless of whether or not the person had actually gone on the Hajj — something that was tightly controlled by the government. The sacredness of the knowledge the person carried meant that it was as if they had walked in the footsteps of the Prophet.

Most Uyghurs know someone who is a qari or is said to be one, but fewer and fewer born in or after the 1990s receive formal training from a master of recitation. This is because, after the state violence in Ghulja in 1997 and the subsequent banning of informal instruction in Quranic education, recitation training is often done in secret or with the aid of a recording.

During the early 2010s, devices called qelim qari, or “pen reciters” — devices that allow students to listen to and practice particular surah or verses of the Quran — were manufactured and sold by Chinese-based companies via Alibaba. Others bought MP3 recordings that carefully laid out the correct intonations, or tajwid. These self-instruction devices cost only 200 or 300 yuan ($31 to $46) and were available in nearly every large market, promising a way of continuing the recitation tradition without having to depend on underground schools. Although these devices continue to be sold in China, particularly within the Hui community outside of Xinjiang, among Uyghurs and Kazakhs in Xinjiang, possession of such devices is frequently criminalized as a sign of “pre-terrorism.”

Yet in Muslim communities around the world, this tradition continues unabated. As University of California Davis doctoral researcher Muneeza Rizvi told me, “In the United States, every practicing Muslim probably knows of someone who is a qari or hafiz of the Quran.” Among pious Muslims in North America and Europe, “it is a marker of dedicated parenting for a child to have completed a recitation program alongside his or her conventional education.” In some cases, Muslim Americans shape their life path to provide this type of training to their children. “For example, a friend of mine, a Black American convert to Islam, actually moved to Senegal just to give her child access to a Quran school in the region,” Rizvi said. “She was very proud to learn about how West African qari safeguarded the Islamic tradition through the horrors of the Middle Passage and among Muslim captives in the Americas.”

Like Muslims around the world, Nurali’s parents and extended family framed Nurali’s learning of the Quran as part of a vital standard-bearing of Islamic traditions. “Generally speaking, Muslims often use language like ‘protect’ and ‘safeguard’ to describe Quran memorization, celebrating the idea that, even if there was a total absence of written copies of the Quran, it would be impossible to eradicate the tradition,” Rizvi said. “I can imagine this would feel especially inspiring and meaningful to Uyghur Muslims experiencing cultural genocide.”

The last time Nurali saw his mother Mehire was in 2015. She came with his father to Egypt after Nurali had been studying the Quran for one year. Mehire visited not only to see her son, but also her sister, Mewlude, who just had a baby.

Mehire was one of four children in her family. She was 15 and her sister, Mewlude, was seven when their father died. Soon after, they moved from Atush, a town near Kashgar, to Ürümqi, where they had a wealthy uncle who had made it big as a trader after market reforms of the 1980s. Mehire went to a university in the city and graduated in 2001. The next year she found a job in the Civil Affairs Ministry neighborhood watch unit (社区 shèqū) in a northern district of Ürümqi. Nurali was born in 2003.

When the protests and violence of 2009 broke out across the city, Mehire began to feel a great deal more pressure to perform her loyalty to the state. Most of the time she was permitted to work in the office, while her coworkers were sent to inspect Uyghur apartments for signs of support for the protests and riots. Their work turned from providing social services to surveillance and grassroots policing. Her boss also began to enforce policies that prohibited religious practice among state workers. This quickly became a problem for Mehire since she wore a headcovering — so she stopped wearing it in the office, but continued wearing it when she was not on the job. (One of Nurali’s earliest memories is of his mom taking off and putting on her scarf. “She could do it so quickly,” he recalled.)

But this was not good enough. People in the community still saw her wearing her headscarf elsewhere. Her boss at the Civil Affairs Ministry pulled her to the side and warned her to stop wearing it. Not only that, they wanted her to renounce Islam altogether. As a result of this pressure, Mehire began to develop excruciating headaches. Eventually a doctor diagnosed her with an anxiety disorder and she resigned from her position. After 10 years in the unit, she finally felt free to live again.

As the anthropologist Cindy Huang writes in her dissertation on the rise of pious Islamic practice among Uyghur women during this period, many women saw wearing a veil as a way of claiming ownership of their religious practice. The veil was read metonymically as a sign of piety and self-respect. There was dignity in veiling. Many Uyghurs had read the prison diaries of the Muslim feminist organizer Zaynab Al-Ghazali, who was imprisoned by the political regime of President Nasser in 1965 due to the way she organized Muslim women to participate in democratic change — one of the roots of the movement that led to the Arab Spring. The diaries — which were first translated into Chinese in the late 1990s and then into Uyghur sometime later — show how faith and religious practice offer a source of strength in the midst of oppression. More importantly, they, and other texts, showed how vibrant the religious community was in Cairo and at Al-Azhar University, where Al-Ghazali remains an important influence. For Uyghurs and Muslims around the world, Al-Azhar is one of the most prestigious centers of Islamic learning in the world.

Mewlude said that she and Mahire didn’t read these texts from the Egyptian Muslim community themselves, but they were turned onto Egypt by Uyghur friends who had read the texts and who helped them understand the importance of Islamic learning. At the same time as the hard-strike campaigns grew in force in the early 2010s, they, like many Uyghurs, began to look to places like Turkey and Egypt as spaces where they could live in greater freedom.

