China claims to have brought hundreds of millions of its citizens out of poverty in recent decades. Bill Bikales, a development economist who worked with the United Nations for 15 years, puts the achievement into perspective.

On this week’s Sinica Podcast, we dove more deeply into one of the diverse topics I mention every week at the top of the show as an example of what The China Project covers: China’s ambitious efforts to eliminate poverty.

My guest was Bill Bikales, a development economist who recently returned to the U.S. after decades working in China and Mongolia. Most recently, he served as lead economist for the UN Resident Coordinator in China.

In June, Bill published a fascinating report titled “Reflections on Poverty Reduction in China,” which is an in-depth assessment of China’s poverty eradication effort. We’ve talked a bit about this subject on this show in the past with guests like Gāo Qín 高琴 at Columbia and Matthew Chitwood, who talked about his work on poverty alleviation in Yunnan for his Fulbright. Bill’s report takes a wider view, looking at poverty alleviation efforts historically and challenging many of the assumptions and nostrums we hear both in uncritical admiration of China’s achievements and in blithe dismissal of China’s claims. It’s a great read that should be required for anyone interested in contemporary China.

Listen to the podcast episode with Bill or read a lightly edited transcript of the podcast below:

Kaiser Kuo: Bill Bikales, welcome to Sinica!

Bill Bikales: Thank you so much, Kaiser. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Kaiser: Well, I’m so glad that we could have you because you’re somebody whom I’ve admired for a very long time. We only really know each other through social media and things like that, but it’s great to finally talk to you, if not face to face, at least on video. So this is your first time on Sinica. So maybe we could start off with a bit of personal background about your career. So give us the quick and dirty version of your China career to date.

Bill: Well, I majored in Chinese studies as an undergraduate in college. That was driven by my interest in classical Chinese literature and philosophy. I just fell in love with it. And that included two years of studies in Taiwan learning the language, studying the classical literature. I went back, I graduated, and had no idea what I was going to do. China had not opened up yet, but then China did. And actually I started — my first career was in China tourism, where in 1979 I led a tour group to China and then ended up spending the next several years, the next five years in one form or another involved in leading, lecturing on cruise boats, too, and organizing tour programs to China. So I got to travel all over the country at the time when not many foreigners had yet visited many of these places that I went to. And I got a very interesting view of China and life in China at that time.

So I did that for a few years, and then decided I wasn’t going to spend the rest of my life doing tourism as a career. I went back to school and ended up studying economics at Harvard with some very good China experts, especially Dwight Perkins, still so wonderful, and am still in touch with Dwight. And then to my surprise, when everything in my career had been pointing me toward work in China, I got an opportunity to go visit and work in Mongolia for a short time. And I ended up spending almost the whole 1990s in Mongolia.

Kaiser: Wow.

Bill: Totally unexpectedly and it was an incredible experience. But it was taking me away from China. We can discuss Mongolia some other time.

Kaiser: Yeah!

Bill: Yeah, I went from there to Ukraine, which had a lot in common with Mongolia, sort of post-Soviet reform situation, then joined the Asian Development Bank in Manila for three years. But this time, by then I was just dying to get back to China and I spent so much time learning. And in 2006, I then moved to Beijing on behalf of the UN and have spent pretty much the whole 15 years since then, until June of this year, in Beijing working for various UN agencies and doing consulting,mostly on China’s social and economic development issues.

Kaiser: Bill, it always augurs well for me when a report on something this big starts off with some broad historical context. What do you think that people should know about the significance of poverty relief in China’s imperial past, and in the Republican period — and how has that shaped the Chinese Communist Party’s priorities?

Bill: I was very struck and I read various analyses by current observers of China of how the Party is using poverty alleviation as a source of legitimacy and so on. And when people make that observation, they tend to be very short term focused, I’d say. “Well, this is the Chinese government eager to prove its legitimacy. It’s what every government likes to do, so they trumpet at this, or they trumpet that.” But I think a lot of that analysis misses just how deeply the claim, even if I don’t accept it as I’m sure we’ll discuss, that China has eradicated poverty, how deeply that claim resonates with Chinese history. I mean, the fact is China has thousands of years, 3000 or more years of recorded history. And it is absolutely correct that the effort to eliminate or to control, not eliminate, to control poverty, to reduce it, especially hunger and famine, which was its most important manifestation throughout history has been a theme throughout Chinese history. And to stand up now, as Xi Jinping did and say, “A history of China is a history of a struggle against hunger and against poverty. And now we have won that battle.” I mean, that does resonate so deeply. And he quoted Qu Yuan — the Warring States poet, and he quoted Du Fu, and he quoted Sun Yat-sen. And that’s absolutely right to do that. So again, I will discuss why I don’t think the claim that China has eradicated poverty is correct. But no matter what, the tremendous progress that has been made certainly should be seen in the perspective of those thousands of years of history. And as I point out in the paper, it’s a history that continued right up until 1949, and I respect that.

Kaiser: Absolutely.

