Bishan, revisited: Lessons from a ‘rural utopia’ in central China

The Bishan Project was a radical — and short-lived — rural experiment that left a mark on Chinese governance and art. Five years after its closure, we consider whether it was ahead of its time, or if it ever had a chance.

I woke up to the sound of hens, geese, and pigs rummaging outside the window of my white-chalked and black-eaved cottage deep in the Anhui countryside. It was nestled beneath lush mountains, together with scores of other walled villas among green fields inhabited by water buffalos and laboring peasants.

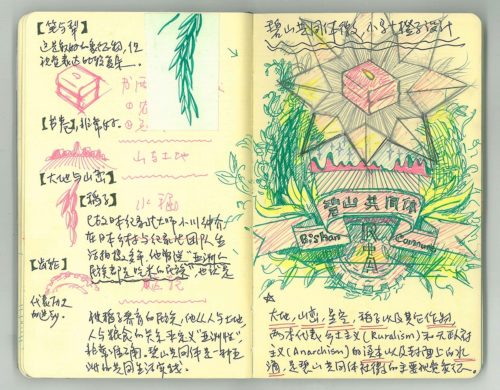

This was in 2015, when I visited the “Bishan Project,” set up in 2011 by Chinese artists with an anarchist and rural reconstructionist vision, hailed by international observers like the Guardian and New York Times as a new way for reviving the Chinese countryside.

Just a year later, it was closed down and taken over by the government.

But Bishan would leave a legacy on governance, rural revitalization, and the Chinese art scene. Five years on, I spoke with Ōu Níng 欧宁 says — one of the artists who founded the Bishan Project — and Mai Corlin, who has recently published a book about the project, The Bishan Commune and the Practice of Socially Engaged Art in Rural China.

“If your influence outweighs the power of the government, it will also pose a challenge to it,” Ou Ning tells me. He is a veteran artist who cut his teeth in the Beijing art scene in the 1980s and ’90s as a writer, filmmaker, curator, and publisher of several magazines. In Bishan, he learned firsthand how far a bottom-up approach in the countryside could be taken.

A “radical” idea

Bishan Commune was supposed to create a new direction for development, together with locals. For a country in which city life had been idealized, this was a radical idea. Like many other Chinese artists and academics at the time, Ou Ning recognized the problems in the Chinese countryside, which had long been neglected. Depopulation, expropriation of farmland, and the loss of village culture were just some of the consequences of rapid urbanization.

“I want to establish my own ideal society, to provide an alternative to our current society. One that’s not in opposition, but co-exists,” he told the Chinese magazine 0086 in 2010, about his vision for the Bishan experiment.

The “ideal society” that Ou Ning envisioned was a socially engaged art project that would give the locals, most of them farmers, a renewed sense of pride in their craftsmanship and old techniques — before they were lost for good, in some cases. “Begin with what is already there,” Ou Ning said before setting up the commune. “Begin with what the peasants already know, don’t impose a new system of knowledge on them, but begin with the knowledge they already have and slowly provide them with new things.” Through this mantra, Ou Ning echoed intellectuals like the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin and the Chinese rural reconstructionist James Yen.

“It’s a utopia, an idea of co-living,” he said.

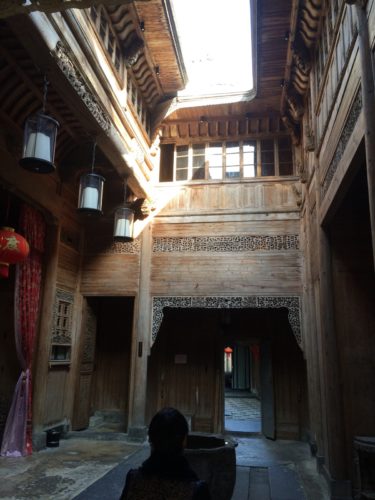

Bishan is one of many villages in the Jiangnan region, a geographic region south of the Yangtze River (“jiang” means river, while “nan” means south). For many years it lay humble, nondescript, and somewhat insignificant compared to the nearby Yellow Mountains and other UNESCO Heritage Sites. But the town has been gifted with architectural heritage, such as an ancient pagoda, temples, ancestral halls, and dozens of villas with enclosed courtyards that open up to the skies all year round, through a roof edifice known as the “heavenly well” (天井 tiānjǐng).

Ou Ning set up the Bishan Project in 2011 with fellow artist and curator Zuǒ Jìng 左靖. Here, they founded the festival “Harvestival,” intended to be one of the official holidays of the commune.

The operation of the commune was centered around art projects, whereby artists aimed to bring awareness and a sense of value back to the villagers. This included rebranding village goods, like foodstuffs and clothes, and selling them online and for visitors in the village.

Another major part of the commune was to create spaces that could serve as gathering points for villagers, artists, and visitors. The Nanjing-based Librairie Avantgarde opened a branch in Bishan along with the boutique guesthouse Pigs Inn and the combined art gallery and activity center The School of Tillers.

The construction and inflow of visitors made some villagers and local officials hope for a tourism boom. These hopes were not in immediate opposition to the direction that the artists were taking — their vision was, after all, to make a new kind of development that included and valued the skills of locals. But some locals mistakenly imagined tourism development to be on the same scale as in neighboring UNESCO “ancient towns” of Hóngcūn 宏村 and Xīdì 西递.

