It was one of the most important meetings in recent Chinese history. In 1927, Máo Zédōng 毛泽东, with a handful of survivors from the botched Autumn Harvest Uprising, limped into the Jinggang mountains. He was hoping to overcome the forces of the Nationalists (KMT), but with little more military experience than this failed uprising. How lucky he was, then, that he received a letter from the commander of another straggler army, insisting “we must unite forces and carry out a well-defined military and agrarian policy.” The cavalry arrived in April 1928 — not the 10,000 shabby reinforcements, but the man leading them, who would prove as valuable as any army (indeed, he would one day be commander in chief of the Red Army, and then the People’s Liberation Army): a former warlord who had converted to Communism and was one of the most experienced soldiers in all the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership.

In the formative years of the CCP, Mao and Zhū Dé 朱德 are literally joined, known as “Zhu Mao” (some peasants even believing they were one person). Together they forged the Red Army and introduced the guerrilla tactics that would lead the CCP to ultimate victory. “The historical course of the Chinese communist movement could not have been imagined without its two twin geniuses,” asserted journalist Edgar Snow. At first, Mao praised Zhu; later, he just about wiped him from the history books.

Who is Zhu De?

An energetic dynamo, described by Agnes Smedley (who interviewed him, star-struck, in 1937) as walking “bent forward a little” with a “pumping gait,” as if impatient to reach his destination. While Mao was a strategist and intellectual, Zhu was “more of a man of action,” and also “more of a peasant.” Zhu was a strong personality, able to inspire his men and lead from the front, a good strategist with years of experience.

Zhu came from a poor peasant family, with a “cruel” father, a man who drowned at least five of his siblings (according to Zhu himself) because they couldn’t afford to keep them. The family was under the sway of a hated local landlord, who Zhu claims made his tenants fight and die to protect him whenever bandits came to town.

Zhu’s great stroke of luck was being sent to school. “Since tax collectors, officials, and soldiers respected or were afraid of educated men, my family decided to send one or more sons to school,” he told Smedley.

Education brought struggles and bullying (wealthier boys relishing the similar sounds of zhū 朱, Zhu De’s surname, and the word for “pig” 猪, pronounced exactly the same), but also an awareness of the outside world. Whereas his family believed tax collectors, landlords, and officials were the enemy, he listened in horror about defeat at the hands of the Japanese in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894, and the destruction of the noble Boxer Rebellion. When traveling in Europe later, he would see Chinese treasures in his host’s houses, knowing they must have been looted by the awkward looks on their faces when he asked how they had acquired them. There was no doubt China was a weak country, requiring a rekindling of what he told Smedley was the innate “tremendous strength, bravery, and fearlessness of the Chinese people.”

Although initially destined for the civil service, the scrapping of the imperial examinations in 1905 set Zhu De on a course of Western schools, learning previously unknown subjects like physics, chemistry, athletics, and Japanese. He enrolled in the Yunnan Military Academy in 1909 — Zhu claimed in interviews he headed to Yunnan to defend the motherland, which was at risk from French dominion. But classmates interviewed later tell a story of Zhu’s aimless meanderings in accounting jobs, washed up in the city before hearing that the local academy was recruiting (much of what Zhu said about his past to Western journalists like Smedley was doctored to fit Communist interpretations).

It just so happened the Yunnan Military Academy was one of the best in the country, basing its ruthless, well-disciplined training on modern army methods learned from the Japanese. Zhu excelled, often chosen to command the cadets whenever men of importance visited. The school was also a hotbed of queue-cutting revolutionaries, convinced the Qing had brought about China’s humiliation. Zhu got involved in the secret Tongmenghui — Chinese United League — a revolutionary society dedicated to overthrowing the Qing, feverishly reading their well-worn pamphlets that he’d hide under his pillow. It helped that his commanding officer and mentor Cài È 蔡锷 was also a member.

When the revolution finally came in 1911, Zhu valiantly played a part in overthrowing the local Qing garrison. Cai E then put him to work patrolling the Yunnan/IndoChina border to weed out bandits. By the time the Beiyang government — the Republic of China government that ruled from Beijing between 1912 and 1928 — turned into a dictatorship in 1916, he was a colonel now opposing the Beiyang army. Those who served under him said he always fought alongside his men at the front, so that his orders could be clearly heard.

As a brigadier general later that year, garrisoned at Sichuan, success had come to Zhu but left him no peace. The revolution had been corrupted: Sun Yat-sen (孫中山 Sūn Zhōngshān) had given up the presidency, and Yuán Shìkǎi 袁世凯 turned into a ruler no different from the ones he had helped overthrow. The Yunnan army had begun to go soft, now occupying Sichuan and engaged in endless skirmishes with petty local brigands for little reason other than growing fat off the wealth of that province.

