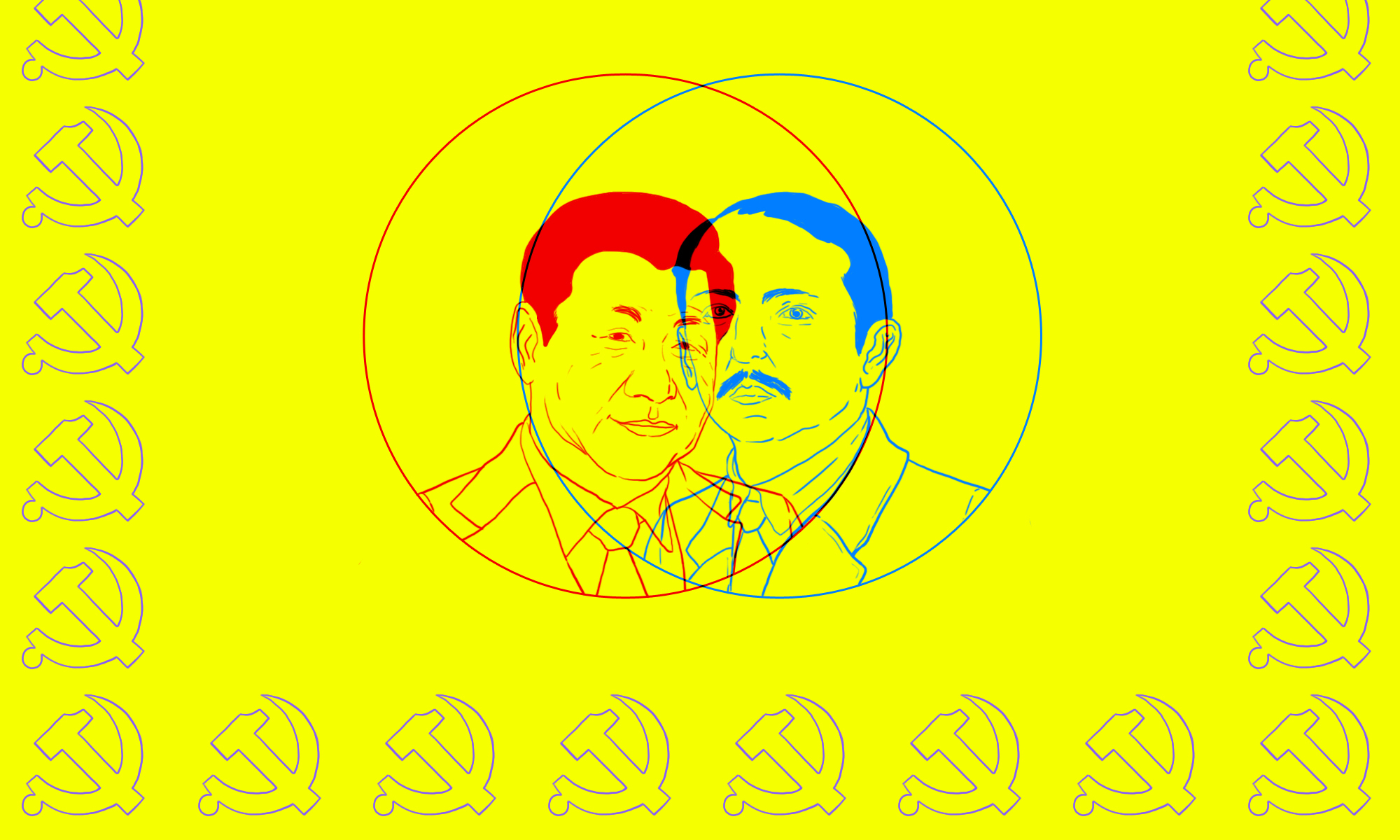

From Sneevliet to Xi: How Chinese communism has endured and evolved over 100 years

In this transcript of a Sinica Podcast episode marking the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, three contributors to a book about 10 key figures in the CCP’s history have a wide-ranging discussion about the Party.

In the July 1, 2021 Sinica Podcast episode marking the 100th birthday of the Chinese Communist Party, Kaiser is joined by historian Timothy Cheek of the University of British Columbia, political scientist Elizabeth Perry of Harvard, and our very own Jeremy Goldkorn, editor-in-chief of The China Project. The three each contributed chapters to a new volume called The Chinese Communist Party: A Century in 10 Lives, edited by Timothy Cheek, Klaus Mühlhahn, and Hans van de Ven.

A full transcript of the episode can be found below the audio embed. You can subscribe to the Sinica Podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or any other podcast app.

Kaiser Kuo: Welcome to the Sinica Podcast, a weekly discussion of current affairs in China produced in partnership with The China Project. Subscribe to The China Project’s daily Access newsletter to keep on top of all the latest news from China from hundreds of different news sources, or check out all the original writing on the site at supchina.com, including reported stories, editorials, and regular columns, as well as a growing library of videos and of course podcasts. We cover everything from China’s fraught foreign relations to its ingenious entrepreneurs. From the ongoing repression of Uyghurs and other Muslim people in China’s Xinjiang region to China’s ambitious efforts to eliminate poverty. It’s a feast of business, political, and cultural news about a nation that is reshaping the world.

I am Kaiser Kuo, coming to you today from my home in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Joining me from stately Goldkorn Manor in the tony suburbs of Nashville, Tennessee, is a man who was recently outed as a Jiang Zemin fetishist. In fact, I think a Jiang toady, as they say, Mr. Jin Yumi.

Jeremy Goldkorn: Hey, Kaiser.

Kaiser: How’s life post vaccination for you, man?

Jeremy: Yeah, it’s pretty good. I have to say, I didn’t realize quite how much I miss talking to strangers.

Kaiser: Yeah. Jeremy, for those of you don’t know him, he’s notoriously misanthropic. He was a sociopath. He was the guy we always say when I’d want to go get a beer after a taping of the show. Let’s not go there. No one goes there, there’s too many people. That’s what he used to say. Anyway, Jeremy, this is kind of a tease actually because you’re not actually going to be co-hosting today but rather you’re playing the role of guest, because you’ve written a chapter and a very good one, I thought, for the book that we are discussing today.

This month marks the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party. And to mark the occasion, Cambridge University Press has published an excellent volume called The Chinese Communist Party: A Century in Ten Lives. It has outstanding contributions from some of the leading historians and scholars of politics working on China today, and from Jeremy. The book was edited by Timothy Cheek, Klaus Mühlhahn, and Hans van de Ven. And I am delighted to be joined today by one of those editors who also contributed an essay, Timothy Cheek. Tim is a Professor of History at the University of British Columbia and is the author of among many publications, The Intellectual in Modern Chinese History. Tim, welcome at long last to Sinica, great to have you.

Timothy Cheek: Well, I’m delighted to be here and I’m a fan.

Kaiser: Oh, fantastic. Well, I am too. I am also joined by Elizabeth Perry, who is easily one of the most highly regarded scholars working on Chinese history and politics. Liz is the Henry Rosovsky Professor of Government at Harvard University and serves as Director of the Harvard-Yenching Institute. She’s an incredibly prolific writer who has published some two dozen books — more — on a wide range of topics on modern Chinese history and politics in English and in Chinese, I should add. Liz, welcome to Sinica and great to finally have you on the show.

Elizabeth Perry: Thank you so much, it’s a pleasure to be here.

Kaiser: Well, fantastic. I’m really glad we could all assemble.

All of you are frequently asked to talk about the Chinese Communist Party to audiences that perhaps aren’t as familiar with that institution as our listenership is. (Actually our listenership isn’t even that well informed about the Party, to judge by some of the questions I field from people who profess to be listeners but ask me some very strange questions!). And so if you had to liken the CCP to any other extant institution, historical institution that might be better known and better understood, what would you liken it to? I mean, or is it in its current incarnation simply sui generis?