Bill: There were many bad famines in the 19th century. There were terrible famines. And during the Republican era as well.

Kaiser: So Bill, you describe the Chinese government as having a “static view of poverty” — that is, at one point the government identified a group of poor people, and then, at another point in time, those same individuals were re-labeled as having escaped poverty. In your mind, why is this view of poverty incorrect?

Bill: Global experience with poverty alleviation has found repeatedly, in country after country, time after time, that solving a poverty problem is not simply a matter of dealing with the people who are poor at any one moment in time, but it’s also creating systems, institutions, programs that will prevent other people from falling back. Because poverty is not static, it’s dynamic. You’re not “poor” or “not poor.” You can’t just divide the country. There are people who are near poverty. There are people who think they’re doing fine, who encounter some shock — it can be a death, illness, loss of employment, a natural disaster — and suddenly are thrown into poverty. This is what happens all over the world. And of course, China is no exception from that. So the static issue came up specifically with the most recent campaign to eradicate poverty, where it was defined in a static way.

Kaiser: The 2013 campaign, which we will get to, which will be a major focus. But it’s interesting to me that you took your first trip to China as you said in your self-introduction in 1979. That’s shortly after the third plenum of the 11th Party Congress in December of ’78, which incidentally is used constantly by the Chinese leadership as a baseline whenever it makes claims about poverty alleviation. I should add that it’s not just the Chinese Communist Party leadership that does this, a lot of us do. A lot of us implicitly look at ’78 as a baseline. And I mean, I do it constantly myself. There are though a lot of implicit assumptions in choosing this as a baseline. And maybe we should unpack some of those. I think your report does a really great job in spelling them out. It says a lot about how the postmodern leadership up to and including Xi Jinping thinks about the Mao years, right?

Bill: Yes, that’s absolutely right. When I first visited China in 1979, here’s what I saw: I saw a country that clearly was a poor country. There was no question of that. And we went to rural areas and we visited people’s communes in rural areas, not the poorest, poorest areas. But I went to Tibet in 1981, including through rural areas again in the tourism where clearly poverty rates were high. I mean, there were a lot of poor people, but at the same time China was incredibly impressive already. You could see, even the tourism organization: the fact that they could meet us when we arrived crossing the train from Hong Kong to what then — from Kowloon to what, then became Shenzhen later. But that was not even a dream in anybody’s minds at that time. Someone met us there and said, “Here’s your itinerary. We’re going to fly to Xi’an, and then we’re going to take the train to Lanzhou, and then we’re going to come back and go to Baotou and inner Mongolia.” And everywhere we arrived, someone met us and took us to the hotel, the local guides. And it was incredibly — there was a government administration. There was a bureaucracy in place that was an extremely important condition for everything that was going to come after that. So poverty — but at the same time, it was already a very impressive country in many ways. Believe me, I did a little tourism work in Africa and other countries. And you did not have the same experience traveling in other countries on the surface, when you look at just a GDP per capita of we’re at the same point as China. China was far more advanced in some very fundamental ways.

Kaiser: So just that tourism infrastructure — that human tourism infrastructure you’re talking about — is a manifestation of state capacity then?

Bill: Correct.

Kaiser: Very interesting. So I mean, I think that we should talk about what poverty looked like in China during the Mao years. I mean, we’ve just begun this conversation, but I think it’s important to point out, you take issue with those who simply look at other countries in ’78, say. And only compare income poverty instead of looking at, as I think one ought to look at, these other measures, state capacity like you just talked about, education or literacy, life expectancy, child mortality, and taking all of this into account. And understanding that there isn’t a common metric you can squash all that down into and say X units of infant mortality equals… of course not. But could you give us a more realistic picture of where China really was, developmentally, by the late 1970s? Is there a good way to talk about it in terms of how it compared to other countries? Because it’s significantly lower in income poverty. It was like the eighth poorest country in the world or something like that, only measured by income but yeah, very high in terms of literacy, and impressively high in terms of life expectancy.

Bill: Right. Yes, there’s no one metric that can be used to compare. There later on, the UN developed what they call the human development index, which Amartya Sen helped to design. And the whole purpose of that was to say, income is not the ultimate goal. Income is a tool to use to have a better life, to have the capacity to do more things. But income is not the only tool: you need education, you need good health. So they developed this index. And there’s no way to compare China’s human development index at that time with other countries. No one was doing the calculations. But I did try some in the paper simply with that chart showing China’s development course along a range of key indicators and comparing with other countries. And the results are striking.

So for example, how would you — Indonesia at that time had a considerably higher GDP per capita than China, more than double. But China’s life expectancy, China’s secondary school enrollment rates are both much higher than Indonesia’s countries whose GDP per capita were comparable then. China, as you say, was the eighth poorest country in the world. And measured by that indicator were countries whose life expectancy was around 40, and China was already 66. I mean, these countries were really in terrible shape, which China absolutely was not.

