The CCP was founded in 1921 as an agrarian party dedicated to redressing inequalities between the city and the countryside. On its centenary, Chang Che reflects on how the Party has evolved, and how its relationship with the people has changed.

At dusk on June 28, in one of Shanghai’s upscale shopping districts, a fountain show erupted from Taiping Lake, with beams of red and yellow light projected onto a watery curtain. Onlookers gathered as images and slogans from China’s past flashed by, while “The East is Red,” a revolutionary anthem, blared from an unknown source.

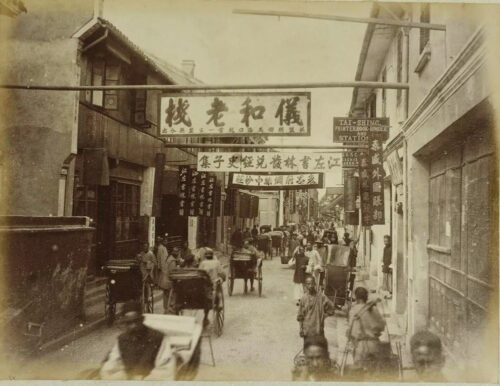

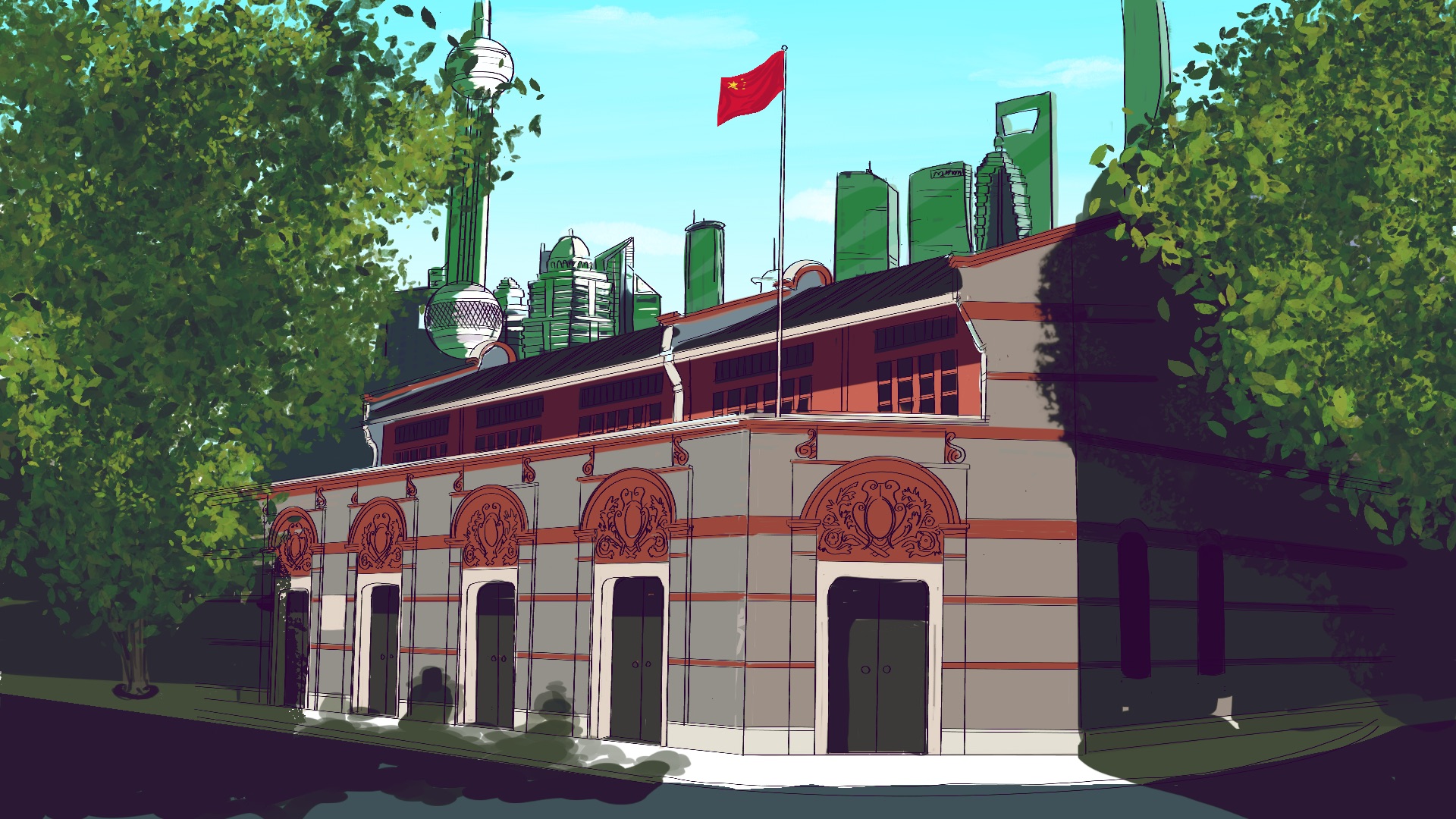

It was here 100 years ago, in a traditional brick-walled house called a shikumen, where a dozen young men first solidified their Marxist convictions into a group they called the “Communist Party of China” (中国共产党 zhōngguó gòngchǎndǎng). None of them would recognize the area today.

Shanghai, the birthplace of the Party — or “the base of socialist construction,” as one official put it — is now home to the highest concentration of coffee shops and malls in the world. The historic shikumen where China’s first communists met is now a memorial hall in the heart of Xintiandi, a commercial playground for China’s growing middle class. Directly adjacent to this heritage site is a Starbucks and a Shake Shack.

On July 1, 1921, the dozen members of the soon-to-be Communist Party met here in secret. Fearing arrest, the group reconvened days later on a boat in a nearby lake. Six years later, on April 12, 1927, the fledgling party suffered a violent purge by the Nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí). The assault splintered the group, but one faction, led by a steely-eyed man from inland named Máo Zédōng 毛泽东, escaped the siege and embarked on a treacherous journey into the countryside. Ten years later, Mao would consolidate his forces and win a decisive war against the Nationalists, forcing them to flee to the nearby island of Taiwan. In 1949, at a ceremony in Tiananmen Square, the emergent leader declared that the country had “stood up,” ushering in a new chapter of the Chinese epic.