Mewlede went to Egypt first. She dreamed of studying in Al-Azhar and living in the thrall of the great city of Cairo. She also knew that Egypt was a great place to study. “It cost only a little to live there, so you can really focus on studying and not worry about money,” she recalled. When she first arrived, there were around 2,000 Uyghurs living there and many more Hui. These Chinese Muslims from across China actually paved the way for Uyghurs to enter the community, helping them transfer money, find apartments, and register for classes.

Then in late 2015 and early 2016, for the first time in nearly two decades, the government in China allowed Uyghurs to get passports even if their households were not registered in Urumqi. “All of the sudden Egypt looked like a mini Atush,” Mewlede laughed. “Some of them came just so they could go on the Hajj” — which was still highly regulated. Back in Xinjiang, pilgrimages which were not organized by the government were regarded as a sign of extremism, but that didn’t stop people, especially from Atush and Kashgar.

Mahire made the decision to send her son to live with Mewlede in 2014. Because Egypt was so cheap, relatives abroad did not need to send much money. In order to support Nurali’s studies, Mahire wired around $1,000 every six months. “Even with just $100 to $200, anyone would have enough for a month,” she recalled. “It was so cheap that with one Egyptian pound in your pocket you could buy 10 naan. With just one dollar you had bread for a week. So we didn’t struggle.”

Nurali’s tuition was $100 per month, including room and board. At first he talked with his mom every week. Then, as he became more acclimated and started to pick up conversational Arabic, it became every two weeks, and then once a month. The teachers did not speak Uyghur at the school, so he had to learn quickly. “I didn’t go to that school so that I could become an imam or something like that,” he remembered. “I hoped to go to Europe or the United States after I studied the Quran. My grades were not very good in math, so I thought studying Quran and Arabic seemed like something that would really help me.”

When Nurali started he was only 11 and didn’t really feel like he had much choice. He knew that becoming a qari was something that would bring honor to his family. And that was what was most important.

The trouble began in mid-2016. The police started to call Mahire into the station and ask about Nurali. They told her to “make him come back” over and over again, Mewlude recalled. They said, “He is young and is required to still be in school.” They did not recognize that Nurali was still in school and that every year hundreds of thousands of Chinese citizens send middle schoolers abroad to study.

From others in the Uyghur community in Egypt, Mewlude heard that returnees were disappearing upon arrival back in China, so she decided not to return, even though her family was being pressured by authorities back home. At this time, Nurali was nearly finished with his training as a qari. Mahire stopped sending money, hoping that Chinese authorities would give up.

But this was not the case. Sometime in 2017, just months after Nurali became a qari, Chinese authorities issued a “red alert” on Interpol — which at the time was led by the Chinese official Mèng Hóngwěi 孟宏伟 — for Mewlude and her husband, declaring them “fugitives” (táofàn 逃犯) wanted on “terrorism” charges. Civil servants pasted a “three evil forces family” label on the door of Mahire’s apartment in Urumqi. In one of her final messages that the family received, Mahire said, “Please don’t be surprised if I disappear. No matter how hard I try, I am going to be taken away. Horrible things are happening now. When I walk down the street the neighbors avoid me. They just turn away.”

One night in 2018, the Atush police came to Ürümqi to take her away. “We thought it was just like the other times where they kept her in the police station overnight, but this time it was different,” Mewlude said. “She just disappeared.”

Between that time and December 2019, no one in the family knew where Mahire was. Then someone spotted a notice posted by the Atush People’s Court that read: “On May 13, 2015, Mahire Nurmuhemmed used her bank card to remit 8,650 yuan in financial support to Mewlude Nurmuhemmed and Memet’eli Imam (fugitives suspected of endangering national security) in Egypt.” It said that Mahire had used the services of a Hui man who facilitated support for the Uyghur community in Egypt to send the money. The court document failed to note that, at the time when Mahire sent the money to her sister, she had no idea Mewlude would be deemed a terrorist — the term used over and over in the court document to describe her and other Uyghur students — two years later.

A few months later, another family friend contacted Mewlude and told her that Mahire had been sentenced to 16 and a half years in prison because she had financially supported her son’s studies in Egypt.

Mewlude and the family left Egypt for Turkey in April 2017, since there were signs that it was becoming dangerous to stay there and it became hard to find jobs. In Turkey, they had a bigger community and more opportunities. In July 2017, the police in Cairo began to round up and deport Uyghur students. The students who have returned to China have disappeared.

In Turkey, Nurali is preparing for his college entrance exam. He tries not to think about his mother too much. “It just makes me too sad. Sometimes it feels like more than I can bear.” He tries to cling to the memory of his mother’s happiness when she heard the news that he had become a qari, but bearing the weight of Islamic tradition and the honor of his family is a lot for a young reciter to carry.

When I asked him if he would like to recite a surah for his mother, he chose Surah Ad-Dhuha, the passage of the Quran recited to give comfort to orphans. It says that Allah will protect the orphans and that the community around them will not oppress them or drive them away.

By the morning hours

And by the night when it is stillest,

Thy Lord hath not forsaken thee nor doth He hate thee,

And verily the latter portion will be better for thee than the former,

And verily thy Lord will give unto thee so that thou wilt be content.