The history of Chinese animation, from groundbreaking ‘Havoc in Heaven’ to crappy-looking ‘Kung Fu Mulan’

Nearly 60 years after the release of "Havoc in Heaven," the Chinese animation industry is now struggling to generate revenues at home while trying to expand its presence in the global marketplace. What went wrong?

This article is brought to you by Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, a leading international joint venture university based in Suzhou, Jiangsu, China.

When the lights went down for the first screenings of Princess Iron Fan 铁扇公主 across war-torn China in 1941, audiences were merely eager to see how the country’s first full-length animated feature had turned out. But the film proved to be nothing short of spectacular, heralding the start of a golden era for Chinese animation and laying the groundwork for what would eventually become Havoc in Heaven 大闹天宫 (also translated as Uproar in Heaven), an indisputable classic that has influenced a generation of filmmakers and animators, both in China and overseas.

But this golden age didn’t last. Nearly 60 years after the release of Havoc in Heaven, the Chinese animation industry is now struggling to generate revenues at home while trying to expand its presence in the global marketplace. To understand the current challenges facing Chinese animators, it is critical to recognize the history of how a once-prosperous industry fell behind its American, European, and Japanese counterparts and strived to regain its footing with radical adjustments.

The Wan brothers: Purveyors of early animation

To talk about the beginnings of Chinese animation is to talk about the life stories of the Wan brothers — Chaochen 超塵, Dihuan 滌寰, Guchan 古蟾, and Laiming 籁鸣. Growing up in a family with no artistic background — their father was a businessman in Nanjing and their mother was a stay-at-home mother — the four brothers were mad about painting and shadow puppetry when they were boys, with American cartoon series like Popeye the Sailor Man and Betty Boop being the backdrop of their childhood.

Although Wan Laiming, the oldest of all, had to drop out of school at the age of 17 due to financial hardship in his family, his three younger brothers attended art school and were determined to work in the field of arts. After several years apart, during which Wan Laiming went down the self-taught route while taking up a teaching job to make ends meet, the four brothers reunited in 1919 and embarked on an eight-year mission trying to figure out the basics of animation.

Soon, their ambitious yet risky endeavor paid off, and the brothers created — after much trial and error — the first Chinese animated short, a minute-long advertisement for a typewriter called the Shuzhendong Chinese Typewriter 舒振东华文打字机. By 1926, the brothers’ work had attracted the attention of the Great Wall Film Company, which invited them to create their next project, Uproar in the Studio 大闹画室.

Unfortunately, this short has been lost forever to history, but it helped boost the Wan brothers’ reputation at the time. In the years that ensued, the team cemented their status as pioneers of Chinese animation by continuously putting out awe-inspiring work, including Compatriots, Wake Up 同胞速醒, a patriotic, anti-imperialist short inspired by the Mukden Incident in 1931, which marked the first chapter in the Japanese invasion of China, and The Camel’s Dance 骆驼献舞, a 1935 short believed to be the first Chinese cartoon with sound.

In 1939, Wang Laiming and Wan Guchan caught a screening of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, the first feature-length animated film in movie history. Fascinated by its sound design and the details in its depictions of characters, the duo wanted to create something on par with the American game-changer. Working in Shanghai’s French Concession — a territory under French rule until it was relinquished back to the city in 1946 — the siblings set their sights on an episode from the 16th-century Chinese literature classic Journey to the West 西游记, naming their project Princess Iron Fan 铁扇公主.

And despite technical difficulties and an unsteady stream of funds from investors, Princess Iron Fan finally arrived in 1941, and it instantly charmed audiences with its unique drawing style and opera-tinged soundtrack. Adding to its commercial success at home, in 1942, the movie later made its way to Japan, where it was recognized as an enormous achievement of wartime filmmaking. It even made an impact on a then-teenage Osamu Tezuka, who later put his own spin on Journey to the West and produced the comic My Monkey King in 1952.

The golden age

With the enthusiastic reception of Princess Iron Fan, the Wan brothers felt confident enough to further their artistic ambition, and that’s when they started planning what would become their masterpiece, Havoc in Heaven. For six months, the siblings worked together on the movie, until higher-ups at Xinhua Film Company, where they were hired, came to the conclusion that selling film equipment was a more profitable business than producing actual films.