Shanghai residents couldn’t avoid this history even if they tried. In the past few months, the city itself became a classroom. There was something for everybody. Casual explorers could visit hundreds of newly refurbished “patriotic education bases,” including the memorial hall which reopened a few weeks ago. (This week, the hall was open only to those with “permission”). Visual learners could find a virtual tour of the exact same sites on the propaganda app “Study Xi, Strong Nation,” the official teaching platform for young officials. Audio buffs could download the new state-run podcast Tales of Huangpu River, sponsored by the Shanghai municipal government, about the early days of the Communist Party. In March, Hollywood releases were replaced in movie theaters by state sponsored “red movies” such as The Founding of the Party and Sparkling Red Star. East of the Huangpu River, bankers in the finance district found their office floors drenched in the bright red of centenary banners beamed out of 303-meter-tall tower screens. Out on the Bund, a couple looking up to the sky, in search of stars, found a massive drone exhibition featuring images from the Party’s past. In this history class of a city, the method of instruction was total immersion.

For Party officials, the centenary is an opportunity not just to review this history, but to polish the final copy. “The Party’s history is the most vivid and convincing textbook,” said Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 at a museum exhibit in February. It was a subtle admission: history, in China, is not the mottled sum of written accounts filtered through public deliberation. It is a textbook written by a single author — the Party. The museum, like the light show presentation, conjured a nonexistent halcyon past. Exhibitions featured paintings of the Shanghai conference, the victory of the Communists in the Civil War, the founding of the PRC, and the period of reform and opening. No references were made to the equally identity-forming episodes of famine, leadership failure, and violent protest suppression.

