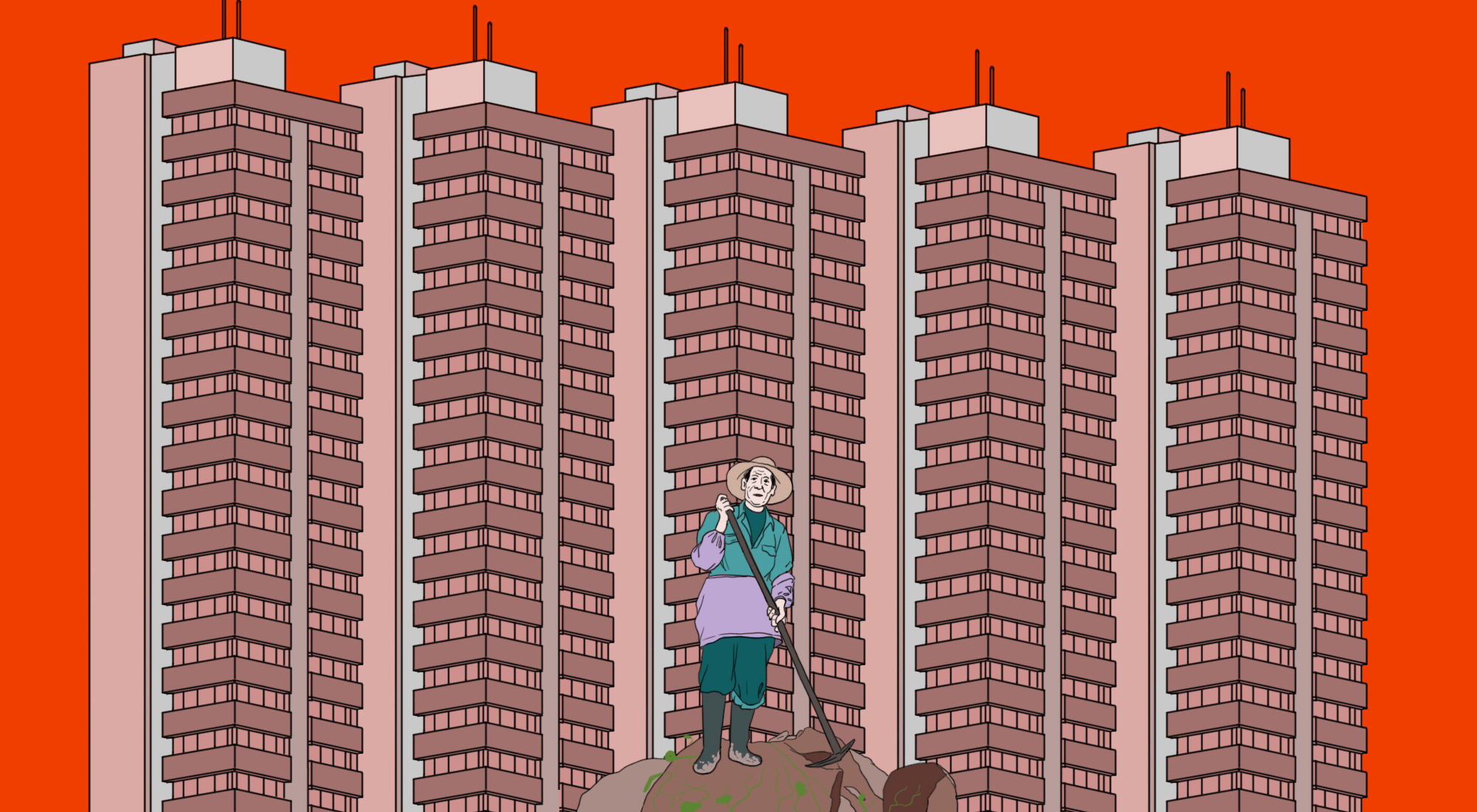

China’s left-behind villages and the people in them

Overburdened grandparents, children who don’t see their parents, workers straining to make a living in unwelcoming cities: Liang Hong's book, "China in One Village" (tr. Emily Goedde), gives a platform for these voices from the countryside.

Sometimes there’s a line in a book that makes you throw it to the side and grab something else. Sometimes it’s the style, sometimes it’s a revealing aside. For example, I enjoyed The Ascent Of Money by Niall Ferguson, but in his The Great Degeneration, as soon as I read, “If young Americans knew what was good for them, they’d all be fans of Paul Ryan,” that was it — all faith destroyed.

I came pretty close to doing similarly when reading the opening pages of China in One Village, by Liang Hong. The author is on the train to back to her family home of Liang village in Rang County, Henan, and gets all ornate:

Once, on this bridge, I saw the most beautiful moon in the whole world […] Its color was a strange, light yellow, like fine Xuan rice paper, and its round elegance was set off by a wisp of cloud across it. Like youthful melancholy, it had a subtlety that was hard to convey.

You know? It’s just a bit too precious. (Apart from anything else, youthful melancholy is anything but subtle.) And that was just after a paragraph which concludes, “To me [the] scenery is both majestic and conducive to the same kinds of solemn reflection.” (I felt much the same about the hills of Scotland, when I was 15 and just brimming with youthful melancholy.)