So the main point is, you do need to look at all of these indicators together. You can’t simply look at income. And that’s also due to the fact that Mao policies, more and more, especially during the Cultural Revolution years, were almost designed to suppress income. You were supposed to be doing great things out of passion for socialism for Mao himself, for the country, not because you wanted to gain materially from it. And the result of that and of several other specific policies was that rural incomes especially were extremely low.

Kaiser: That’s right. So when the Chinese Communist Party leadership uses ’78 as a baseline, what is it saying about their posture toward Mao, toward the mixed legacy of accomplishment and disaster of the Mao years?

Bill: Their message about those years is really deeply contradictory right now. There’s an internal contradiction. On the one hand, they’re trying to paint a more positive picture of Mao’s years. They describe it as the years of building the foundation for future development. That can be accurate for parts of what Mao did in the ways I describe. They describe it as a path that took twists and turns along the way, which is a gentle way to refer to the great famine that followed, the Great Leap Forward, I suppose. But at the same time, when they say those nice things about it, but they still — when they talk about the great achievements and poverty reduction, they don’t say, “Since 1949, here’s what China has done with poverty.” They say, “Since 1978,” so right after Mao’s death. Implicitly, they’re being very critical of Mao. They’re saying, “Until Mao was gone, and until Deng’s reform and opening up years, China was a mind-bogglingly poor country, 97% of the rural population were poor.”

Kaiser: Right. They are wrestling with the same continuity versus change dilemma that all of us looking at China are. I mean, this is one of the big shibboleths for me when I talk to people and ask them about what they believe the Chinese Communist Party to be, is it the party of Mao or was there a fundamental change after Deng? I mean, because when you look at it, when it’s so different in not only its foreign policy orientation, not only in its basic economic foundation, but also in its very composition, right? I mean, it’s such a different party, and yet at the same time beyond just the need to hold onto the load bearing walls of Mao that you couldn’t do a de-Stalin-ization, right? I mean, it would’ve brought the building down, but beyond that even I think there’s still a lot that they will sole hold up and evaluate in a positive light

Bill: I agree. That’s very well described, but at the same time we do need to acknowledge, if you do want to measure poverty alleviation, poverty reduction starting from 1978, you simply as a matter of intellectual honesty, and as a matter of trying to truly understand what happened and what it’s lessons are for anyone else, you have to ask the question, “Well, why were there so many poor people in China in 1978?”

Kaiser: That’s right.

Bill: And that’s also relevant because there’s some controversy about how much credit Deng Xiaoping and the reforms should receive for what was done in reducing poverty when in the first two decades at least, a lot of that was simply correcting mistakes that Mao had made. It was simply abolishing failed policies and letting much more common sense policies like letting farmers grow what they want to grow, let them sell for the best price they can get, let people move from rural areas to urban areas, of course with some restrictions still in China in order to find better jobs and better income.

Kaiser: So you’ve just brought up two topics that I want to get to. One of them is on the hukou system itself. The other is about this business of when is a more reasonable baseline. So I mean, at what point, or it just no longer a matter of just reversing the bad policies that Mao put in place? That very, very low fruit if you will. And because I think that that comes into play anytime you hear somebody say, “Lifted X hundred million people out of poverty.” That’s a problematic thing. But before we get to that, I do want to ask you a little bit more about poverty in the late 1970s. There was a comment from a World Bank economist that came up in a podcast that I taped with Isabella Weber very recently, talking about how sure, yeah there was poverty in China, but it wasn’t the kind that didn’t allow you to sleep in your hotel at night, and implicitly that he was talking about India or other countries where there was just more in your face poverty.

There’s a lot of critique in your report about the hukou system. I think we’ll go ahead and get right to that. I’m sure a lot of our listeners are familiar with that. And there’s no question that any internal passport system that exists — one, you know, that sets up a whole class of citizenry as a second class essentially — it’s a grotesque violation of human rights. I think few people would dispute that. And yet I’ve heard a lot of people defend the hukou system as a necessary evil. The kind of thing that prevented truly awful suppurating ulcerous slums from forming in Chinese cities the way that they did in Kolkata or in Lagos. Can you talk about that at all? I mean, the mixed blessings — or maybe they aren’t mixed at all — of the hukou system?

Bill: I think it would be safe to say that the hukou system did play a positive role for some time in preventing a massive flow and the creation of the shanty towns and huge slum areas around Chinese urban areas that might have resulted if there had been no controls in place. But I also feel it’s a policy that has been obsolete already for at least 15 or 20 years. And there is at some point, you just need to just bite the bullet and abolish it. There’s simply no justification for it at this point. And specifically from the point of view of poverty there, I don’t see how — well, I’ve expressed myself strongly. To me, it seems quite clear that it’s an obstacle to poverty reduction in the future. Now, China still has 500 million rural residents, not hukou rural residents. And there simply isn’t enough to do to earn income in rural areas in China to support that larger population. So real urbanization, not just reclassifying areas, not trying to build new cities to move people to and say, “Now you were rural, now you’re urban.” But actually allowing people freedom to pursue opportunities where the opportunities actually exist. That has to be a major part of the future poverty reduction agenda in China.