Elizabeth: Well, okay, if you were to ask me, first of all, the answer I would give you would be one that my colleague when I used to teach at the University of California at Berkeley, Ken Jowitt, always gave. Ken was a specialist on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, and to him, the obvious analogy was the Catholic Church.

Jeremy: Yeah, absolutely.

Elizabeth: Ken, himself had grown up in the Catholic Church and he felt that the combination of concern for ideology and concern for organization and control were remarkably similar. I didn’t grow up in the Catholic Church, I grew up in the Anglican Church, so a little more relaxed, a little less controlling. And probably the most controlling environment I’ve existed in is Harvard University, where everything actually is centrally controlled and there is a myth of faculty governance and all sorts of institutions that in theory replicate the mass line but the reality is all the decisions are centrally determined. And actually I’ve found existing within the Harvard bureaucracy to be remarkably helpful for understanding some of the operations of the Chinese Communist Party, but I’m sure other analogies come to the minds of our co-authors here.

Kaiser: Yeah, Tim. I mean, I did half expect somebody to come up with the Catholic Church, I’ve used that with myself.

Timothy: Yep.

Kaiser: Well Tim, but Harvard?

Timothy: Yeah, yeah, that was a new one for me.

Kaiser: Yeah, me too. Me too.

Timothy: I’m with Liz and Ken at the Catholic Church and I find it most useful for exactly the reasons that Liz gave. But being a historian I think more of the Catholic Church historically when it was saving souls, burning sinners, and running armies.

Kaiser: Oh, right, right, right.

Timothy: And if you think of the early modern period, and so the Party, it is a bit like that. It’s helpful to think about because we easily get into very dark terminology about the Communist Party and totalitarianism. And with the Catholic Church, we have deeply mixed feelings, it does some good things it does some bad things.

Kaiser: That’s right. That’s very well put. Jeremy, you want to weigh in here?

Jeremy: I absolutely agree with the Catholic Church, I think that’s the best way to describe the Communist Party to somebody who doesn’t know anything about it. I think the mafia is also another good way. It’s a very secretive organization, very hierarchical. They do provide goods and services. Mafia organizations often do necessary things for immigrant communities that the government isn’t providing.

Kaiser: As the Muslim Brotherhood does.

Jeremy: They are organized. They have a code of absolute loyalty. If you cross them there’s a bullet with your name on it, so I think that that’s pretty good. I know there’s a side of you that would hate that analogy because the first thing that springs to mind is the worst aspects of the mafia, but the mafia organizations, criminal organizations, triads, they exist for a reason, so a good mafia.

Kaiser: Okay. Well, let’s get into the book, and I want to ask you guys how the volume came together. I mean, it made sense of course to want to do some sort of an anthology commemorating the Party at its centennial, but how did you settle on this decade by decade approach and an approach that’s centered on individuals who sort of represented the zeitgeist of each of the decades?

Timothy: Well, it started a number of years ago, about three or four years ago. And Liz will remember that we invited you to Berlin, I think in August of 2018, and you and Hans were about the only two who couldn’t make it but were interested. Klaus and I were trying to pull together people interested in the Communist Party, looking forward to the 100th anniversary and saying, “Well, Xi Jinping, if he’s done nothing else, has reminded us that the Party is not going anywhere. And what are people writing about?”

So we brought people together from China, we had a couple of Chinese scholars from PRC at that time, which was great. In fact, one of our contributors, Xu Jilin and Ishikawa from Japan and others, and we were simply overwhelmed because there’s excellent new research being done in the last 20 years by scholars inside China and to do a comprehensive was beyond us, and so I didn’t know what to do. And then Hans said, “Why don’t we do something like the BBC A History of the World in 100 Objects?” And my answer was, “We all would like to write a book like Timothy Brook, but we know we can’t, but we could write a chapter.”

Kaiser: Right, right, right.

Timothy: We decided one person, one decade, to try to show the change over time. My big shtick is contingency and that each ideological moment or each decade can be quite different.

Kaiser: Indeed. Quite different but then there still somehow are themes that emerge when you look at the book in total, and then, so let’s get into the content of the book itself to which all three of you contributed chapters. The first two essays, for example, and we could speak with them together because they both look at chapters in the forging of, well, United Fronts, the first and the second United Fronts between the Communists and the Nationalists.

In the first Tony Saich looks at this character, Hendricus Sneevliet, a Dutch Comintern agent who is present at the creation as it were of the Party. He wasn’t on the boat but he was in the original pre-raid meeting in the international section in Shanghai. He was also instrumental in persuading the nascent revolutionaries of the need to collaborate with the Kuomintang to become a bloc within the Nationalist Party. The second chapter is an essay by Hans van de Ven, who’s one of the editors, about Wang Ming, who was very urbane, very erudite, very Westernized, who’s one of the 28 Bolsheviks. He pushed a solidly pro-Comintern line, came to clash with Mao. And it seems to me that something in common here is that both of these two represent a kind of cosmopolitan tradition in the CCP. And not just in those chapters either, we see other characters who bring this later on, I mean 60 years later in the chapter in the 1980s, for example, the character of Zhao Ziyang. Can we talk about this cosmopolitan tradition and whether that was a theme that you deliberately wanted to hit maybe in response to — I think that’s something probably a lot of people don’t know about the history of the Party.

Timothy: Mm-hmm (affirmative). We started with an inductive approach being the three of us historians and just said, “We’re going to have the two narratives. It’s going to be ‘the Party is wonderful’ coming out of Beijing and ‘the Party is awful’ coming out of Washington.” And we wanted to strike some kind of path in between as historians. And so we said, “Just look and let each author tell it like they see it in their time period.” This was not Liz’s chapter but Liz has dealt with 1920s, its cosmopolitanism and commitments from on Anyuan. And so how did that theme strike you, Liz?

Elizabeth: Yeah, I recall, I think Tim, that at first you had suggested that I might work on the 1920s and do a possible chapter on Li Lisan, I had kind of portrayed as the hero of Anyuan in my book on the communists at the coal mine. And I think I replied to you that I really had said everything I had to say about Li Lisan, and since I was currently working on the 1960s and work teams, I wondered if switching to a different character might make sense. But my guess is that the cosmopolitanism of it is a reflection of the fact that you really did give us pretty free reign to choose the characters whom we found attractive and not surprisingly, most of us are probably most attracted to some of the more cosmopolitan figures in the history of the Chinese Communist Party, some of whom are not Chinese. Several of these characters in the chapters, Dutchman and also Guzman—

Kaiser: A Peruvian

Elizabeth: —I think makes an appearance later on. And so we have people from Latin America, people from Europe and then Chinese who themselves have spent a lot of time abroad and speak foreign languages, who I think to us as foreigners studying the Chinese Communist Party are particularly interesting characters to think about how they responded to the opportunities and also the problems that were presented by the Communist Party in each of these decades.

Kaiser: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Well put, yeah. So they may not be perfectly representative but they certainly do represent a facet of the history of the Party that too often I think goes ignored. The big question that I’m always asked and I feel like I’m constantly wrestling with, and I know it’s not an easy one, is the Party better understood today more in terms of its continuities or its changes? I mean, there are those who see the Party in its current incarnation as very much the same Party that existed under Mao. They emphasize its Leninist form, its authoritarian inflexibility. On the other hand, there are plenty of people now who would emphasize instead the big ruptures. Its completely different composition before and after Deng and its ideological flexibility, and its flexibility is a source of its resilience. I’m often torn, I think, but that it’s kind of a litmus test. Those people who do fall on one side and fall on the other you can see an awful lot about how they approach China. I mean, I know that you’ll all want to say both in answer to this, but let me ask specifically, Liz, first.