Devastated by the studio’s decision to suspend the movie’s production, Wan Laiming moved to Hong Kong to pursue his animation career. But due to a lack of funding, he had no choice but to put his love for animation aside and work as a set designer to earn a living.

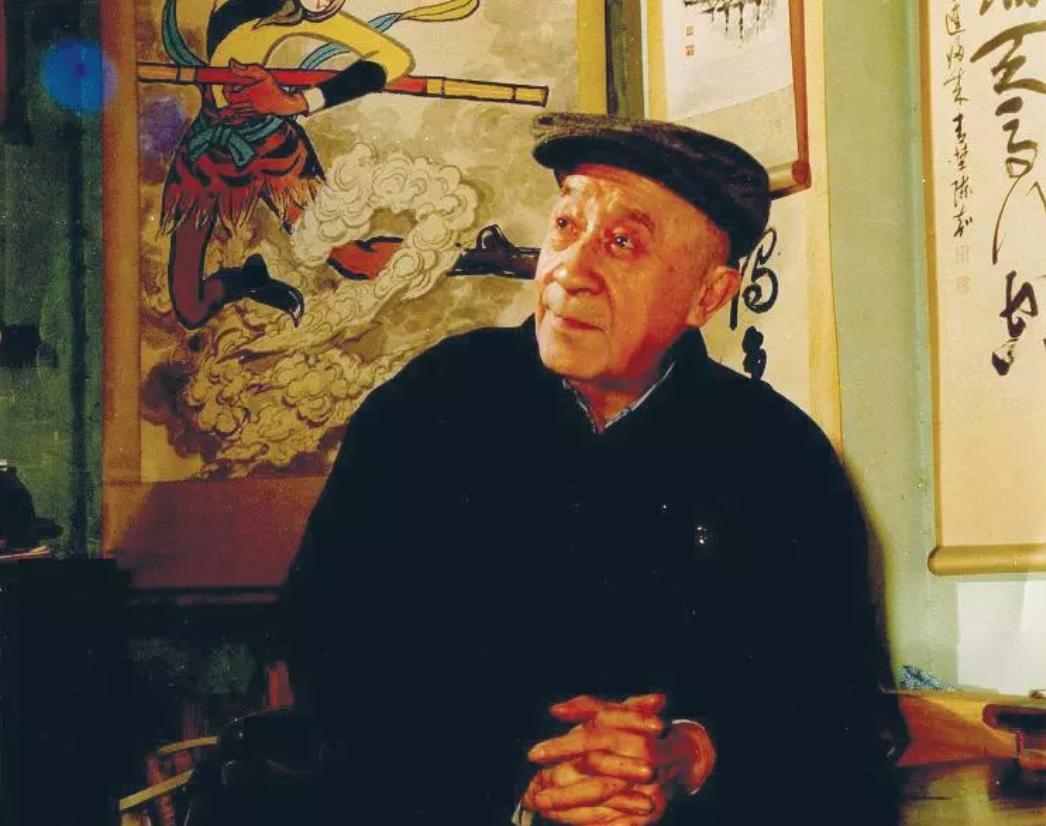

Things started to look brighter in 1951, when Wan Laiming returned to Shanghai. Around the same time, a group of Chinese animators founded the Shanghai Animation Film Studio. Naturally, the Wan brothers came together again and tapped into their years of creativity and experience to produce a series of shorts for the studio. Impressed by their work, the studio granted Wan Laiming permission to revive an old dream of his: Havoc in Heaven.