Kaiser: And to what extent is that being discussed now? I mean, every few years you hear about serious proposals for pretty far reaching hukou reform, and they never seem to really get anywhere. During the last 10 years, during this time that Xi Jinping has been in office, has that been something still under discussion?

Bill: Under discussion, but I see no indication that major reforms are in the works, which is understandable as simply as a matter of political economy. Abolition of the hukou system is resisted fiercely by very powerful interest groups. And now I’m not talking about tiny groups of wealthy whatever. I’m talking about the whole urban middle-class. I’m talking about urban governments who would have to provide education and healthcare and other services to a lot more people than they do now. They’ve had it easy under the hukou system. They could attract these people, they could benefit from their labor. These are the people who staff the restaurants, who build the roads, who build the buildings in most cases. I mean, but they never had to provide them with education and healthcare and the rest. And believe me, you’ve had shows discussing the super competitiveness of the Chinese education system in the urban areas where everyone is trying to send their kids after school to a piano teacher and a physics teacher and a math tutor. They’re so concerned with that urban group of urban hukou middle-class people. They’re not eager to have rural folks kids coming in and joining the schools and getting a share of the government resources. So it’s a tough political economy problem, but from the point of view of justice and human rights as you’ve described, and from the point of view of reducing poverty sustainably, it has to happen.

Kaiser: But don’t demographic trends right now point toward maybe more urgency of hukou reform or make it actually maybe something more palatable, even desirable by even some of these urban governments? I mean, we had Cai Yong, a demographer on the show not too long ago talk about the 2020 census and a lot of the demographic changes that are plaguing China in many ways. Aren’t these making it a desirable thing to bring in more of the rural workforce into the cities? Which is to fill these jobs and to —

Bill: Absolutely. And in another way too, and that is what China needs now is better educated workers as income rises. And the best way to provide better education for young people in rural areas, for children and adolescents in rural areas, is not only to invest in improving the schools there, that has to be done as well, but it’s to allow them to move to cities with their parents who’ve migrated, or and have access to already existing good education systems in the cities. Now, China doesn’t have time to waste because of those demographic problems you’ve mentioned. And because they’re trying to build a whole new technology-based economy, you need people who are able to find productive jobs in this new economy. And they’re not going to get it from the education that’s currently being provided in most rural parts of China, not all, but in most. And the simplest thing, let them migrate. This is the global experience. The main reason why people migrate around the world — this has been found in many studies — is not to find better income, but it’s to find better education for their kids. This is a global thing.

Kaiser: That’s why we migrated to the United States. So Bill, among people who work on China as I said earlier, you often hear this phrase, “China lifted X hundred million people out of poverty,” and you see a lot of eye rolls and you hear a lot of objections to that. And you’ll hear figures as high as 850 million, which actually the World Bank used. But many people and myself included have tended to avoid the phrase. I don’t use it in it. But most people dislike it because they think it gives too much credit to the party state. They often offer in place something that I actually — I confess I find equally objectionable — this idea that the state only had to get out of the way. And yeah, I’ve actually said something to that effect before. And may God forgive me for spouting such neo-liberal nonsense ever. But your approach is different. I mean, I think it’s — I really like it. You try to establish the point at which the reversal of bad Maoist policies alone is no longer the major driver of increases in rural income, at which point government policy, government poverty alleviation efforts, proactive efforts, coupled with broader economic growth become more important as the drivers. And you are unequivocal of the idea that since 2013, when Xi’s push began this — that you describe it as “no-holds-barred” and “top-down” targeted push to eradicate poverty — that you can use it. You can say some one hundred million people were lifted out of poverty. Can you talk about how you determined this point at which Mao’s policies were no longer the major drag? And does that point maybe make more sense to you as a better baseline for measuring the success of subsequent poverty alleviation efforts?

Bill: That’s a very interesting thought. Yes, I tend to see Hu Jintao, who people don’t talk much about Hu Jintao anymore.

Kaiser: I love him personally.

Bill: Yeah. Well, I think he — under Hu Jintao, and this was a different time from the current one. So it’s hard to say, “This is Hu Jintao personally, and this is real collective leadership.” And he was a very low profile type of leader. But under Hu Jintao, it’s clear when you look at the policy changes, it was the Party recognizing that growth alone was providing the vast majority of benefits by then to the urban coastal regions that we were all seeing. Even people who haven’t been to China have seen pictures of the skylines and the —

Kaiser: High speed rails.

Bill: High speed rails and so on. So under Hu Jintao, there was a very strong push to redirect some, and a larger portion of government resources towards rural development, towards the rural population. So I mean, until Hu Jintao, rural education, things changed so fast in China that you can forget these things until Hu Jintao. So less than 20 years ago, rural education was still not free. It was supposedly compulsory, but even poor rural households sometimes they could get some benefits, but they had to pay for education, for elementary school, for primary school education —

Kaiser: They were still paying agriculture tax.