Those areas had been massively redeveloped, with newly built infrastructure, ticket booths, fast food restaurants, and souvenir stalls. In contrast, many of Bishan’s old Qing dynasty houses still stood as they did when they were constructed after the Taiping Rebellion. Restoration efforts would most likely damage the architecture and turn the villagers away from their family trades to those of the tourism industry. Overall, this might be good for development, but not for craft traditions and other intangible culture.

This was the central conflict of the Bishan Project: striking a balance between rural revival and economic development for the local population.

Tensions in Utopia

Ou Ning had made it clear early on that Bishan was to be in coexistence with the surrounding society. His efforts had, from day one, included local officials at the village and county levels, together with constant dialogue with villagers. The bottom-up approach, with Ou Ning trying to find common ground between all these actors, was initially praised, but this type of “radical consensus democracy” soon ran into limitations.

At the second Harvestival in 2012, festivities were not allowed to go on as usual. This was the first time that the project encountered trouble. In hindsight, there were several contributing factors, though the exact reasons were never given to Ou Ning. The festival was scheduled for the same week as China’s leadership handover, when Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 assumed office. Another reason might have been that one of the exhibitions was by the American China scholar Orville Schell, who conducted research on the student protest movement in 1989.

In the years that followed, the question of tourism and redistribution of money became a central issue. Some villagers thought of the artists as big outside bosses (外地来的老板 wàidì lái de lǎobǎn). They had seen wealthy investors lay millions in other villages, following the usual template for tourist sites. So why was the same not happening in Bishan?

The dispute crescendoed in 2014, when the Harvard Ph.D. student Zhōu Yùn 周韵 wrote a blog post after visiting the Bishan Commune titled, “Whose Countryside, Whose Community? Taste, Distinction and the Bishan Project.” Zhou criticized Ou Ning and the Bishan Project for disconnecting the villagers from the decision-making process.

Political winds were also changing. In 2016, the central government issued a statement to close the Bishan commune, and all electricity was abruptly shut off. Ou Ning himself had not been in contact with local officials, but heard from people in the village that he should leave. “He was informed that there was a meeting about the Bishan commune with the villagers,” the researcher Mai Corlin says. “They were told that the commune was not ‘politically correct,’ and that they needed to ‘strengthen party leadership.’” Just like that, the artists were out, and the party assumed control.

Bishan’s legacy

In many ways, Ou Ning was actually ahead of his time. The prominent government campaigns of “poverty alleviation” and “rural revitalization” have put the countryside in the spotlight. But recent campaigns have all been led by the Party, meaning successes should be attributed to the Party.

“Ou Ning definitely crossed the line by proposing the idea of radical consensus democracy in an evidently non-democratic system,” Corlin says.

For local governments, Bishan as a case study presented several lessons. First, there was no question that development should only happen under Party auspices. Second, involving locals — preserving the skills of villagers, for instance — should be seen as an essential part of rural revitalization. As Corlin explains, “Ou Ning and Zuo Jing engaged the villagers by proposing other ways for their village to develop, by treasuring the handicraft traditions of the area and by urging villagers to do the same.”

In recent years, tourism has moved away from theme-park building — prominent during heady development days under President Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛 — and toward “authenticity.” Local officials are using lessons from Bishan to pursue cultural revitalization. Some artists from Bishan have been invited to advise local governments on how to bring the Bishan model elsewhere.

For Chinese artists and intellectuals, Bishan demarcated how far socially-engaged art could be taken in China. The prominent painter Qiū Zhìjié 邱志杰 included Bishan in his work “Map of the Theater of the World” (a.k.a., “Mappa Mundi”), which was exhibited at the Guggenheim.

“Practically speaking, when doing things in China, we cannot challenge the authority of the government,” Ou Ning says when I ask what his greatest lesson was from the Bishan Project. For him, the important bigger question, though, is whether or not we are seeing a “local turn” back to the countryside today, which was the core focus of the Bishan Project from the start. Ou Ning believes that this will be a future tendency both in and outside of China. “Rural areas will be the focus of construction in the post-epidemic era. I think there will be a ‘local turn’ all over the world.”

Corlin went back to Bishan in 2019 and met with many of the villagers she had interviewed during her research. “It was still politically sensitive to talk about when I went there, but most of the villagers were happy with the development that Bishan had undergone. Some said that they recall the time when Ou Ning was there as very nice and refreshing.”

They had accommodated the arrival of the artists and taken part in the art activities, only to see the project shut down. But then roads were developed, so all in all, looking back, many view the experiment as having created positive changes. Still, they are aware that Bishan has gained political connotations, and that the attention of the central government means something bigger is going on — much to their chagrin. Villagers want development, not attention, either negative or positive.

Lately, it looks like the rural revivalist vision has swung back to Bishan once again. In 2021, one of the major national policies being pursued is rural revitalization (国家乡村振兴 guójiā xiāngcūn zhènxīng), with the “ideal village” being one that is in harmony with nature, traditional customs, and culture.

“I visited Bishan in May,” Ou Ning says. “The paved stone road was being dismantled in the village, and the water pipes were laid and covered with stone slabs again.”

There may yet be a second revival in rural Anhui. It might even be built using the old blueprints of Bishan.