Zhang Hong lost his vision at age 21. Then he climbed Mt. Everest

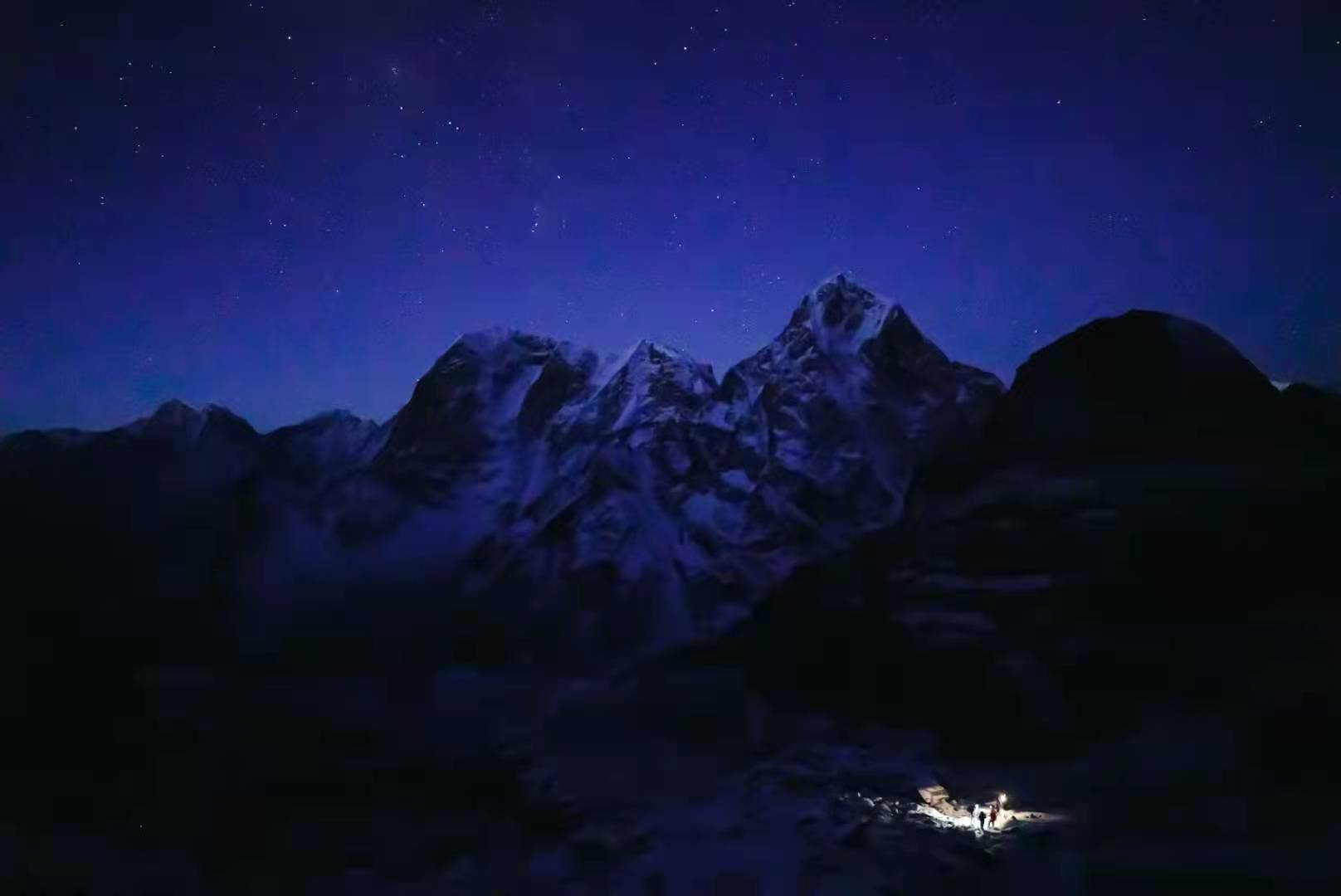

On May 24, Zhang Hong arrived at the summit of Mount Everest, becoming the first blind Chinese mountaineer to make the 8,849-meter climb.

Jiahui Yue contributed to research and interview.

On the rock face of Mount Everest, the 46-year-old Chinese mountaineer Zhāng Hóng 张洪 etched his name alongside that of Erik Weihenmayer and Andy Holzer. Out of more than 4,000 climbers who have summited the world’s tallest peak, these three men share one trait: they are blind.