Bill: They were still paying the agricultural tax. There was no rural medical insurance. There was no rural pension system. All of these things, all of the — and again, this goes back to the Deng reforms. I mean, when the people’s commune system was torn down under Deng, it also meant that the institutions that had been tasked with providing public services in rural areas were also gone. And it took a long time to come up with some replacement. And Hu Jintao was the one who saw that need most clearly and paid the most attention to it. It had been acknowledged before that, but he made some big changes under, remember the phrase, “the new socialist countries.”

Kaiser: That’s right.

Bill: That was a big deal because at that point, the trend was very much in the opposite direction. Rural areas were falling further and further behind. So that started it. But of course, under Hu Jintao, China joined the WTO. I mean, just before him,but the impact of joining the WTO was felt under Hu Jintao. That was providing much greater benefits to the coastal urban areas and much fewer benefits to the interior rural areas. And he started to address that, but Xi Jinping then took that to a whole new level. So for Xi Jinping, I give him a lot of credit for this. Even though again, I disagree with some of the claims that have been made, he identified rural development and rural poverty eradication as the key criteria that he was going to use to assess whether China had really achieved the Xiaokang, the society goal that he wanted to achieve by 2020. And that was remarkable. But before that everyone had focused on GDP, GDP, GDP and said, “Well, it has to double and double again and double again.” And so on, which of course that was always there too. But he said, “No, this is for it to really achieve Xiaokang in this moderately prosperous society, we also need to look at the poorest ones in the country.” And so he launched a campaign and this was definitely policy driven. And this was definitely the party lifting people out of poverty, because this is again, they sent work teams into all of these poor villages that had been identified. They assigned for two to three year stretches for people from urban areas to go work there and design, implement, and monitor his poverty reduction programs in these poor areas.

Kaiser: Dibao.

Bill: Dibao was actually the smallest piece of it. It was finding them employment, it was agricultural improvements, it was building more infrastructure, it was — they had this, what I call it five prong approach, so wu ge yi pi. And it included education, infrastructure, environmental compensation, health, and some social assistance only for the ones who weren’t able to support themselves when given the opportunity. So this was top-down. This was definitely the government lifting people out.

Kaiser: Let’s go back a little bit before that and talk about the era of low hanging fruit when it was just about reversing Mao’s bad policies. At what point do you think that was over? I think you proposed 1986 as the year that you feel like all the easy squeeze was done.

Bill: Yes. The easiest squeeze was done by then. And absolutely, the growth in rural per capita incomes until 1985 was unbelievable. It was about 16% per year in real terms after taking out inflation. They had a poverty line. Their first official national poverty line was set in 1985, but they were able to go back and look, and poverty was reduced by more than half in those first few years according to the then poverty line. That income increase took place primarily simply by giving farmers the freedom to grow what they wanted and sell it to whom they wanted for the best price they could get within limits. There wasn’t a “big bang” as your discussion with Isabella Weber touched on. It wasn’t a big bang of just totally abolishing the grain procurement system that existed, the grain procurement to make sure urban people still got it was important. But gradually they relaxed and they allowed much more freedom. And that was reflected in this big surge in rural incomes, but that had stopped by 1986. And at that point, the government established their first national poverty alleviation agency, the Leading Group on Poverty Alleviation and Development. And they started national poverty alleviation programs, which didn’t work so well all the time. This was the big drive and the Chinese economy was still FDI-driven growth and urban-based growth. So it was a challenge, but they started to grapple with the problem. Then I wouldn’t say that at that point all the benefits from reversing Mao’s policies had already been gained. That continued for some time still, but the direct benefits from rural liberalization had pretty much slowed down quite a bit by then.

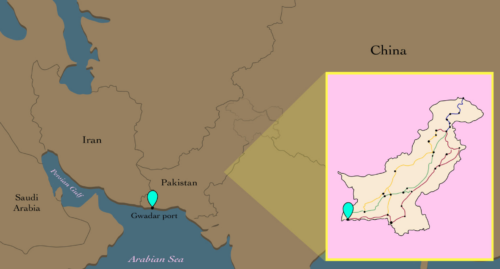

Kaiser: Yeah. So let’s talk about Xi’s campaign. This precise, targeted poverty alleviation and his eradication of extreme income poverty campaign. So before Xi actually came into office, this leading group that you just described that was formed in the mid-1980s had actually raised the poverty threshold to I think it was 2300 RMB in 2010 RMB value. But at that point, it was actually above the absolute poverty line that the World Bank uses. So by the time that Xi came into office, how many people roughly were in extreme poverty? And just as importantly, where geographically were they? What was the reason why they were still in poverty?