But I persevered, and I’m very glad that I did. Liang spends a few pages opening her account of her returning to Liang Village and Rang County and establishing their provenance (though Liang “is a made-up name, and characters and relationships described in the book have been altered to protect privacy,” as she notes in the preface). She explains, for instance, that:

Rang County is 2,360 square kilometers or about 900 square miles. It has 28 townships (offices and administrative divisions) and 579 individual administrative villages, with a total of approximately 1,560,000 people and 2,440,000 square mu of arable land.

Such factoids and stats pepper the book, which help to ground it in data and reality. What’s immediately clear is that, for all the economic and infrastructural advances China has made, Rang County has been left behind. The swiftest and largest urbanization in history may have made parts of China relatively wealthy, and its cities huge, but what has been the cost to the rural towns and villages across the nation?

The point of the book is the conversations she has with family members and villagers — from the former schoolmaster (the school now being abandoned) to the County Committee Secretary. In so doing, she cleverly sets herself up as a frame for the other voices and stories to be told, as she describes going from place to place and from person to person, and the memories to which the various locations give rise.

And given that these stories are often earthy and grim, I wonder whether Liang’s florid early manner is there to set up a dialogue between the two styles. Or — because this book was first published in mainland China, in 2010 — perhaps Liang is getting her excuses in early. She loves China, see? It’s only the people that she is interviewing who had bad experiences and are badmouthing the country. Either way, it’s an excellent device, letting her interviewees talk directly to the reader (though she does intervene at times to give the reader greater context). Rather than the adolescent self-importance I feared at the beginning, this is writerly craft and cunning. This is artistry.

For example, when Liang talks to her father, she suggests that he describes his political struggles, “which are, after all, also a part of village history.” There then follows a grim but not surprising story, over seven pages, of his experiences in the Cultural Revolution — being labeled a counter-revolutionary on the flimsiest of pretexts, hiding and then being captured, being “struggled” against (during one session, “a large crowd of students and children threw bricks and tiles at me”) and not being “rehabilitated” until 1978. More than 10 years! Not surprisingly, he is rather embittered.

Or there’s the grim tale of “the Wang boy” who raped and then murdered an 82-year-old grandmother, Mrs. Liu, as she slept in her bed. At the time of the incident, the authorities responded with little more than a shrug:

The Public Security Bureau soon announced that this was an isolated incident, probably perpetrated by a drifter. How were they to know who passed through the village at night, especially by a house so close to the main road? The case was inconclusive, an unsolved mystery […] The Public Security Bureau said they weren’t refusing to solve the case; there just wasn’t enough evidence.

Eventually, after years of police inactivity, DNA is taken from every male villager and the boy is caught. It’s clear Liang blames his childhood issues for his actions:

When he was young, she said, he was never quite right. He never spoke, he was like a closed door. And since he was small, he had lived practically alone. In 1993, when the boy was four or five, his parents went to Xinjiang to farm, and he and his brother went to live with their grandmother. His grandmother died in 1995, and so the boys were entrusted to an aunt.

This is part of a chapter considering “rear-guard” or left-behind children (留守儿童 liúshǒu értóng), kids left with their grandparents while their parents work in the cities. Without an urban household registration (hùkǒu 户口), the children cannot attend local schools; they would have to pay for inferior migrant worker schools. So the children are left with grandparents who struggle to provide for them, the money promised by their parents never quite materializing.

Grandmother Wu tells a desperately sad tale of her grandchild drowning in the river. “He was a handful, monkey-brained, uncontrollable,” she says.

I can still remember his face when he was pulled from the water. Pale as death. Bluish, eyes closed, peaceful. It didn’t look like he struggled. He must have been killed in an instant. I sat down on the sand. I couldn’t get up. The little bastard. He had drowned. I held the child’s body and I cried. What could be done? Old Father in Heaven, take my life for the child’s. I don’t need it.

While all of these are truly affecting, the problem with this kind of book is that while the voices and experiences ring brutally true, there is no discussion of the root causes of the discontent. We are left, as so often in China, to extrapolate backwards, to infer the implied causes of rural decline. There is much that a mainland-published book cannot say. Rural discontent involving the hukou and poor schools are the result of specific Communist Party policies, rather than inherent aspects of rural life.

Liang will not, however, go there. So the reader is left with the impression of various issues without quite understanding what they really are, how they work, and why they are there, which is ultimately frustrating. (Liang does consider the effect of the “New Rural Social Endowment Insurance System for the Elderly” in the afterword, but there’s no real policy discussion beyond that.) Perhaps inevitably, foreign analysts are freer to give a more analytical account of China’s ills. Dexter Roberts’s book The Myth of Chinese Capitalism does precisely this, detailing, for example, the effect of the hukou and the funding issues affecting rural education, and I highly recommend it as a supplement to this book.

It is a bold conceit to think that one village could be a microcosm of China. Decay in one place, such as Dongbei (the northeast) or the central provinces, might be unparalleled economic development in another location, such as the coastal provinces of Guangdong or Jiangsu. What China in One Village does well, however, is to give voice to the unvoiced — the ghosted villages, the overburdened grandparents, the children who don’t see their parents from year-end to year-end, the crippled survivors of the Cultural Revolution, and the workers straining to make a living in cities that do everything to shut them out. China’s great rise might be an astonishing feat, but it has been produced on the backs of the poor and the powerless, at a huge social and psychological cost. Here, the people tell their stories, and make clear that China’s mounting debts are far broader than the financial. Who knows what effect all these issues will have on future generations? It is just unfortunate that Liang Hong can’t thread the implications of their tales into a broader narrative.

For more book reviews, see our Reading China archive.