Elizabeth: I mean of course I do have to say “both” because the Party could not possibly have survived without reinventing itself at various junctures. And we can look at a number of those key watersheds of change. And one that I think is particularly important is Jiang Zemin’s “Three Represents” that everyone used to laugh at in the 1990s, but it is —

Timothy: Yes. I thought I was the only one who—

Kaiser: My God, I have a big question all about that and that’s exactly my thing.

Kaiser: Yeah, that’s exactly how I couched it too — just how it’s such an object of scorn and ridicule at the time.

Elizabeth: Yeah, everybody called him a clown, but it was profoundly important to say that people who are capitalists can actually be invited into a Communist Party. And so it was very heretical, but it also it’s suggested that this Party was going to be the representative of advanced forces in society, both economically and also scientifically and intellectually. And I think that that has been profoundly important. So there are these extremely important changes that have helped to reinvent and rejuvenate the Party, and yet overall, I would see it more in terms of continuity and particularly under the current general secretary, because I think that Xi Jinping himself really does look to the history of the Chinese Communist Party for his inspiration. And he often quotes Mao and refers to Mao and frequently is likened to Mao. But as I and I’m sure a number of others have suggested, he also looks a lot like people who Mao eventually broke with and most obviously Liu Shaoqi who, like Xi Jinping, was a control freak and who wanted the Communist Party to be in charge of everything and was quite willing to mobilize masses for support of the Party but did not want that mobilization to get out of hand. That’s very different, obviously from Chairman Mao who had the confidence to think that if things got out of hand he would be able to bring them back into the kind of order that suited him best, and repeatedly showed that that was the case. But I don’t think either Liu Shaoqi or Xi Jinping has that kind of confidence. And in my view, a lot of what Xi has done in the anti-corruption campaign is very reminiscent of what Liu Shaoqi did in the socialist education movement, the Four Cleans leading up to the Cultural Revolution, which was also very much an anti-corruption campaign and effort to reimpose the control of the Party over all aspects of society. And also Liu Shaoqi tried to develop a kind of cult of personality of his own, in that period, just as Xi Jinping is developing his own cult of personality today. And so really, from my point of view, at least without understanding that history it’s very difficult to understand where the Party currently is coming from because I think the Party is deeply conscious of that history. It’s a long history now of a century and obviously a very eventful history so there’s a lot to pick and choose from. It’s not as though it by any means is deterministic. It rather opens doors and opportunities and so forth. But it also sets limits to imagination when you have general party secretaries who are less inventive. And so I see the continuity has been central but not determinative, yeah.

Timothy: And one of the themes that comes up in the book, and Klaus loves to hammer on this one is that it’s a learning party. And look at the changes, part of the way it could survive organizationally is it wasn’t afraid to go back on itself and flip-flop was not a problem for them. Of course, when you run the propaganda system no one’s going to quiz you on your flip flop. So it goes from an urban party to a rural party. A rural party to a Soviet-style administration. Then it’s going to go anti-Soviet and then it’s going to bring in a bunch of market reforms and all under the Communist Party.

And I’m with Liz, I’ve been saying for a while too that put away your Mao Zedong quotations and get out. I have a little red volume of Liu Shaoqi on lun dang (论党), and it includes the long version of on self-cultivation of the Communist Party member. And it’s very much that the second thing that Liz said I think is key, and this brings us back to the Catholic Church, the san ge daibiao (三个代表), the “Three Represents.” That’s like the Vatican II.

Kaiser: Vatican II.

Timothy: It is explaining to the faithful why something as awkward as having capitalists in the Communist Party is theologically okay. And finally, the way I see Xi Jinping is I call it “Xi Jinping’s Counter-Reformation.” Again, thinking Council of Trent.

Kaiser: As opposed to the Edict of Nantes.

Timothy: And what’s he going against? He’s going against the Reformation, the reformed Leninism of Zhao Ziyang. And then going into Jiang Zemin, but we’ve got someone here who can talk about Jiang Zemin.

Kaiser: We do, and indeed. Actually we flicked at two later chapters where we will be talking about Jiang Zemin, Jeremy’s excellent chapter. And Liz also flicked at the “Four Cleans” so we’ve got “Three Represents” and “Four Cleans,” and we’ll get to both in a little bit. Something that’s always struck me about the Party across its century of history is this oscillation between periods of admirable, ideological flexibility, where it’s really able to set aside dogma in deference to practical reality and these other periods of retrenchment or ideological rigidity. Explanations though, I mean, and this is something we very much see: they boil down too often, I think for my taste, to the individuals at the top of the Party organization. Mao was dogmatic, Deng was a pragmatist, well, with the black cat, the white cat, the feeling with stones and blah, blah. And then Xi Jinping came and we’re suddenly back to rigidity. I feel like people looking at China today are more apt than ever to find explanation in personalities of leaders, but I’m kind of less of a “Carlylian” and more of a “Tolstoyan” when it comes to this. And so this has never been very satisfying to me. Is there a better way to think about these oscillations? Tim, you talked about how Hans has talked about it, it’s a learning party, and that I think those take us away from that individual thing. Can we expand on this? What are your thoughts on the individual versus historical forces and the shaping of flexibility?

Timothy: Well, I think one way to think about it is the tension between the supreme leader and collective leadership in the Party and that’s definitely a theme that goes throughout the history. I’ve long seen that even Mao Zedong coming as the supreme leader — part of that was contingent. Of course, the Communist Party in China is based on the Stalinist model, Bolshevik Party, but they didn’t make Chairman Mao, Chairman Mao, until ’43/’44 when they were up against Chiang Kai-shek being the lingxiu, the Fuhrer, and his book China’s Destiny. So the Communist Party had to have an Elvis Presley figure out front to get everyone dancing. And I think that that’s an agreement that has come amongst the Party elite now, 50, 60 years later in a completely different situation, why is Xi Jinping able to do what he’s doing? Is it because he’s so brilliant? Is it because he’s so charismatic or is it because the leadership has decided that the Chinese political culture needs a figure like that?

Kaiser: Right. During the Hu and Wen period of course I think we would have looked at the collective nature of the leadership and decided, well, that’s a feature, that’s not a bug. This was also a deliberate choice. This wasn’t just a function of Hu being weak, this was something that they believed that they needed at that time but it allowed a lot of things to happen that I think a lot of people-

Timothy: Well, the way to look at it too is we look back at the Jiang Zemin’s extended reign, the post reign in the 2000s and the “naughties,” the naughts, but many of the repressive policies that are in line today came with the youth league group around Hu and Wen. They were started and they’ve only just been perfected.

Kaiser: Yeah.

Elizabeth: Yeah, the stable maintenance regime really was put in place in 2008.

Kaiser: Yeah, that’s when we all started talking about harmonization.

Elizabeth: And partly the lead up to the Olympics, partly the unrest and Xinjiang and Tibet. And clearly there was a great concern on making sure that the Party did not lose control at that moment, and also obviously the financial crisis, international financial crisis. All of those things made the Party very nervous and that certainly predated Xi Jinping’s term.

Kaiser: And, Jeremy, I want to bring you in here because, I mean, I think your chapter, I was very pleased to see, recalls the decade that we’re just talking about the decade of the “naughty aughties” as you call it. Very much in the way that I do, I mean, it was in a sense “our” decade. I mean, right at the heart of the years that we spent living in China, you from ’95 to 2015, me from ’96 to 2016. I mean, it was right in the middle of it. I mean, I feel like the early years of our show too, Jeremy — we were taping in that really awful apartment in Beijing — they documented or maybe chronicled that whole shift away from the spirit of those earlier years. We jokingly, and actually you even referred to it in your book, we’ve had a golden age of liberalism.