Bill: There were about 90 million poor people at that point when they raised the line, which is a good thing to do. China had grown so much. The understanding of what it meant to be poor was changing along with that growth. So there were about 90 million people under the new line that was set then. And they were primarily in the Western and central regions. There were still some in the east, but they were most concentrated and more geographically remote and topologically challenging areas such as Tibet, such as Yunnan. Some of the more remote, rural, mountainous areas, Xinjiang, Xinhai. But of course, there was quite a bit of poverty still in some of the central provinces as well, such as Henan and Shanxi and Shenxi.

This is one of the interesting things about the progress that was made after that in reducing poverty. Basically, the lower the poverty rate got, the smaller the number of remaining poor became, the tougher it was to solve their problems because these were the really tough ones. There’s one area in Sichuan, Liangshan, which is famous. Yes, the Yi minority area which is famous for being just an impossible nut to crack in terms of poverty alleviation. I mean, people were living on mountains and had to travel long distances just to get to anything, a school, a clinic, any work.

Kaiser: So I think you’re very fair in your assessment of the successes under Xi, at the same time of course, you dispute the claims of total poverty eradication and you make that very clear as well, the reasons why you dispute that. The question though that I have is about the durability of poverty alleviation. This is something that we flipped at earlier when we talked about how they have this static view, is that something that’s changing? Are they now recognizing that poverty recidivism and that these at-risk populations, people who with one jolt will send back into poverty are a real big problem. And what is in this next phase, now that the 2020 goal has extensively been met? What are they moving on to next? What is next for them?

Bill: I’m concerned about that problem. And I don’t think the answer is clear yet. They certainly expressed concern about it. They talk about recidivism that — and there’s this phrase which I find very interesting, and that is they talk a lot about fan pin, this people falling back into poverty. But that’s not the same issue that I’m most concerned about. Fan pin is serious but again, it suggests that you’re still talking about a limited group of people. The people who were poor before and that you’ve now lifted out and you want to make sure they don’t fall back in, but at the end of the day, eradicating poverty requires universal social protection programs. At the end of the day, eradicating poverty, if it’s to be a meaningful, sustainable concept, doesn’t simply mean that at one point in time, you have nobody who’s poor. If that’s all it was, it would be easy, you just give out a lot of money 10 minutes earlier, and now nobody is poor.

I mean, at the end of the day, you need universal social protection systems that work well, that respond quickly. That’s a big challenge, but that is the key. And I don’t think China’s there yet. And in my paper, I quote the very recent IMF, the most recent IMF article IV report on China’s economic situation. And the IMF, I was stunned actually, they were very outspoken. They called China’s social protection systems woefully inadequate.

Kaiser: Right.

Bill: And the problem is again, it’s this patchwork of systems. You have urban health insurance, and then you have medical health insurance. You have unemployment insurance that covers people who work for formal sector businesses. But if you’re a migrant worker working in a restaurant, or a Meituan food delivery driver and you, for whatever reason, lose your employment and your income, you’re not eligible to receive unemployment insurance. There are all the basic pillars, including pensions for China’s growing number of older people, a lot of whom live in rural areas. And the pension system is totally a patchwork. There’s a good pension system for people who work for the formal sector or for the state enterprises or offices. And then there’s a residence-based system which has an urban program and a rural program. So all of this, that’s the key. If you really wanted to make it sustainable in the future, the only real way to do it is systems like that.

Kaiser: So I mean, that’s obviously a massive challenge I think for any state, but China I mean, seems like it, at least historically, has shown a willingness to undertake major transformations like that. So maybe not all hope is lost. I think that’s the most compelling part of your report, chapter five, when you lay out that next set of poverty challenges that Beijing ought to be addressing. And you talk about the gaps in the current social protection system. I would really urge everyone to take a good look at this because I think there’s some fantastically good ideas that are laid out there. So what is the path forward toward that? What does it look like? Is this something that’s fiscally achievable in China today? And if so, what is preventing, do you think, China from moving toward the creation of a more comprehensive system, one that really takes into account all the vulnerable groups that you’ve identified. I mean, you wrote about migrant workers, gig or platform workers, the elderly and so forth. It seems like no one would read those recommendations and disagree, but like every government, it faces fiscal challenges, right?

Bill: Right. It’s simply a question of how large a priority the government has prepared to put on social assistance, social protection, as opposed to infrastructure investment and what they see as productive investments. I think in some ways there’s still an old school socialist mentality, the old school socialist as opposed to the new socialist agenda that she has presented and which is very compelling. So the old school one was, production is good, consumption is not so important. Investment is good in infrastructure and investment and building things, space programs, and high-tech factories, nothing was more pleasing than showing a production line producing some wonderful new thing. But social protection seems like something that it’s, “Oh, that’s a Northern European type thing that encourages laziness. And you’re providing funds to parasites.” That’s the old mentality. And I still see the lingering effect of it. Xi, when he laid out this precise poverty alleviation, precisely targeted poverty alleviation program, he said something which was really striking. He said, “The reason why it’s important to be precise, to target exactly the poor, only the poor in the most poor areas and to do it very scientifically, is because if you do anything else, it’s like using a hand grenade to kill fleas.” So that was very clearly rejecting universal social protection as the solution. It was saying, “We want to take an engineering type approach. Let’s identify the poor and let’s engineer a solution to their problems, and then let’s implement and monitor it.” So I don’t know, the fiscal capacity is there if the government is prepared to do it, but it might mean less investment in some areas that they tend to be very proud of as well and I’m not sure —

