Dispatch from Shenzhen: China’s booming drone industry

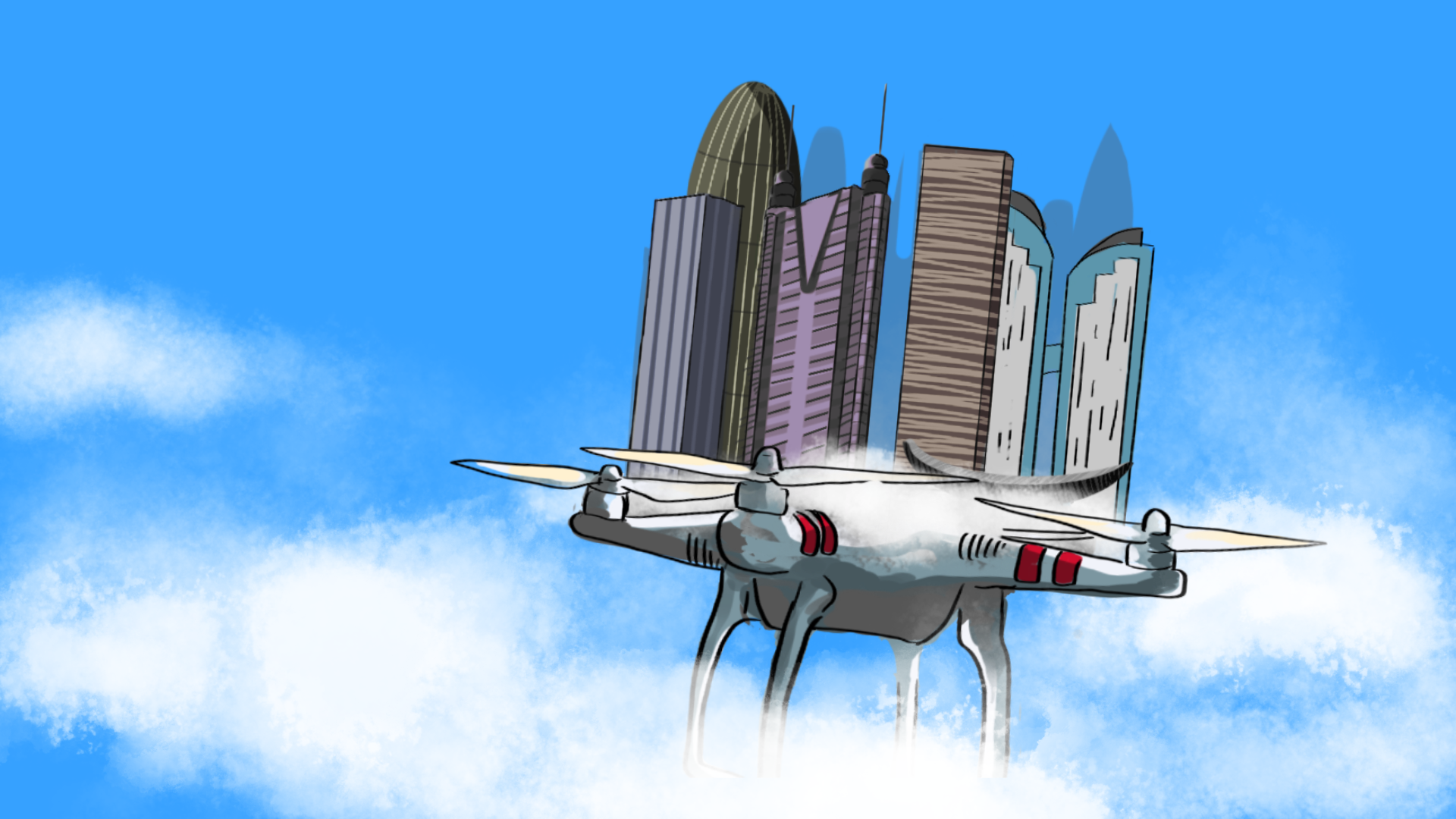

China dominates the global business of consumer and commercial drones, and the buzzing center of this new industry is Shenzhen. The China Project went to this year’s drone expo in the southern city, and this is what we found.

On Saturday, in the heart of Shenzhen’s central business district, the world’s largest drone conference and expo hummed under leaden skies.

A total of 369 exhibitors showcased some 2,000 drone products of an amazing variety. Mini drones the size of a wristwatch hovered next to cargo drones the size of four-seater planes. On the conference floor, drone makers and suppliers mingled and exchanged WeChat contacts. At the booths themselves, some presentations were quite austere, touching on the finer points of public safety and crisis management. Others were purely recreational: At the corner of the exhibition hall, kids played “3v3 drone soccer” to a crowd of adoring parents.

Shenzhen is widely regarded as China’s Silicon Valley. It draws more than a third of its GDP from its burgeoning tech sector and is home to global tech giants such as Tencent and Huawei, along with China’s largest electric vehicle maker, BYD. In recent years, with the global success of homegrown drone maker DJI, it has also earned the title of the world’s “drone capital.” The 6th Shenzhen International UAV Expo, held in a 20,000-square-foot exhibition hall, offered a bird’s-eye view of this fast-growing sector, one that already boasts significant customers in the U.S. Here are some key takeaways.

1. China is and will be the leader in commercial drones

At a modest booth in the middle of the exhibition hall was Shenzhen-based drone behemoth DJI. Despite its commercial roadblocks with the U.S. last year, the $15 billion company continues to control 80% of the global nonmilitary drone industry. (Its closest competitor, Intel, by contrast, holds 4% and does not sell consumer drones but focuses on light shows and other limited uses.)

Among the consumer models on display on Saturday was the DJI Air 2S, a hand-sized metallic gray drone that captures video in 5.4k resolution, more than quadruple that of an average HD movie.