Jeremy: Yeah, I mean, did I cite you as the source of that quote or did it come from me?

Kaiser: No.

Jeremy: I don’t know but we used to talk about it.

Kaiser: It came from you originally. I think you were the first one that —

Jeremy: We used to talk about that a lot on the show. And I mean, indeed our first show in April, 2010 was about Google leaving China, which was kind of that was one of the signs of the end of that era because they’d come in 2006 and there was this feeling that there were possibilities of openness which closed, and that did predate Xi.

Kaiser: I got to ask you, Tim, the choice of Jeremy was an interesting one. I mean, I would’ve gone with him because I think that if you were to look at the newspapers of that era, he was probably the most quoted person. He was the guy with his finger on the pulse of what was happening in this new public sphere of the internet. If you had a question about what people are saying online you got to ask Jeremy Goldkorn. I mean, Danwei was really doing that. I mean, you had the sense of the zeitgeists then so I thought it was a really good choice.

Timothy: Well, Kaiser, it was an obvious choice. Here was Jeremy Goldkorn, was this Sneevliet of the 21st century! He was the messenger of historical nihilism. He was just bringing in the most advanced stuff from the West.

Kaiser: Right, right. He was the flies that-

Jeremy: I didn’t know if I like the way this is going.

Kaiser: He was also— Yeah, he was the guy who’s picking quarrels and causing trouble.

Timothy: But the real answer is too we wanted to break out of all academics. And there’s very valuable knowledge about China that comes from people who do other than write dissertations and sit in a library. And so it was your active work particularly in that decade and living there and the lived experience that you had in your engagement that was very attractive for us.

Kaiser: Yeah. I thought it was a pretty inspired choice, I would say. I mean, not just because he’s my buddy.

Timothy: And then we went with Yang Guobin.

Kaiser: Oh, that was great too. His choice!

Timothy: And what he did, he confessed with Guo Meimei.

Kaiser: Guo Meimei, yeah. That was fantastic. I mean, we will talk about who Guo Meimei was, actually this is a tradition on our shows whenever we have some pop culture figure that shows up the first thing out of my mouth is, “Jeremy, would you like to do a quick explainer?” Before we ask you to talk about Guo Meimei and Yang Guobin’s piece, Jeremy, let’s talk a little bit about the “Three Represents.” And then your choice of Jiang as the person to focus on, that was interesting. I mean, it wasn’t some internet entrepreneur, it wasn’t some emerging public intellectual, it wasn’t somebody symbolic like Sun Zhigang, well, they all would have been legitimate choices like you could have gone with Jack Ma. You could have gone with Fang Zhouzi or something like that.

Jeremy: Yeah, I suppose so. I mean, I think part of it was that as soon as— I think it was originally Tim and Hans contacted me about the book, Jiang Zemin was the first person I thought of because I am a “toad fan.” I am somebody who’s slightly obsessed with Jiang Zemin. And it also seemed to me that he was hanging wraith-like over much of my experiences of China. That he was this sometimes visible but usually invisible presence over the government, but over even the things that I was doing in China. The way people were interacting, the fact that there was this crazy capitalist boom that he was partly, or perhaps largely responsible for with the “Three Represents.” And that he also captured the imagination of a later generation of younger Chinese internet users who weren’t really observing politics when he was actually in power, but he’s become this almost cult figure. It just seemed that he symbolized a bunch of different things about the changes in China and particularly the Party’s role in it.

Kaiser: Jeremy, the “Three Represents” when it was rolled out initially was something that I think both of us recognized as significant, but at a time when most of our friends, foreigners and Chinese alike, were really dismissive of it. I mean, okay, let’s face it, it was inelegantly packaged. I mean, looking back though, I mean, do you feel as confident as we were back then of how significant enduring a theoretical contribution this was that was made by comrade Jiang Zemin? The Party core. Do you feel-

Jeremy: I don’t think I’m the right person ask about the value of the theoretical contribution, I think you should ask a proper historian about that, but I think in terms of shaping the times, yes, I think it was very important. I mean, the company you used to work for, your old boss, Robin Li, literally used to and maybe still does attend meetings of the Consultative Conference, right?

Kaiser: He does.

Jeremy: I mean, that’s extraordinary. In the early 1990s when people thought maybe, before Deng died, people thought things were going to go really backwards and a lot of this experimentation with capitalism would end. Who could have imagined billionaire business people in— I mean, I know it’s a weak and impotent part of the government, but still. So yeah, I don’t—

Kaiser: It’s not the Party either.

Jeremy: No, but—

Kaiser: But I take your point, absolutely. I mean, what really changed my mind on it and I’ll just tell a quick story, that I may have told before, was that I was talking about it with my father who also lived in China and he was the first person to truly alert me there’s a difference because I had said something sneering about it. And he said, “I recently visited a company in Zhongguancun that employs 12,000 people. Only three were Party members: one was a driver, one was a chef, and the other person was just some middling person.” And he said that anyone who looked at that situation would recognize that that was untenable for the Party. That if you have an electronics concern, a very, very lucrative one, and it had such low level of Party representation, that that was not going to work. That alerted me to it and then I started watching as this was happening. I wanted to ask you about Yang Guobin’s chapter and about this character Guo Meimei. By the way, no relation.

Jeremy: You say!

Kaiser: What did Guobin see in her story that made her such a good vehicle for discussion of the decade of the 2010s in China, Jeremy? Maybe could you give a quick potted history of this scandal-ridden woman?

Jeremy: Well, I mean, I can’t speak for Guobin but I do think it was a genius selection. She was a young woman who had a Maserati and a lot of very expensive clothes and accessories and used to show them off on Weibo, China’s Twitter, the premier social network of the time. And this was very common behavior. There was a word for it, shai fu (晒富), to show off your wealth. But she made the mistake of having in her bio that she was working for the China Commercial Red Cross Society, I think it was called. I may have got those wording, not exactly.

Kaiser: Yeah, you’re close enough. It had association with the Red Cross.

Jeremy: It had apparent association with the Red Cross. And this was before Xi Jinping destroyed the internet as we knew it and there was still a very, very lively debate on social media and Weibo was very active and there was this bulletin board website forum called Tianya where there’d be a lot of slightly investigative work by groups of internet users. And somebody pointed out that this woman who appeared to be being paid by the Red Cross was buying Maserati’s with the money or some money, and it became a controversy on the Chinese internet. She was “human flesh searched.”

Kaiser: “Flesh searched.”

Jeremy: People dug her up and the Red Cross actually lost a lot of money, the Chinese Red Cross because people stopped donating.

Kaiser: Yeah. Blood supplies were very low. All of a sudden, it was just terrible.

Jeremy: Everybody had to apologize. And then she was eventually in 2015, a few years later, she was done for on gambling charges and then sentenced. She did five years in jail and had to do— she was one of the victims of the televised confession campaign on CCTV that became a hallmark of the early years of the Xi Jinping administration.

Kaiser: That’s right, that’s right.

Timothy: But she was a perfect poster child for a theme that we were struck by in the 2010s, which is how far away the Party was. And just like your father’s story, it sets the grounds for what Xi Jinping is on about, which is, this is out of hand. We have to get back and control, and the spirit of Liu Shaoqi, as Liz said, has risen again.

Kaiser: And it’s, once again, grasp the essential. Tim, I want to turn to you and talk a little bit about intellectuals and their relationship with the state, with the Party specifically, the chapter on Wang Yuanhua and your own chapter on, Wang Shiwei, for example. You’ve built a career on looking at the state and intellectual in China, which I have long held to be one of, if not the most important key to understanding how politics, how history move in China. This collection isn’t an intellectual history but it does zoom in on some important inflection points in the relationship between Party and intellectual, again, including your chapter on Wang Shiwei on the rectification campaign. Can you quickly maybe identify across this 100 years for you what the less obvious inflection points are? And we all understand some of these moments, we all understand the Hundred Flowers and then the anti-rightist campaign. We all understand these things, but what are some of the other more subtle moments when the relationship between Party and the zhishi fenzi has kind of started to shift?