Kaiser: And the debate has changed so much just in the time since Xi launched his campaign, at least in the west in the country to which they do look, even if they do look askance at Northern European social programs, they’re not ignoring what’s happening in the United States right now, they can’t be. I mean, today I’m reading all sorts of news and licking my chops and waiting for my child tax credit payment. I’ve got two of them, they’re still under 18. Yeah I mean, it’s just in the last — since the pandemic began, I mean, the amount of money the U.S. government has just paid to me directly and I’m hardly poor is pretty astonishing. I mean, I feel like the whole discussion has shifted considerably, and I wouldn’t be surprised if China went along in that regard.

Bill: I hope you’re right. It’s not so clear to me because it’s always you’re choosing, do you want — which is, to you, the greater risk? The risk that you might be providing some support to people like Kaiser who don’t actually need it? Or the risk that you might miss some people who do need it. And if you want to make sure you don’t provide any support to the people who don’t need it, then you’re inevitably going to miss some people who do.

Kaiser: That’s right.

Bill: It remains to be seen. And it’s always… Of course it’s not a binary choice but it’s simply the question of how much investment that IMF article IV report also updated a comparison they’ve made before and that is, they looked at how much China is spending on social services compared to other comparable countries. And it’s China’s spending is still very low in including social protection and social assistance compared to other, what they call, emerging market economies. IMF’s talk or other upper middle income, so it remains to be seen.

Kaiser: Right. Well, the last bit in your report, it was a little frustrating I have to say. I mean, because you look at what lessons, if any, can be gleaned from China’s remarkable poverty reduction achievements, either by developing countries in the global south or even from developed countries with persistent poverty problems. Your report almost makes it sound like just that given the uniqueness of the CCP structure and its reach and the myriad other things that make China almost suis generis, there just aren’t that many lessons that people can easily draw from the Chinese experience. Is that a fair characterization? And do you think that — maybe just talk about your thinking on that question.

Bill: Yeah. That’s a very important question under discussion among development people within the UN and other organizations and certainly with other governments as well. There are many lessons that can be learned at a micro level. So China has done a lot of experimentation with improving agricultural production. And in more difficult areas, China has done an amazing job. And this is truly remarkable for extending key infrastructure networks, electricity, transportation, and the internet now. I mean, to even remote rural areas, this is extraordinary, and this is certainly something that other countries can learn from. It’s when people try to go at the more macro level that I have problems with the simplistic lessons that can be drawn like, “Oh, the key is China has always been committed to reducing poverty and to rural development. And that’s something that other countries should learn from China.” And that’s not so clear to me. There are times when clearly that was not a priority. The importance of economic growth, that’s another one. This is something that Chinese themselves talk about a lot, the importance of growth first, you can’t have poverty reduction without strong growth. Again, it’s not clear. I mean, in China, there have been periods when growth was strong but poverty rates didn’t fall very much. At the very least, it’s not a sufficient condition, it probably helps but it’s not clear.

So these big lessons, and I’m particularly frankly concerned about people trying to draw lessons from Xi’s most recent campaign to eradicate poverty, because there are just simply not many countries that are prepared to do what China did, or have the capacity — or even if they had, it would be prepared to set a binding target. We’re going to move 10 million people in five years from poor areas to somewhere else. I mean, how many countries can set targets like that and can implement them? So then the massive mobilization of human resources and financial resources, I mean, not many countries really would be prepared to do something like that. So the lessons from the most recent campaign are probably the toughest ones to draw at the macro level. At the micro level, tremendously valuable experience has been accrued.

Kaiser: Bill, what’s next for you? Besides of course preparing for a Sinica Podcast with me about Mongolia?

Bill: Well, what’s next for me is turning that paper into a book.

Kaiser: Fantastic!

Bill: Yes. I tried to cover so much ground in one paper. I was given a pretty limited space to work in, but I wanted to talk about the historical context and I wanted very much to make clear the issues about taking 1978 as the base here from which you assess China’s miraculous achievements in poverty reduction. And I wanted to talk about Xi’s campaign. And I wanted to talk about the future and so on, but basically each one of those sections could be a chapter in a book. And I want it to be a book where I do the same thing that I tried very hard to do in this paper, and that is, I like what you say, neither fear nor favor, be balanced, be objective, give credit for the remarkable achievements. At the same time, don’t hesitate to be critical when that seems appropriate.

Kaiser: Well I think you’ve struck such a balance in this report. I think it was really, really well done.

Bill: Thank you.