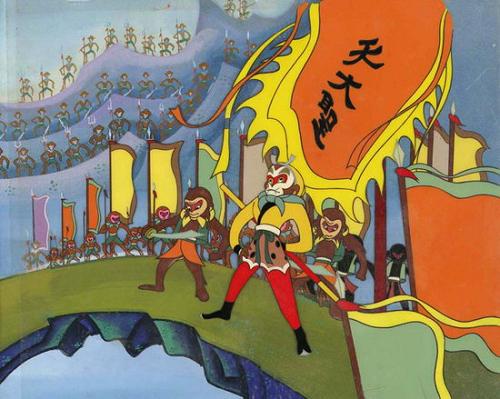

And the rest is history: Freed from the commercial pressure to compete with foreign imports, and aided by a 1959 governmental directive promoting the nation’s own graphic movie culture, the Wan brothers spent a total of five years designing and supervising the project’s 70,000 color drawings, which in the end came in the form of a two-part feature-length fantasy featuring the mischievous Sun Wukong. With its stunning visuals and beautiful music inspired by Peking Opera, Havoc in Heaven received numerous awards, as well as widespread domestic and international recognition.

There was a list of things that played into the success of Havoc in Heaven, including “its own properties of merits, such as amazing visualization and fictionalization of cultural contents,” according to Zhonghao Chen, a lecturer at XJTLU and a prolific artist. However, he added, “The curiosity phenomenon certainly played its part in terms of its positive Western reception. On top of that, the influence behind all the geo- and cultural-political puzzles at its time of viewing certainly aided the scenario.”

Chen is part of XJTLU’s new Academy of Film and Creative Technology, which launched May 22, with a remit to partner with media and creative industries to train students and professionals to become leaders in these industries.

For Dr. Hui Miao, an assistant professor in film studies in the Department of Media and Communication at XJTLU, Havoc in Heaven is her favorite animated film of all time because of its “engaging storytelling” and “craftsmanship.”

“Watching the film, especially now, is a process of appreciation of the work and passion of the dedicated team, who also had fun creating this masterpiece when the animation industry was new and fresh,” Dr. Miao said.

For Chinese animators in the 1960s and 1970s, the success of Havoc in Heaven opened a new world of possibilities, including, above all, the possibility of securing funds for animated movies that took years to make. Meanwhile, Chinese animation ballooned further into the mainstream thanks to a steady stream of critically acclaimed shorts and features — namely, 1960’s Where Is Mama? 小蝌蚪找妈妈 and 1988’s Feeling From Mountain and Water 山水清, an ink-wash animated film crafted by Te Wei.

“It is a representational assemblage of many essential cultural elements and their expanded applications,” said Chen. “The continuous exploration of ink medium is wonderfully contemplated. It serves not only as illustrative methodologies of narrative, but also the acknowledgement of its own materiality and culturality. For example, highly abstracted landscape painting applied as a moving image in the animation is such a genius idea, which carries not only strong aesthetics but also an abundance of philosophical search.”

Outsourced work is a double-edged sword

As China’s economic reform reached its height, the 1990s and early 2000s gave way to a relatively open television and film market, where Japanese and American animation powerhouses found a receptive audience among Chinese moviegoers. And as government-backed funding dried up and investors flocked to more profitable businesses, animation outsourcing started to take off in China, where cartoon factories sprung up, churning out frames for TV series and movies owned by foreign clients from Japan and the U.S.

Over the years, despite its financial gains, Chinese animators’ embrace of commissioned orders has attracted its fair share of criticism, with prominent detractors arguing that the business model has taken its toll on the Chinese animation industry, making domestic companies less motivated to pursue original content and ideas.

However, according to Dr. Marco Pellitteri, a media sociologist and an associate professor in the Department of Media and Communication at XJTLU, the phenomenon is not wholly negative. “Outsourcing has had a deep impact on Chinese animators and animation producers, and I believe it is a generally good impact, in terms of consolidating technical skills, organic and orderly production pipelines, and the ability to plan, produce, and launch serial products as well as feature movies, together with a ‘media mix’ strategy that has proven to be highly profitable, although mainly or only in the domestic context,” he said.

Dr. Pellitteri pointed out that China isn’t the only country that plays a part in this “international dynamic.” South Korea, for example, was also a destination for outsourced assignments from Japan back in the 1970s, and the trend helped local animators hone their skills and create acclaimed domestic feature-length films in the years to come. “Coming back to China, what Chinese animation as a system has not been able to apply properly yet is in the creation of internationally fashionable, appealing narratives. The responsibilities, however, do not just lie upon the shoulders of animation studios,” Dr. Pellitteri added. “The reasons are more faceted than that.”