“It’s not just that DJI is the dominant player,” writes 36Kr, a tech blog (in Chinese), “its success is significant in that it’s the first Chinese company to truly lead the world in technology.” Indeed, DJI’s dominance — a first for Chinese enterprises — is not a fluke. Through the 2010s, DJI drones left its competitors in the dust; they were significantly cheaper (estimated at 10% to 20% the cost of U.S. drones), more technologically capable, and more elegant than their American competitors GoPro and 3D Robotics. DJI drones are “by far the most compact drone now available,” writes The Verge. “You can put the [GoPro] Karma into your average backpack, but you can slip the Mavic into something as small as a purse, a water bottle carrier, even a large pocket.”

Behind DJI’s competitive edge is the vibrant city of Shenzhen. Since its days churning out low-end goods at the bottom of the value chain, the city has evolved into an incubator for world-class tech giants with infrastructure, component vendors, hi-tech talent, and low-cost labor all jammed into one place. According to Wáng Diànjiǎ 王殿甲, one of Shenzhen’s deputy mayors, there were more than 80 drone companies (in Chinese) in his district of Nanshan alone last October, creating an annual output of more than $3 billion.

The concentration of drone companies in Shenzhen is ideal for the industry’s global competitiveness and innovation. Cheap drone components such as batteries benefit the whole industry. Meanwhile, human capital — the talent and process knowledge to build drones — transfers easily across companies. Not coincidentally, then, in the years since DJI has dominated the recreational drone market, affiliated industries have also soared. Since 2016, for example, Chinese companies like Shenzhen Damoda Intelligent Control Technology and EHang, both present at the expo, have one-upped their American competitor Intel in the drone light show arena. (Intel’s former world record of 500 drones was trumped by EHang and Damoda using 1,000 and 3,051 drones, respectively, a demonstration of greater technical precision and coordination capabilities.)

The drone entertainment sector has also done something extraordinary: It has drawn the attention of potential new investors who have deep pockets. Since a drone-made airborne QR code by the video-streaming company Bilibili made international headlines last month, China’s vast advertising economy is likely posturing to get in on drone marketing. All of this means the Chinese drone market will be flush with cash even as it competes with already weaker global competitors.

2. The industry is professionalizing as applications grow

Analysts have estimated that more than two-thirds of all drones are purchased for professional purposes. Indeed, most companies at the expo told The China Project they worked with governments and industries rather than selling to consumers. Aside from being more lucrative for early-stage startups, institutions are better equipped to overcome regulatory hurdles. In the U.S., drones that fly in restricted airspace require approval from the Federal Aviation Administration, but users are generally free to fly where they want. In China, there are much stricter and frequently enforced restrictions for individuals that ban drones from being flown above a certain height and near airports, military installations, or other guarded areas such as police checkpoints.

But the drone companies that work with governments, such as in surveillance and public safety, have no issues with regulations.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

One prominent player is INNNO (因诺科技), which was founded in 2015, and bills itself as a Swiss army knife for industry pain points, offering applications for “environmental protection, water conservation, public security, transportation, firefighting, emergency rescue, and others.” (One example, in the energy sector, shows INNNO drones inspecting power lines and towers in a worker’s stead.)

Another player — which had one of the largest booths in the expo — is Shanghai-based AutoFlight, which promises to offer air taxis by 2025. Its helicopter-sized electric V400 Xintianweng drone can hold a maximum of 500 kilograms, and is expected to be used in express deliveries, and for medical and fire emergencies.

3. Industry innovations are happening in software, not hardware

Despite the variety of shapes and sizes at the drone expo, the biggest innovations are now happening in software. One fast-growing drone company, AirDwing, along with its proprietary cloud-based platform, KiteBeam, is quickly becoming to drone software (in Chinese) what DJI is to drone hardware. The Shenzhen-based company works with drone partners, mainly DJI, to offer more sophisticated management tools for governments and industries that want to use a fleet of drones for various applications.

KiteBeam’s software makes it easy to visualize and plan flying routes, coordinate and manage multiple drones, connect them to existing IT networks, and store and analyze data that the drones collect. “AirDwing isn’t just a management tool,” said Jì Hóng 季鸿, the general manager of AirDwing, “it’s a whole planning system for drones that realizes the true potential of the industry.”

“DJI used to want to compete in the software arena, but now they’ve quit and left that mostly to us,” one AirDwing employee told The China Project. This year, the small tech outfit made headlines when it won a contract (in Chinese) to build a drone control system for the Guangdong Province fire and rescue brigade.

In a phenomenon similar to what’s happening in China’s electric vehicle industry, companies like KiteBeam are integrating their software with DJI hardware to make one elegant drone management system. Its compatibility with DJI — the mainstream brand used by U.S. federal agencies, the military, and more than 900 local and state law enforcement and emergency service agencies — gives the company the potential to go global and put its mark on the industry.

“Regardless of how this industry develops, the ultimate goal of AirDwing is to help China have a say in international standards,” said Hong.

4. One million drone pilots needed

DJI said it employed more than 14,000 people in 2019 in a press release, and the number has likely grown since then. Adding in people who work for DJI suppliers and competitors, and all the players in the drone hardware and software industries, there are probably more than hundred thousand people employed in design, coding, and manufacturing.

But there is also rising demand for a new profession: Most drones require experienced human operators, and there is a shortage of them. In April 2019, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security added (in Chinese) “drone pilots” to the list of high-demand professions, estimating that 1 million will be needed in the next three years.

According to a Chinese drone news site (in Chinese), a novice drone pilot can earn $600–$900 a month, while pilots who do a minimum number of training classes and flight hours can get licenses from the Civil Aviation Administration, which can boost their salary to more than $2,300 a month.