Timothy: Well, you’re right. It’s been a career for me and it’s endlessly fascinating. And one of the key things is of course that most of the Party leaders were intellectuals and yet they were criticizing intellectuals. And so Susanne Weigelin-Schwiedrzik said what we think of as struggles between the Party and intellectuals are just struggles amongst intellectuals. The key thing here is Wang Shiwei in the 1940s, he goes down as a critic of Mao, but what he was doing, he was very much in the group of Wang Ming, not as a direct follower but in the same worldview of this cosmopolitan communism that they said, “This is part of a global revolution and it’s going to be modern. And so national forms is crazy, you’ve got to have Western forms because they’re the most modern.” And so the deal that was hammered out there was as you do it Mao’s way or no way. And yet plenty of people— I also worked with Deng Tuo who was the first editor of People’s Daily. They found a rich life serving the Party and being know Chinese intellectuals and collecting art and doing these things in the 1950s, and then it blows up. I find the most poignant work is actually the ’80s with Wang Ruoshui, who we did not profile, who was a leftist in the Cultural Revolution, took down Yang Xianzheng and others and had his houhui. He had his regrets. And even Zhou Yang, Merle Goldman’s bete noir, the literary czar, they’re trying to rethink what they’re doing. And so the book that captures this relationship so well is Miklos Haraszti, The Velvet Prison: Artists Under State Socialism, which was translated in 1989. And we all learned about it from Geremie Barmé when he wrote about the “velvet prison” in China and that is the attractiveness of the state socialist system for intellectuals to be the teachers of the masses. The attractiveness of Stalinism and socialism for intellectuals is that you get to be the teacher of the nation. And look at Liu Binyan. Liu Binyan, what did he say? “We have to speak for the people.” And that’s why the chapter by Xu Jilin on Wang Yuanhua is so powerful. Because Wang Yuanhua was like Wang Ruoshui, a loyal lefty, super smart, super cosmopolitan, he loves 19th century European literature, he served the Party and by the ’90s, he’s an apostate.

Kaiser: Yeah. But he’s still an apostate within a scripted way and the elliptical way that he deploys language and all that, which is just it comes across in Xu Jilin’s piece on him. I thought it was a really good study of the way that the state and the intellectual typically interact. And this isn’t just within the history of the hundred years of the Party’s history. I think this goes quite far back where you could describe it as loyal opposition, where remonstrance against the state takes on this allegorical, very highly symbolic form. It’s quite subtle, it requires actually a pretty good steeping in the culture to be able to read this kind of arcane semiotic language sometimes. But Liz, I mean, maybe we can talk about this because this is your playground as well. Throughout the whole history of the PRC there’ve been lots of examples of this. I mean the obvious ones like “Hai Rui Dismissed from Office,” this oblique defense of Peng Dehuai after he criticized Mao, the invocations of May Fourth during the ’89 protests all over the place. Do you think that this very culturally-specific political idiom, the requirements, the understanding of the symbolic language that’s deployed by intellectuals, this makes Chinese politics I think, particularly difficult to understand, really inaccessible to most people. And how as a professor of politics and history do you try to give your students a sense of this?

Elizabeth: Right. I mean, we’re very lucky these days in that so many of our students are actually from China and have native fluency in Chinese and can help us out in this respect. I think the question of political allegory is one that we find in lots of authoritarian regimes, especially those that have long histories in which people then write in arcane code that is accessible only to those who are really well-versed in the culture in which that particular political regime is set. So I don’t think that’s uniquely Chinese. I think we, we see it in different cultures, but in order to understand it in any particular culture, you have to be able to go back to the historical analogs that are being referenced. And I think students in fact find that quite fascinating, but I would say as you and Tim were talking it occurred to me that one of the first questions you asked, Kaiser, was about continuity and change in the Chinese Communist Party. And, Tim, of course quite correctly reminded us that the Party from the beginning was a party of intellectuals. These were intellectuals who gathered, who were deeply concerned about the fate of their country, but they included some of China’s leading intellectuals, so the head of the Peking University Library, the Dean of Peking University. Even Mao who certainly could not have been considered a leading intellectual nevertheless had had an excellent education and became known for his calligraphy and his poetry and his ability to reference these kinds of things. I don’t think we could say the same about Xi Jinping. I think we’re talking about a general secretary today who due in large part to the Cultural Revolution is not terribly well educated in his own culture. People have laughed at his mistakes when he’s reading somewhat obscure Chinese characters in a speech and reading them out incorrectly. He’s helped by people like Wang Huning and others who guide him on his ideological journey. But I think this is one real difference of the Chinese Communist Party today, that it’s not led by someone who really is an intellectual. That may have been true for Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao as well, at least they were well-trained as engineers. But if we go back earlier to Deng Xiaoping, Mao Zedong, we are talking about people who enjoyed exchanging ideas and who were searching both in their own history and in Deng’s case being trained abroad, spending time in France and that was true for many of the other early Party leaders as well, that they were looking not only into their own history but they were looking around the world for various kinds of ideas and analogies. I do think that’s something that does not bode well really for the future of the Chinese Communist Party, to the extent that now it has more of the sort of apparatchiks that brought down the Soviet Union, people who really did not come across as intellectuals, people who understood how parties were supposed to be run and we’re very concerned about controlling them, but had difficulty with soft power, if you will, difficulty with referencing the more subtle messages in their culture, let alone reaching out in a cosmopolitan way to be able to incorporate foreign ideas within it. And so I think that is one of the worrying concerns for those who would like to see the Chinese Communist Party survive well into the future. In my view, it looks today with somebody like Xi Jinping in charge a lot more like the Soviet Union’s party. And I think it’s maybe a little less difficult to interpret it than it was in Mao’s day when you had to pull out your 24 dynastic histories and look for those references in his poems and so forth. You don’t really have to do that with Xi Jinping’s speeches.

Kaiser: No, you don’t.

Elizabeth: And so I think in some ways it’s quite ironic because Xi Jinping of course is constantly referencing Chinese history, the 5,000 glorious years of Chinese tradition and how the Chinese Communist Party is the sort of seamless continuation of that glorious history. But I think the reality is that his own familiarity with that history is not particularly deep, and that that’s perhaps a concern for the future of the Party.

Kaiser: Oh, you have to be careful what you wish for. I mean, I’m not sure that we want, Wang Huning or Hu Angang or anyone else succeeding him, they’re the actual intellectuals.

Timothy: They’re intellectuals but I’m not sure they’d be my best friends.

Elizabeth: I mean, the top leader of the Party has never been someone who was chosen for his intellectual prowess, it’s always been somebody who could win the street fights, I think there’s no question about that. But having that person be able, nevertheless, to present things in a way that were culturally consonant I think that has been very powerful and very important to the success of the Chinese Communist Party. And if it just has the street fighter but that street fighter is really not able to put his fingers on the pulse of the Chinese cultural tradition, I think that’s a real vulnerability for the Party’s resilience.

Kaiser: Yeah. I mean, it’s just, I suppose, do we need— I don’t know. I mean, I don’t know how the intelligentsia would respond to one of its own right now either, it’s hard for me to guess. I can imagine them maybe even being more offended if he did have those pretensions. And maybe we do need the street fighter, the guy who has some abilities in retail politics for the time that we’re in. But, hey. I want to on with this topic of intellectuals with you, Tim.