After multiple delays due to bad weather, COVID-19, and government restrictions, Zhang completed the 8,849-meter climb on May 24. Following in the footsteps of Weihenmayer and Holzer — who climbed Everest in 2001 and 2017, respectively — Zhang is the first blind person from Asia to complete this achievement.

Born in Chongqing in southwest China, Zhang lost his sight at the age of 21. Like his father and uncle before him, Zhang suffered from glaucoma, one of the leading worldwide causes of blindness. Within three months of his diagnosis, Zhang lost all vision. “I was in an abyss of despair and couldn’t accept this cruel new reality,” he said. Zhang missed China’s college entrance exam and worked as a migrant worker before training as a blind masseur at a Tibetan hospital. Even before losing his sight, Zhang admitted to facing isolation and ostracization from his family, and upon his diagnosis, battled suicidal thoughts.

Zhang’s interest in climbing began almost by happenstance. While working at the hospital in Lhasa in 2015, he crossed paths with the famous Tibetan mountaineer Luò Zé 洛则. Luo is part of an elite group of climbers who have successfully climbed all 14 of the world’s 8,000-plus-meter peaks.

“I had no concept of climbing before I met [Luo],” said Zhang. “I admired him as a hero, but I didn’t think mountain climbing could be for me. Suddenly, though, I asked him: ‘Do you know if there have been any blind people to climb Mount Everest?’”

It was through this chance encounter that Luo introduced Zhang to Weihenmayer’s story.

“Learning about Erik’s story gave me the idea that blind people can do a lot of things,” said Zhang. He began working with Qiáng Zǐ 强子, a mountain guide who helped teach him how to climb.

Before fully committing to Everest, Zhang tackled a number of peaks in China, including Snow Mountain in Yunnan province and Mount Muztagh Ata in Xinjiang. In 2019, after successfully climbing peaks 7,546 meters above sea level, Zhang officially decided that Everest could be possible.

But first, he had to secure the funds. Zhang spoke with many mountaineering experts to better understand the financial barriers associated with climbing Mount Everest. During these conversations, he met with the owner of a climbing company who put him in touch with the Beijing-based film director Fàn Lìxīn 範立欣, renowned internationally for his award-winning documentary Last Train Home.

“At the beginning of last year, [Fan and I] met in Chengdu,” Zhang said. “He did a lot of thinking and determined that [my] story could be very meaningful.” From then on, Fan and his film crew followed Zhang throughout his entire Everest journey.

Training was both a physical and mental challenge. Initially, Zhang climbed stairs with weighted bags at the hospital where he worked. He would walk the stairs from the second floor to the 11th floor every day. He kept adding weights in five-kilogram increments, topping out at about 35 kilograms, and climbed thousands of stairs. Zhang described this type of training as monotonous but essential for building up stamina. He supplemented this strength training with nightly sessions at the gym. Eventually, he began doing more technical training, such as rock climbing and simulating walking on snow or icy terrain.

“Fitness is something I can put under my control,” Zhang said. “But mastering something like climbing took me a long time. Maybe several times more than sighted people.”

Zhang said that ice climbing in particular was the hardest challenge for him.

“At the beginning of this part of the training, it took me a long time to understand and get familiar with [ice climbing]. I had to first just let my mind get used to it and to understand what ice climbing is,” he said. “At first, I could not grasp the essentials, such as ice walls, and how to step up. I didn’t know how to kick the ice with my feet and to use the ice axe to support my weight.”

Learning how to use the equipment was another challenge. “I was a little skeptical about the protection because I had never been exposed to it before. I wasn’t trusting enough,” he said. Zhang also had to have deep trust in his guides. In addition to Qiang Zi, he was accompanied by two alpine photographers as part of Fan’s crew. Three Sherpa guides — Lhakpa Sherpa, Dawa Wongchu Sherpa, and Samden Bhote — were also by Zhang’s side.

Nepal reopened Mount Everest in April after it had been shut down for the COVID-19 pandemic. At that point, all of the other pieces were in place for Zhang, including the necessary funds and registration from the Nepalese government.