Even Zhu De had gone soft: He was now addicted to opium. Zhu told Smedley it was out of depression at the political situation, but according to Yang Ruxuan, Zhu slipped into it like many in the Yunnan Army at this time, seduced by Sichuan’s roaring abundance of the drug. He also set about creating his own military power base, with cronies and family in powerful offices and himself at the center.

His secretary, a Peking University graduate, introduced him to Marxist literature. Zhu was fascinated by the Russian Revolution, desperate to work out why they had succeeded where the Chinese had failed. According to his subordinate Yang Ruxuan in later interviews, from 1920 onward he often talked about finding ways to go abroad.

Sun Yat-sen advised him to go to America. But Zhu told Nym Wales (the pseudonym of American journalist Helen Foster Snow) he wanted to see the effects of the Great War on Europe, that Europe was cheaper, and there was the possibility of going to the USSR. Although he was looking forward, he also felt held back: to his horror, he was turned away from the CCP, owing to his warlord background. “Those were terrible days,” he told Smedley. “I was hopeless and confused. One of my feet remained in the old order and the other could find no place in the new.”

He headed to Europe to study German World War I tactics at Göttingen University in 1923, also taking lessons in military theory from a retired German general who insisted (given the hyperinflation) in being paid in Chinese currency. At the same time, he met Zhōu Ēnlái 周恩来, head of the CCP student group, who admitted him to the CCP after a short interview, attending regular evening discussions and co-creating a newspaper. But “everywhere my comrades and I went we were followed by German detectives,” he said.

He was deported by the Chinese embassy in 1925, having been arrested twice. He then spent a year in a Moscow University during the transition from Trotskyism to Stalinism, studying Marxism and Russian theory from teachers fresh from the Russian Civil War. He returned to China in 1926, resuming command in the KMT army. He wouldn’t reveal his true leanings as a CCP member, until the Nanchang uprising in 1927.

Zhu was defeated by KMT forces in Nanchang, and thus limped into the same inaccessible Jinggang mountain range — forming an alliance with Mao Zedong.

Forming the Red Army

The ragtag rabble of stragglers, peasants, KMT deserters, and vagrants had been reorganized into detachments, each with a political commissar and renamed the “Workers and Peasants Revolutionary Army,” of which Zhu was elected the commander in chief. It was ever-recruiting from the peasants in the surrounding countryside, first at the Jinggang Mountain base, and then the Jiangxi Soviet in 1929.

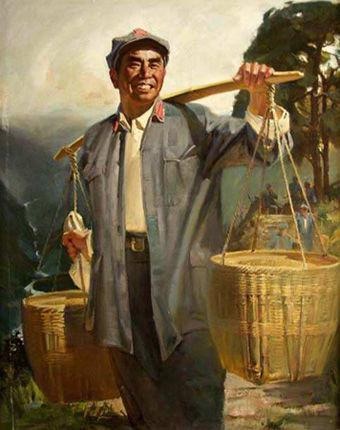

The high mountain ranges of Jinggang proved hard for the KMT to access, but no food could be grown there. This gave rise to a story now famous in the PRC (but with no historical record), of Zhu De regularly walking 50 to 60 kilometers, carrying buckets of rice up steep mountain paths, alongside his men. Fearing for their general’s age and status, his men took away his carrying pole one night, only for him to find a new one the next day, writing “Zhu De’s pole isn’t allowed to be taken randomly” on it.

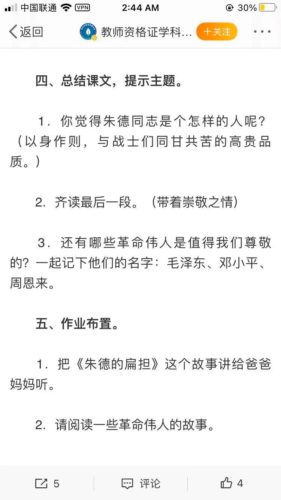

The story is still taught today. A teaching plan on Weibo encourages students to read the story aloud “with reverence,” and also share it with their parents.

When Mao was being criticized by Zhou Enlai and other senior Party figures for his thuggish methods for rooting out spies in the Soviet, it was Zhu who defended him. This would become a regular occurrence: all the way through Mao’s power struggle during the Long March, Zhu proved a firm ally.

At heart, Zhu shared Mao’s ideological fervor but was also a stickler for detail, issuing an article in 1931 titled “How to Forge an Invincible Red Army,” saying that only peasants and urban proles should be allowed to join. Training was ruthless and based on the latest performance assessment systems and American education methods. He knew well the importance of even the smallest details driving the big victories: a shortage of equipment led to numerous directives for soldiers to scour battlefields for absolutely anything of value, even “bullet casings.”