One of my gripes, one of my big gripes, and Jeremy’s heard this a million times, and this is really one of the reasons I admire your work, and the work of people like David Ownby, is that especially since ’89, the China-watching world has tended to focus on critical intellectuals, not the Party intellectuals that you’ve made your bread and butter. They focused on the dissidents almost to the exclusion of the more establishment intellectuals, whether Party or not Party. Okay, they’re far less sexy than the dissidents or the critical intellectuals.

Jeremy: Less sexy, more stoogey.

Kaiser: Yeah, but you could make the case that they’re also, or even maybe even more, critical to understanding China as it is. Your chapter, you went with Wang Shiwei who, as a victim of the replication campaign, is more in the mold of critical intellectuals who usually get the attention. Can you talk about your decision to focus on him? And that deviated from your typical approach, which is like, you’re going to bring out this boring guy and you’re going to show us how, actually, if we understand how he thinks we do a better job or get a better read on China’s reality?

Timothy: I know when I pitched my dissertation topic to Phil Kuhn, I said, “Well, Deng Tuo, he’s a dead communist propagandist, what’s not to like?” And then we won them over in the end. Wang Shiwei, from Merle Goldman on down, has been a poster child, a figure for dissident intellectuals. And it was my old teacher at ANU, Pierre Ryckmans — Simon Leys — who put me on to him. And I have to say for Dr. Ryckmans’ benefit I didn’t come up with the answer he expected me to come up with because he considered Wang Shiwei a paragon of morality who showed the banality of Mao and the Party.

And what I discovered was, yeah, he did, because he thought their communism wasn’t communist enough. I still consider him part of my establishment intellectuals and he was working within this language. He was just brash out of Shanghai and didn’t realize that he was on the home turf of the biggest street fighter as Liz put it, and of course went toe to toe and lost on it. But all the way down. I am with you. I think if we want to understand the ideology as it rolls around China’s political sphere you need to hear more voices. And you mentioned David Ownby, and I was about to do a shout out for “Reading the China Dream.” If you want to find out thousands of pages now in English of a diversity of Chinese public intellectuals, new left, liberal, new Confucian, and others, that it’s a great source for people and there’s no excuse for saying, oh, I can’t read Chinese fast enough, there’s plenty of voices there, so Hu Angang and the lovely Zhang Shigong are represented well, along with another range of voices.

Kaiser: Jeremy, do you remember how Jude Blanchette put it, he said, “Who is the David Brooks of China?” I thought that was so brilliant. It was like, we need to understand who the most bland centrist— and Brooks isn’t stupid, but uh— Anyway, I want to move back to Liz and get her to talk about her fascinating chapter about Wang Guangmei. Wang Guangmei was the wife of Liu Shaoqi, who’s his fourth or fifth wife, I think. I guess I didn’t realize that guy went through so many wives, but for those who aren’t up on your Party history, Liu Shaoqi who we’ve talked about him a little bit before he was— By the way I cut my teeth in Chinese politics at UC Berkeley with Lowell Dittmer who wrote the book on Liu Shaoqi. He was a very familiar character to me growing up. He was made of course the first major target in the Cultural Revolution and he died in prison. Wang Guangmei herself was also a victim of Red Guard violence. She actually endured one of the most humiliating and largest public struggle sessions and then there’s famous pictures of it and they’re included in the book, you should see this is really distressing to see the necklace of ping pong balls and the big straw hat. But the central irony in your chapter was about how Wang Guangmei actually helped really set the stage for it, really maybe uncorked the bottle of the Cultural Revolution. Can you tell us about that, Liz, about the “Peach Garden Experience” that was just part of this “Four Cleans” campaign that her husband had launched? How she went incognito to a little village to try to uproot official malfeasance and ended up letting out the demon.

Elizabeth: That’s right. Wang Guangmei had had some experience in mobilizing society before the socialist education movement. During land reform she was one of these intellectuals who had gone to Yan’an and had then been assigned to go down as a Communist cadre to help classify land and so forth. And she actually served during land reform in an area that became very well known for its violence and bloodshed, so she had already learned a thing or two about mass mobilization. But she apparently was quite surprised in the mid-1960s when her husband, Liu Shaoqi, insisted that she should go down to some village in China. He was not specific where it should be to help carry out the so-called “Four Cleans,” the Si Qing (四清) Movement, that was supposed to clean up our cadre infractions at the grassroots. And Wang Guangmei had, as I said, had this experience during land reform but she had also been quite chastened during land reform at her inability to understand the local dialect of the peasants in Shanxi Province where she had been in land reform. And later on right after the Great Leap Forward she had accompanied her husband down to his native Hunan Province and she was even more distressed there that she could barely understand a thing that the peasants were saying in Hunan and they could not understand her either.

And so when it came to the “Four Cleans” she chose a village in north China where she would actually be able to communicate with the locals. And she went down incognito with a pseudonym claiming to be a security cadre from Hebei Province. And she tells us in her memoirs that because television was quite rare in China at that time, most people really had no idea who she was for at least the initial stage of her time in this village. But like many intellectuals she was extremely critical of the grassroots cadres. She herself had had very little in the way of governance responsibilities and when she saw these local cadres who occasionally cursed the peasants or maybe not so occasionally and sometimes beat the peasants and sometimes took from them and so forth, she reacted to it with tremendous self-righteousness. And this as the Party historian at East China Normal University, Wang Haiguan, has written about this. The fact that when intellectuals are sent down to the Chinese countryside they often, in his view, really overreact to the abuses of local power that they witness because they’re very unfamiliar with the way in which village politics actually work in China. So Wang Guangmei was quite upset at what she saw and she was highly critical of the local cadres there in Peach Garden for their infractions, their corruption, and so forth. And she then wrote up her experiences in something that became known as Peach Garden Experience in which she talks about the steps that one goes through in mass mobilization and how important it is to fire up the masses against various abuses that are oppressing them. And essentially what she did in that document was to take the tactics that had been used in land reform against landlords and now apply them to cadres, to members of the Communist Party themselves who were accused of being corrupt. She was actually a scientist. She was the first woman I believe in China to receive an advanced degree in atomic physics and she actually was accepted to Ph.D. programs at both Stanford and the University of Chicago, and almost came to the U.S. for a Ph.D. but instead was persuaded to become a member of the Communist movement and to go up to Yan’an in the war time period. Wang Guangmei in Peach Garden Experience takes her scientist sensibility and analyzes mass mobilization. And it really has a lot of fascinating insights. I mean, she says actually social science is so much tougher than the natural sciences. In the natural sciences you have thermometers that measure people’s temperatures and you can tell whether they’re sick or not, whether they need medicine. In the social sciences you have to just intuit the temperature of the political climate, but figuring out what it is and controlling it so that you whip the masses up into a frenzy, but can also settle them down again when necessary, is essential. So she wrote this document, which her husband edited, and then he sent her basically on a speaking tour all around China where she would lecture six to eight hours at a time about her Peach Garden Experience and the importance of using coercive means if necessary against local cadres in order to deal with the corruption that had crept into the Party. The great irony here then of course is that many of these techniques are then used against her and her husband just a few years later in the Cultural Revolution.

Kaiser: It’s Robespierre on the guillotine, huh?

Elizabeth: But it’s a story I think filled with so much irony because Wang Guangmei came from an elite family in Beijing and Tianjin areas, both sides of her family were quite well off and had a great deal of education and she gave all that up to go and join the Communists in Yan’an. And then there’s this irony of her then writing the book on how to attack people which is used against her and her husband in very brutal fashion, in the Cultural Revolution. And then again after the Cultural Revolution she reinvents herself as a major philanthropist. She takes the furnishings, antiques, and so on that were returned to her, her family heirlooms that were turned to her after the Cultural Revolution. And she takes them, sells them and uses that money to help out indigent women and develops a very successful NGO in the post-Mao period. And so she comes back sort of full circle to this aristocratic elite.