Going global is no easy feat

The year 2018 was a turning point for Chinese animation. After five years in the making, Ne Zha 哪吒, an epic animated fantasy film based on a well-known ancient folk legend, smashed box office records in the summer, raking in over $742 million to date and becoming the second-highest-grossing film in the history of Chinese cinema. Outside of movie theaters, Chinese audiences’ enthusiasm for domestic animated series also went through the roof following the launch on major video-streaming platforms of several popular shows such as Mo Dao Zu Shi 魔道祖师.

“Ne Zha has a strong story, comedy, and great visuals in terms of kinetic movements and bold colors,” said Kelvin Ke, a filmmaker and an assistant professor in communication studies at the Department of Media and Communication at XJTLU. “But more importantly, it has a strong central character, which I find appealing in a movie. Specifically, I think the movie is a great example of a movie that focuses on the importance of growth, maturity, and self-determination.”

The movie’s unusual characterization of Ne Zha, a well-known fictional character in Chinese literature, is also what captivated Hui Miao the most when she watched it. “Instead of aligning his personality with the tradition, the film characterized him as a social outcast. He was not a mainstream character and constantly, in his own ways, tried to find out where he fit in in this world,” Dr. Miao commented. “This resonates with the modern and globalized living condition, seemingly sufficient with everything we want, but everything comes with overwhelming loneliness and alienation.”

This glimmer of hope, however, was short-lived. Building on the world of blockbuster Ne Zha, Jiang Ziya 姜子牙, a Chinese computer-animated fantasy adventure film released in 2020, was met with an outpouring of disappointment from critics and average moviegoers, who took particular issue with its awkward action sequences and confusing character development. Meanwhile, Kung Fu Mulan, a Chinese-produced animated Mulan movie, was hit with a wave of brutal reviews when it came out in October last year. The reception was so negative that it got pulled from theaters just three days after its release.

Asked about his thoughts on recent blockbusters like Ne Zha, Dr. Pellitteri stressed that they racked up monster figures and rave reviews almost exclusively in China. Reading reviews from foreign critics, Dr. Pellitteri said that he got the feeling that “they were kind and polite out of respect for the great effort of the Chinese production.” However, “the rhetorics of their wording” left him with “a sense of an implicit technical and critical disappointment.”

“While Ne Zha is, technically and narratively, certainly not a perfect movie, the problem is, rather, in the current overall perception about Chinese animation around the globe: Since the performance and quality of Chinese animations in the last decades are considered of mild or unsatisfactory level if compared with Japanese or American productions, Ne Zha, unfortunately, was received with prejudice and a certain superficiality worldwide, and was also penalized by the sudden outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic, which generated, alas, a discriminatory attitude about it,” Dr. Pellitteri added.

To break into the global market, Dr. Pellitteri suggests that Chinese animators should improve in both technical and storytelling aspects. He also noted that Chinese scriptwriters and producers seem inclined to “fill a certain animated product with a pre-set list of things” that appeal to Chinese moviegoers — such as “Confucian values, rich visual decorations, and elements of history and folklore” — but they are likely to be given the cold shoulder by international audiences.

“It has been widely studied how the cultural influence of anime and manga has produced, to a degree, some amount of ‘soft power’ for Japan as a country. Therefore, if Chinese animation production companies think that their films and series should have a function to boost the sympathies for the country among foreign viewers, I would suggest that producers and stakeholders look at Japan’s case history,” Dr. Pellitteri said. “The Japanese government’s attempt to commodify soft power through the fictional characters and stories of anime has basically failed, and it has also met with the vigorous objections of animation producers and creators, who want to remain free to decide what goes into a story and what characters should do, say, and think in that story, without the need to underline Japan’s grandeur.”

Looking forward, Ke said that he could “only see great things to come for Chinese animation.” But he was also keenly aware of the pressures placed on Chinese animators to create blockbusters, which he said would “make it harder for them to try something different.”