On April 3, Zhang and his team began their trek to the Everest Base Camp. He met many other mountaineers from all over the world. The fact that they spoke different languages didn’t affect their communication — though Zhang admitted later that he set a goal for himself to learn English by the end of his trip. On the third day, Zhang met up with a climber named Paul, who had traveled from Greece. “We met because of this same hobby, and it’s like we’ve been friends for years. He made the deepest impression upon me,” Zhang said. The two became good partners as they trekked to the base camp.

“The biggest lesson he gave me was the power of optimism. Although we could not communicate very smoothly, every time we would give a pat on the shoulder or a hug, that would reveal the kind of unconditional encouragement that is so deeply appreciated.” Zhang taught Paul tai chi, while Paul taught Zhang Greek dance. Eventually, the two parted ways.

About a week in, Zhang’s group reached Nanzaki Bazaar, about 3,400 meters above sea level and a critical height to acclimate to the elevation. Helicopters flying to Everest base camp to deliver supplies could be heard overhead. The group stayed at the same inn where Weihenmayer had stayed when he came to trek 20 years earlier.

By April 11, Zhang and the group had completed the first stage of their journey and reached Everest base camp, about 5,364 meters above sea level.

A week and a half later, the team was acclimated and ready to continue. But on the day they were supposed to depart, strong winds and bad weather conditions swept in. Hurricanes in the Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal had thrown off the whole climbing cycle.

“I was very anxious,” Zhang said. “On one day the weather forecast for the next would look positive and we would be ready to go. But then the situation would quickly change as the weather worsened. It was like this, anxiously waiting each day.”

During this time, rumors began circulating that, despite all precautions, cases of COVID-19 had broken out. The team invited doctors from Kathmandu on chartered helicopters to do a final PCR test to ensure everyone was COVID-free. The entire group stayed up on the final night for the last test result to come back.

By May 20 — more than a month after reaching base camp — a new window of good weather finally opened, and a few days later, the group was off for their final ascent.

For the most part, Zhang stayed on Qiang Zi’s arm as they navigated the most dangerous areas — the so-called “death zones” made of ice walls and icefalls. Two Sherpas were mainly responsible for carrying supplies and oxygen, while one Sherpa was in front of Zhang and Qiang Zi as a guide. Qiang Zi would give vocal directions to Zhang, using clock directions to describe where Zhang should make his next steps.

“Each step of the march was difficult,” Zhang said. The group moved slower than others, and the guides became worried about their oxygen levels.

“[Qiang Zi] felt that if we were going at such a slow pace to the summit, then we might face a shortage of oxygen and actually not make the final ascent, compromising everyone’s safety,” Zhang said. “At this time, he made a decision. He decided to give me his oxygen to ensure my final ascent. Qiang Zi, along with his Sherpa, chose to withdraw.”

At this point, Zhang felt very scared. Fan Lixin’s photographers and videographers had already withdrawn from the climb, and Qiang Zi was the final Mandarin speaker accompanying him.

“I said to Qiang Zi, ‘I don’t want to go up if you do not go up,’” Zhang said. “But he told me, ‘Zhang Hong, if you do not continue, this is perhaps the last opportunity you will have.’” With that encouragement, Zhang pressed on. “He didn’t have to explain more,” Zhang said. “With a gentle push, he hurried me on.” Then again, Zhang noted, “at that high altitude, there is no time for arguments.”

The final day of the ascent was the most challenging. Zhang and his three Sherpa guides were not able to fluently communicate with one another. Because the winds were so strong, there was no way for the group to stop and rest. But at the very least, the guides were able to instruct “up” or “down” and convey how many centimeters to move.

Finally, on May 24 at 9:30 a.m., Zhang arrived at the summit, becoming the first blind Chinese mountaineer to climb Mount Everest — and on his first attempt, too.

Zhang hopes that his story may inspire others, as Weihenmayer inspired him.

“There are now 450,000 people in China who go blind in the middle of their lives every year for various reasons. Like me, many of them will have a hard time adjusting to this new life,” Zhang said. “I hope that my story and my experience can influence more blind people and people with disabilities, so that they can come out, do what they want to do, open up society, and not be limited by many things.” As a part of this endeavor, Zhang also hopes to be a guide and enable other visually impaired climbers in the future.

“Although we cannot see this wonderful and colorful world, we cannot see any difficulties or obstacles either,” he said.

Zhang is now preparing to tackle the rest of the Seven Summits, the highest peaks in all the world’s continents. His journey has only begun.