Kaiser: When she writes her memoirs toward the end of her life, does she have a sense of the irony? Does she have a sense that what she had been pushing in those lectures in Peach Garden Experience was just one step away from Red Guard-ism, right?

Elizabeth: No, I don’t think so. I don’t think so. I don’t really get any sense of that irony, and she’s obviously a super smart person and she is somewhat reflective on things, but she I think does not see this as a great irony. I think she sees it as the natural course of a revolution. There’s a certain resignation to it, not as much bitterness as I might have anticipated in reading the memoirs and her interviews with various people. There’s a sense of resignation and there is this sense of inevitability that underlies her view of history and of the world. I mean, Tim was saying that as a historian his view is a view of contingency and that’s certainly a view I share, that at every step in the road, we can make these different choices and then the choices come back to haunt us in all kinds of unexpected and ironic ways. But if you believe fervently in the inevitability of history I don’t think you have quite that same sense of irony. And it doesn’t seem to me to be there in her writing.

Kaiser: Yeah. I mean, Communists are teleological thinkers by definition.

Timothy: Kaiser, I want to turn to a movie star and the chapter on Shangguan Yunzhu.

Kaiser: Yeah, right.

Timothy: Because she wrote one of the chapters that— one of the best, I think, and she is an example of living with a Party, and it’s also the intellectuals that you and I share an interest in but she’s a creative.

Kaiser: Right, a cultural figure.

Timothy: Yeah, a cultural figure. And I think that Zhang Jishun, who’s a wonderful scholar working out of Shanghai and was the— Well, quite openly the party secretary of Eastern Normal University for years, very calming, very open-minded. They brought a beautiful chapter here about experiencing life with the Party in the 1950s. And we’ve been talking about people who were identified with the Party, in the Party, and leading parts of the Party, and of course there were— The other not part of the 60 million people then who were not in the Party who had to live with it. And I think her experience is ups and downs and tragic and yet she’s still trying to find a ways to work with the Party. And I think it’s one of the themes that you and I have seen with Chinese intellectuals is a desire to find a way to work with the institution rather than oppose to established intellectuals, but doesn’t mean they have no agency—

Kaiser: That’s right, that’s right.

Timothy: —No dignity, they don’t. I often call it agency through exegesis. So yes, you cite Mao, but you interpret it. And I bet there’s plenty of citing of Xi Jinping that comes right around to what that intellectual was saying 10 years ago anyway.

Kaiser: Absolutely. Yeah, that chapter is fantastic really all about the vicissitudes of culture work during that really important formative decade. There are so many others that I would love to be able to talk about. We haven’t even really talked about Klaus’s chapter on Zhao Ziyang, or about Julia Lovell’s really, really fascinating one about Abimael Guzman and Sendero Luminoso, The Shining Path. My favorite story, I came back from China in ’89 after Tiananmen and went back to UC Berkeley, there’s this place called Revolution Books. Liz, you remember that place?

Elizabeth: Yeah, yeah, I know that place.

Kaiser: I’ve told this story on the show before, but it’s—

Elizabeth: They would come by at the beginning of every semester to try to get me to order all my textbooks for classes through them.

Kaiser: Ah, Christ. But they were Maoists so it was really funny there was that guy—

Elizabeth: RMP, Revolutionary Marxist Party.

Kaiser: Yeah, yeah. So they had these posters of Guzman, Sendero Luminoso people and they were all about that, but they were trying to make the argument. I mean, that ’89 actually represented a resurgence of enthusiasm for Mao. They had as their proof of that a guy carrying a Mao poster in Tiananmen. And I could see just by the way that fellow was dressed and the funny expression on his face that it was ironic, but in any case. So I asked the guy, “Do you guys support the Khmer Rouge?” And he goes, “Hang on a sec. Barbara, do we support the Khmer Rouge?” I love it. I love that. Anyway, the fantastic book I’m really pleased to have been able to have you both on. One final question for reflection here before we go to our recommendations. The Party claims descent from The May Fourth and given that some of its founding figures were very much part of that movement it’s not a groundless claim. Reading the book the debates of The May Fourth period are still being waged constantly throughout this book. I feel like there’s some new recapitulation of the same themes in almost every chapter. It’s not just Wang Yuanhua and many others, you could even argue that today we’re still seeing a lot of that being fought over. And part of that is that national versus cosmopolitan exigencies. I wonder, the founding intellectuals who are very much of May Fourth, Li Dazhao and Chen Duxiu, they both died long before the Party achieved power. Li died in the White Terror in ’27, and then Chen dies in ’42. But how were these cosmopolitans of the early days? And it was let’s throw in a Sneevliet, Adolf Joffe, Michael Borodin, and all these other Comintern guys, what would they make of the Party today? Would they see it as having achieved a kind of cosmopolitanism or would they see it as, this is the outgrowth of a purely national revolution?

Timothy: Well, there’s an argument running through the Western sinology community about Mao — Nick Knight versus Stuart Schram, was Mao more a Chinese and a nationalist or more cosmopolitan and a Marxist? I’d have to say that The May Fourth, I would guess that The May Fourth figures would be largely unhappy with what they see today. I think they would have been happier probably with Jiang Zemin.

Kaiser: Liz, Jeremy?

Elizabeth: Yeah, I share that view and it relates to my earlier concern that basically the top level of the Party has descended into the apparatchik phase, where you have people who are defending certainly the Chinese sovereignty in a highly nationalistic patriotic fashion, but a fashion that has lost a lot of the freewheeling critical quality of the May Fourth Movement. And so I don’t think that the early intellectuals — obviously they would be delighted at the fact that China’s now second and soon to be first largest economy in the world. They would be delighted that China is no longer in a century of humiliation and has emerged from that, and that clearly was a motivating concern for The May Fourth generation. But The May Fourth generation also I think really was motivated by a desire for freedom, freedom from the restrictions of Confucian patriarchy, freedom for women to express themselves in ways that were not entirely controlled by family and so on. And I think they would be pretty uncomfortable with the straight jacket that the Party in many ways has been trying to impose on people’s intellectual imagination. And its lack of cosmopolitanism in that sense. So I think it would be a very sort of bittersweet view on their part.

Kaiser: Yeah. Jeremy, I guess you win. Your man, Jiang Zemin, sits at the very apex of China’s Communist Party history, it’s the best we’ve ever had.

Timothy: The toad wins!

Kaiser: Long live the toad.

Timothy: One of our favorite photos in the book because there’s a score of photos is Jeremy got us the one of the toad, the great inflatable toad with Jiang Zemin in glasses.

Kaiser: Oh, my God, you got that one. I think we should all start wearing our pants up. Jeremy, Liz, Tim, it’s so wonderful to be able to chat with you about the book. Again, the book is called The Chinese Communist Party: A Century in Ten Lives. It’s edited by Tim Cheek, by Klaus Mühlhahn, and by Hans van de Ven. Pick up a copy if you haven’t already, it is truly excellent.

Let’s move on to recommendations. Before we do that I want to quickly remind listeners that the Sinica Podcast is powered by The China Project and if you liked the work that we’re doing with Sinica and with the other shows in the Sinica Network, show your support by subscribing to The China Project Access, our daily email newsletter put together by Jeremy himself and of course, Lucas, and all the other people on our team. Check it out, check it out, it’s good stuff and it really does help. So, recommendations. Jeremy, it’s been a while, man, what do you got for us?