The Party’s selective memories form the basis of two ideas animating the centenary this year. The first is a logical extension of the moment’s sheer improbability. In the years after the Soviet Union collapsed, the prevailing view among most observers was that China would soon follow. When Arab dictatorships fell in 2011, those expectations grew. But the Party survived both crises. It seemed fair, back then, to chalk up those successes to a form of foul play: censorship, repression, and violence. Yet this year’s centenary comes just after a deadly pandemic in which China recovered much faster than its Western counterparts. This has lent moral credibility to a country that has traditionally steered clear of talk of universal values. As Xi has mentioned time and again, China’s pandemic response was proof that China’s political system was superior — not just practically, but morally — to liberal democracy. For the first time since the end of the Cold War, democracy was on the defense.

The second idea is the persistence of traditions. In a past riven by deep political and societal disruptions, the now-century-old Party seeks continuity and stability. “Don’t forget the original intention. Stick to the mission,” Xi has advised repeatedly. The Party has never fully let go of its Marxist scriptures: allegiance to the proletariat or, in the Party’s case, rural villagers. No surprise, then, that this lunar new year began with a major announcement on poverty eradication, in which Xi declared China to have “eradicated extreme poverty for the nearly 100 million rural people affected.” “The past 100 years,” preached Xinhua, has seen the Party “unswervingly fulfilling its original aspiration and founding mission.”

In his new book The End of the Village, the scholar Nick R. Smith reexamines the conditions of rural villagers the Party claims to represent. According to the People’s Daily, “the story of Xi Jinping and the villagers eradicating poverty is the story of the Communist Party.” But Smith, who has done fieldwork in villages across China and is now an assistant professor at Barnard College, told me that the CCP fundamentally approached rural development from an urban lens: “What urbanites think rural development should be and what a rural person should want.” For villagers, the Party’s anti-poverty initiatives can be a “debilitating transition,” he said. Villagers have their own way of life, but “all of a sudden, the Chinese government comes and says ‘No, we know better. We’re going to move you into this high-rise and separate you from everything you’ve known and all of your social networks.’” When I asked him what he thought of Xi’s speech touting the millions of rural people lifted from poverty, Smith didn’t mince words: “I would say go ask those people whether they’re happy or not.”

That the Party has alienated the people it purports to represent is symptomatic of the seismic shift that has occurred in the last four decades. At its founding in 1921, the CCP was a predominantly agrarian party dedicated to redressing inequalities between the city and the countryside. Today, those motives persist on paper, but surveys show that for most people, the prevailing motive for joining the Party is career advancement. One becomes a Communist, in other words, to get access to privilege, not to distribute it. In 2018, only 1 in 350 new Party members were migrant workers, despite that group accounting for roughly a third of China’s working-age population. In rural areas, small business owners are prioritized for party membership over farmers. “The Party is no longer a workers’ and peasants’ party,” says Richard McGregor, author of The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers. “It is a managers’ and businessmen’s party.”

At its 100th birthday, the Party is looking toward the future with unvarnished optimism: the “new era,” officials say, will be marked by China’s emergence as the world’s largest economy and a leading technological superpower. But much of this is premised on the skillful navigation through a flotilla of course-altering icebergs: they include a demographic crisis, flagging productivity, a stagnating economy, uncontrolled debt, deep-seated environmental issues, and political unrest in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. Moreover, the government’s current clampdown on its sprawling tech sector is unprecedented, its future impacts unpredictable.

To address these challenges, the Party promises prosperity, pride, and strength. For a while, that was enough. But like elsewhere in the world, the newly affluent in China are in search of more than money; often, they want recognition from their global peers. Thus, Chinese entrepreneurs now dream of making internationally renowned brands, Chinese youths are turning toward artistic modes of expression, and Chinese parents still pay a fortune to educate their children abroad. Middle-class priorities — from property to entrepreneurialism, to transparency, to accountability — are more closely aligned with that of the West than those of the Party. For now, “China’s nascent middle class tends to emphasize the status quo,” says Cheng Li, author of Middle Class Shanghai. “But this may be only a transitory phase.”

In Shanghai, where I live, the women wear business suits and the men frequent beauty salons. Nothing stays the same. The city is often seen as the place where the Party was born, but it is also where the country — its people, its culture, and its values — are maturing and evolving. Just as China’s history is far more complicated than its textbook, the view from below is far less certain than the view from above.