Jiayun (Jenny) Feng is the Society and Culture Editor at The China Project. Born and raised in Shanghai, she is a bilingual journalist committed to reporting on China-related issues with a global perspective. Read more

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Performance cookies are key in allowing web site screens and content to load quickly on all types of devices.

| Cookie | Description |

|---|---|

| _gat | This cookies is installed by Google Universal Analytics to throttle the request rate to limit the colllection of data on high traffic sites. |

| YSC | This cookies is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos. |

Preference cookies are used to store user preferences to provide them with content that is customized accordingly. These cookies also allow for the viewing of embedded content, such as videos.

| Cookie | Description |

|---|---|

| bcookie | This cookie is set by linkedIn. The purpose of the cookie is to enable LinkedIn functionalities on the page. |

| lang | This cookie is used to store the language preferences of a user to serve up content in that stored language the next time user visit the website. |

| lidc | This cookie is set by LinkedIn and used for routing. |

| PugT | This cookie is set by pubmatic.com. The purpose of the cookie is to check when the cookies were last updated on the browser in order to limit the number of calls to the server-side cookie store. |

Analytics cookies help us understand how our visitors interact with the website. It helps us understand the number of visitors, where the visitors are coming from, and the pages they navigate. The cookies collect this data and report it anonymously.

| Cookie | Description |

|---|---|

| __gads | This cookie is set by Google and stored under the name dounleclick.com. This cookie is used to track how many times users see a particular advert which helps in measuring the success of the campaign and calculate the revenue generated by the campaign. These cookies can only be read from the domain that it is set on so it will not track any data while browsing through another sites. |

| _ga | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, campaign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gid | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the wbsite is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages viisted in an anonymous form. |

| _omappvp | The cookie is set to identify new vs returning users. The cookie is used in conjunction with _omappvs cookie to determine whether a user is new or returning. |

| _omappvs | The cookie is used to in conjunction with the _omappvp cookies. If the cookies are set, the user is a returning user. If neither of the cookies are set, the user is a new user. |

| GPS | This cookie is set by Youtube and registers a unique ID for tracking users based on their geographical location |

Advertisement cookies help us provide our visitors with the most relevant ads and marketing campaigns.

| Cookie | Description |

|---|---|

| __qca | This cookie is associated with Quantcast and is used for collecting anonymized data to analyze log data from different websites to create reports that enables the website owners and advertisers provide ads for the appropriate audience segments. |

| _fbp | This cookie is set by Facebook to deliver advertisement when they are on Facebook or a digital platform powered by Facebook advertising after visiting this website. |

| everest_g_v2 | The cookie is set under eversttech.net domain. The purpose of the cookie is to map clicks to other events on the client's website. |

| fr | The cookie is set by Facebook to show relevant advertisments to the users and measure and improve the advertisements. The cookie also tracks the behavior of the user across the web on sites that have Facebook pixel or Facebook social plugin. |

| IDE | Used by Google DoubleClick and stores information about how the user uses the website and any other advertisement before visiting the website. This is used to present users with ads that are relevant to them according to the user profile. |

| mc | This cookie is associated with Quantserve to track anonymously how a user interact with the website. |

| personalization_id | This cookie is set by twitter.com. It is used integrate the sharing features of this social media. It also stores information about how the user uses the website for tracking and targeting. |

| PUBMDCID | This cookie is set by pubmatic.com. The cookie stores an ID that is used to display ads on the users' browser. |

| TDCPM | The cookie is set by CloudFare service to store a unique ID to identify a returning users device which then is used for targeted advertising. |

| TDID | The cookie is set by CloudFare service to store a unique ID to identify a returning users device which then is used for targeted advertising. |

| test_cookie | This cookie is set by doubleclick.net. The purpose of the cookie is to determine if the users' browser supports cookies. |

| uid | This cookie is used to measure the number and behavior of the visitors to the website anonymously. The data includes the number of visits, average duration of the visit on the website, pages visited, etc. for the purpose of better understanding user preferences for targeted advertisments. |

| uuid | To optimize ad relevance by collecting visitor data from multiple websites such as what pages have been loaded. |

| uuidc | This cookie is used to stores information about how the user uses the website such as what pages have been loaded and any other advertisement before visiting the website. This data is used to provide users with relevant ads. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | This cookie is set by Youtube. Used to track the information of the embedded YouTube videos on a website. |