Jeremy: Okay. Well, first of all I’d like to take this opportunity to apologize to Tim and Klaus and Hans because I think I was probably the worst contributor in terms of blowing deadlines and I really tried their patience, so I humbly and publicly apologize for that. But in terms of recommendations, something that I’ve just got hold of based on a book review, and I’ve just started reading it. It’s an illustrated book by a writer and illustrator named Ben Katchor, called The Dairy Restaurant. And I found this thing via, I think somebody’s tweet and read this New York Times review of it. And the tweet, who I apologize, I don’t remember who came up with it, said it was maybe the most Jewish New York story ever. And it’s about Leon Trotsky who spent a little bit of time in New York City in 1917. And he was a vegetarian and kosher, I think, but anyway, he ate most of his meals in Jewish dairy restaurants in New York. And one of his favorites was in the Bronx called The Triangle Dairy. So this book is a graphic history of these things. And in the book Katchor notes about Trotsky that he “refused to tip considering it’s an insult the dignity of the waiters and the waiters retaliated with poor service, accidental spillings of hot soup and insults.” Anyway, that’s my recommendation. The Dairy Restaurant.

Kaiser: Trotsky. God. He deserved the ice pick, not tipping. All right, Liz, what do you have for us?

Elizabeth: Can I give you two recommendations?

Kaiser: Absolutely. You’re absolutely welcome to.

Elizabeth: Okay. And I’ll show you how boring I am because both of those recommendations actually are about China, but I think they really go wonderfully well with the book that we’ve been talking about today because the book we’ve been talking about today, they really humanize rather than demonize China. And one is a book that’s come out recently written by Cheng Li of Brookings and is entitled Middle Class Shanghai. And what’s really wonderful about the book is the way in which Cheng talks about avant-garde art and all kinds of trends in Shanghai that are not terribly well-known outside of the city and really shows you really just what a vibrant place it is. And despite our image of China’s being increasingly drab and controlled by the Communist Party, that there is in fact a tremendous amount going on within the city’s culture. I really think it’s a great book for people who would like to understand a little more about perhaps the most dynamic and certainly the most cosmopolitan city in China. And the other is a book by one of the chapter authors of the book we’ve been talking about, and that is Yang Guobin. And like Cheng in Middle Class Shanghai, Guobin in his book which actually hasn’t come out yet but will come out very soon talks about a city, in his case the city is Wuhan. And I think the title is Wuhan Under Lockdown. It’s the story of Wuhan after COVID-19 hit. And although Guobin himself was not there he basically harvested all of the social media postings, the lockdown down diaries by dozens of people in Wuhan. And it’s a really moving story about the panic, the fear, the concern that people had in Wuhan, but also their heroism to some extent and their sense of community and the sense that although they were giving up their freedom under lockdown they felt they were doing this to keep other people safe. And I think it’s really, it’s a very, as I said, moving story of what this was like in the city where initially in our newspaper accounts in the U.S. this Wuhan lockdown was seen simply as a kind of top-down authoritarian control. Only China could do this and what a violation of people’s human rights to have put them through this kind of lockdown then later on of course we realized that is clearly one of the most effective ways of controlling this public health epidemic. And so a Yang Guobin takes you really through the eyes of the people who were going through it and why they cooperated in many cases at considerable personal costs with the demands for the lockdown. I recommend both of those books. Li and Yang are the two authors. Li on Shanghai, Yang on Wuhan, and they’re really very fascinating accounts of what life in two of China’s largest and most vibrant cities is like for ordinary citizens today.

Kaiser: Great, great recommendations. It’s just hard for me to imagine Li Cheng and knowing him and having read his other stuff just writing about the avant-garde art scene and it’s just hard for me to picture the guy doing that.

Elizabeth: It’s more interesting.

Kaiser: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, absolutely. Thanks, Liz, those were great. Tim, what do you got for us?

Timothy: Well, this is my pay on to those who taught me that China could be cool. [Plays Tang Dynasty’s “The Internationale”]

Kaiser: Thank you. You know what? I have the original recording. (Singing).

Timothy: Now, I want that to be my recommendation, Tang Dynasty-

Kaiser: Oh, okay. I mean, I’m thinking about packaging it as an NFT and trying to make a million dollars, but I have the original recording of the demo we did for Guoji Ge which I play on and I did the arrangement for it.

Timothy: Well, then, would you put that one up because I only have the Spotify version.

Kaiser: Okay, okay.

Timothy: I had an LP disc I bought in the mid-’90s and I was like, “Oh my God, heavy metal.” And of course it evoked for me Star-Spangled Banner with Jimmy Hendrix.

Kaiser: Yeah, absolutely. That’s what you’re supposed to, that’s the idea. It’s funny because I just showed that yesterday to my daughter. I showed her on YouTube Hendrix playing the Star-Spangled Banner at Woodstock.

Jeremy: I have to tell you a little story if I may extend the podcast by a minute relevant to this. I haven’t been on many shows recently but one of the ones I did, I think it was a Dan Wang. And.. oh I know! It was a Clubhouse chat, something I was on with Kaiser, and we had a guest on in a similar situation to we have now on this podcast. And the guest said— somebody who I looked at and thought, “Oh, I’m his age.” And then he said of Kaiser, “Yeah. I’ve known about you a long time because my mom was a fan of your band.”

Kaiser: It’s soul-crushing, I get that all the time now. Wow, yeah, it’s depressing. Oh, well, hey, so it goes.

Timothy: If you can put up the link to your original—

Kaiser: Yeah, I’m thinking, I haven’t released it yet. I mean, because it doesn’t exist in the world right now I’m thinking- I haven’t put it out, it’s right here. I mean, I’m holding up this little cassette player. The only place in the world that I know that it exists is on this cassette tape. There’s also Bu yao taobi and Jiupai and Feixiang niao. Those four songs are on this demo tape and they’re really interesting versions of them. The lyrics are different on Bu yao taobi and all others. The Guoji Ge version doesn’t have the Russian choir obviously, and it doesn’t have that second verse that Ding Wu was singing solo, which I think was really inspiring, I’m really glad that we did that. But it’s all of us singing together and it sounds like a mob of drunks singing the Guojige. But, yeah, I guess.

I have to give my recommendation and it’s really boring. I mean, after that but I’m going to do it anyway. I have to recommend the July/August edition of Foreign Affairs which is really focused entirely on China. The two essays in particular. Well, there’s really good ones from our friends, Jude Blanchette, Yuen Yuen Ang, Orville Schell. But the two that I think I really commend are the essays by Wang Jisi, who is the President of the Institute for International Studies at Beida, and Yan Xuetong, who is the Dean of the Institute of International Relations at Tsinghua, so two very, very eminent Chinese scholars. And with different— Usually they’re considered to be, in the case of Yan, he’s fairly hawkish, he’s a liberal hawk. And then Wang Jisi is more of a liberal but they’re very good, they’re very thought-provoking and I think they really need to be read right now in this moment. I’m not sure of the order in which we are going to be releasing podcasts but listeners may have already heard a chat with Tom Pepinsky and Jessica Chen Weiss from Cornell about Foreign Affairs and some of the essays that have been in it because they contributed something that was in Foreign Affairs online and we had talked about that. In any case, Liz and Tim, what a pleasure, and, Jeremy, so great to have you back on. Congratulations on the book, I am sure it’s going to be— It’s already been very, very well-received and I hope that everyone rushes out and buys it. I had asked our listeners to do that a couple of weeks ago in preparation for this, at least to it have read it beforehand and hopefully some of them did. Thank you so much for your time.

Timothy: Well, thank you.

Elizabeth: Thank you very much, Kaiser.

Jeremy: Thanks, Liz. Thanks, Tim. Thanks, Kaiser, yeah.

Kaiser: Great to see you, Jeremy. The Sinica Podcast is powered by The China Project and is a proud part of the Sinica Network. Our show is produced by Kaiser Kuo and Jeremy Goldkorn, with editing help by Jason MacRonald. Drop us an email at sinica@thechinaproject.com. Follow us on Twitter or on Facebook at @supchinanews and make sure to check out all the shows in the Sinica Network. Thanks for listening and we’ll see you next week. Take care.