It was Zhu’s experience with bandits in Yunnan, and taking advice from local bandits who had long survived in the Jinggang mountains, that led to his enforcement and creation of tactics for Red Army guerilla warfare. Zhu changed the game by trying to win over locals and pick the enemy off with lightning strikes rather than pitched battles. “We based ourselves on the people,” he told Smedley. “Choosing our own battlefield and keeping the mountains to our back, we drew the enemy where we wanted him, then cut off his transport columns, attacked his flanks, and surrounded and destroyed him.” Academics like Marcia Ristaino (in China’s Art of Revolution) now give Zhu co-credit for the creation of the 16-character phrase that governed the Red Army’s use of guerilla warfare, usually assigned to Mao: “When the enemy advances, we retreat. When the enemy halts and encamps, we harass them. When the enemy seeks to avoid battle (becomes tired), we attack. When the enemy retreats, we pursue.”

Under his guidance, the KMT was unable to encircle the Jiangxi Soviet, despite several successive attempts. KMT forces, marching in neatly ordered columns, were run rings around. It was this combination of flexible guerilla tactics and the disciplined military training of a conventional army, argues historian Stephen Averill, that made the Red Army so effective in the conflicts to come.

And there were many. During the Long March, numerous eyewitnesses described him walking alongside his troops rather than on a horse (but the Chinese government has never let independent historians examine Long March sources, so this shouldn’t be entirely trusted). Zhu considered one of his greatest achievements being to lead the Fourth Army, bruised and battered, all the way to Yan’an after it got separated from the rest of the force.

So the years went by. Zhu commanded the Eighth Route Army during the Japanese War of Aggression, and co-devised the “Hundred Regiments Offensive,” coordinating guerilla warfare to go behind enemy lines and establish bases of resistance. By this point, he was commander in chief of the PLA.

Betrayal

Zhu’s leading role in installing the CCP into power meant he became a living legend. He presided over more than 170 meetings as Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress from 1959 to 1976, and in 1955 became one of the country’s “10 Marshals.” He was the man to lead China’s forces in the Korean War, and be cast as a role model of moral Red leadership: School children would learn about the brave and diligent general, so uncaring of his high position and so concerned for his soldiers that he carried rice up a mountain for them.

But times turned chaotic. Although initially in favor of Mao’s Great Leap Forward, Zhu became rapidly disillusioned by the trips he took out of Zhongnanhai and into the countryside, witnessing the famine brought about by Mao’s shortsighted policies. Like Liú Shàoqí 刘少奇, he campaigned for reforms. From 1958 to 1961, he wrote to the Central Committee demanding an end to disastrous collectivization policies like canteens, backyard smelting, and unrealistic production quotas obsessed with quantity rather than quality.

This, plus his lackluster condemnation of Péng Déhuái 彭德怀, displeased Mao. From 1966, he was publicly criticized by the Politburo, but still stuck to his criticisms — he was a hard man to silence. Jiāng Qīng 江青 argued Zhu wanted to take power for himself. At a session of the Central Committee, his legacy at Mt. Jinggang was torn apart, labeled the “black commander” rather than the “red commander.” Big-character posters were put up at his house in Zhongnanhai, and his wife Kāng Kèqīng 康克清 was made to wear a dunce cap. He was exiled to Guangzhou. Backing from Zhou Enlai ensured Zhu escaped the more gruesome fate of other Party bigwigs who dared to contradict the Great Helmsman.

But instead of taking his life, they took his past. Mao made sure that a biography Zhu had commissioned of his deeds was never published. According to historian Dick Wilson, “it might have suggested that not every single victory on the Long March and at other moments of the Communist struggle was due to the genius of the Chairman.” Shamed by Lín Biāo 林彪 as an “old rightist,” murals of the Mt. Jinggang meeting began showing “Lin Mao” together, while schoolchildren learned about Lin Biao carrying buckets of rice. Lin had been named Mao’s successor, after all, so a hero’s history was required? Zhu took it stoically, telling a family member: “The pole can be lent to him [Lin Biao] for a few days, but sooner or later he will have to return it.” It turned out to be sooner, once Lin was disgraced in 1971.

By 1973, Mao had reunited with his old friend of 40 years. Sitting together on a sofa, laughing and shaking hands, the two octogenarians looked for all the world like firm friends. “If the skin does not exist, how can the hair [毛 máo, also Mao’s surname] be attached?” Mao supposedly punned to stunned onlookers. “How can there be hair without Zhu? Zhu Mao, Zhu Mao, Zhu was first!”

Zhu was first once again in 1976, when he died just two months before his old comrade-in-arms.

Chinese Lives is a recurring series.