Kaiser: Again, the report is called “Reflections on Poverty Reduction in China,” soon to be a major book. And if you just Google “Bill Bikales, poverty, China,” you’ll find it right away. We can put a link on the podcast page just in case. Bill, thank you so much for your time. It was really, really fun to talk to you.

Let’s get ready for recommendations, but first let me offer a quick reminder that the Sinica podcast is powered by The China Project. If you like the work we’re doing with Sinica and with the other shows in the Sinica network and you want to show your support, please subscribe to The China Project, access our newsletter. It’s how we pay for the show. And if you do value what we do and you want to see us keep going, you need to pony up. So go to supchina.com/subscribe, sign up for the monthly or the yearly access newsletter and lots of great perks come with that subscription, let me tell you. Anyway, on recommendations, Bill what you got for us?

Bill: I have two recommendations.

Kaiser: Oh fantastic.

Bill: One is a ten-year-old book which I stumbled onto, and it’s a real page turner. And it’s a book called Destiny of the Republic by a woman named Candace Millard. It’s about James Garfield.

Kaiser: Oh wow.

Bill: And it’s about his life. It’s about his death because he was assassinated. But there’s so much in it that resonates with what’s going on today in the U.S. You really understand it’s good to have a realistic picture of American history if you want to be able to assess what’s going on in the U.S today. And one thing which is fascinating, which I had no idea is, she shows conclusively that it was a crazy guy who shot Garfield, but the people who killed him were his doctors.

Kaiser: Oh really?

Bill: Joseph Lister was already around then. Lister had proven conclusively in Europe that disinfecting before surgery, that the basic procedures to avoid causing infections would save so many lives. He had come to the U,S, he’d presented his findings. He had been laughed at and ignored, the way some people laugh at and ignore some of the basic science about COVID.

Kaiser: Wear a mask.

Bill: Yeah. And so the only reason Garfield died was because his doctors treated him so badly. I mean, it’s really quite stunning. Alexander Graham Bell makes a cameo in it as well. It’s quite fascinating. My second recommendation having just moved back to the U.S. is for a car sharing company called Turo, T-U-R-O, which solved a huge problem for me when I came back, because I came back with a lot of luggage and I needed to rent a car, but I didn’t want to rent a car at the airport and drive to my home in it because that would have had to been a huge SUV to carry all my luggage. So instead, I hunted around for the best rental option in my hometown here and —

Kaiser: Which is where?

Bill: — just outside Princeton, New Jersey. And I found Turo, which is the AirBnb of car rentals. So it’s a car sharing program. And I found a very nice retired woman who lives 15 minutes away from where I am now, who had a car available for rental at a much lower rate than the big car rental companies charge. I could just pop over to her house by a taxi and use the car for three weeks while I looked for a real car of my own and then returned it to her home after three weeks. The total cost was much less. The convenience of having someone right nearby was fantastic, so turo.com.

Kaiser: All right. That’s a really, really useful recommendation. I will almost certainly make use of it next time I’m traveling anywhere for an extended time. I hate not having a car and I hate having to rent the car from — Yeah, so fantastic. I actually have one travel-related recommendation as well. Actually, they’re both travel-related. So one is for an audiobook that I just enjoyed while driving up to New York from North Carolina last week. And then I kept — I was just bingeing it on subways and even just while puttering around my brother’s apartment where I’m staying, doing stuff. And it was just great. And I immediately bought the next one in the series. It’s called, The Ill-Made Knight. It’s just this rollicking adventure story. It’s not quite for boys, but the boy in me loved it. It’s about an English man-at-arms who aspires to become a knight and during the time of the Hundred Years War, so he’s at the battle of Potiers with the Black Prince and it’s all the important events of the mid-14th century, it’s just really fascinating. If you’ve read books like A Distant Mirror by Barbara Tuchman, it’s that time, plague and all that stuff. It’s just great. The author is Christian Cameron, who apparently also writes under the name Miles Cameron. This is a recommendation from my fantasy and historical fiction-loving older-brother John, who I saw last week in California. This series is just perfect for a long drive. I highly recommend it. The next one, which I just started, is called The Long Sword. And I’ll drive nice and slowly and wind my way back over a couple of days to enjoy this book. My second recommendation is for the September 11th, the 9/11 Memorial, which unbelievably I had not actually ever visited before this trip. But I went over the weekend with my wife and my children and it was just so well done, it was appropriate. I kept thinking just how marvelously appropriate it was, just from the pools to the actual museum itself, really moving. I mean, just very emotionally moving I think for anyone to see —

Bill: The names.

Kaiser: Oh my God yeah the names. And so yeah, the kid who lived right behind my house when I was growing up, Derek Statkevicus, he worked for Cantor Fitzgerald and died. And I went and found his name and everything but yeah, the names, oh my God. I think it was really brilliant also not to put them in alphabetical order so that you are impacted by walking around and looking through all the names to find the name you’re looking for. It’s genius. I mean, along with the Museum of African-American History in Washington which we visited just a couple of years ago, I am just really blown away by how well this country does these masterful and appropriate commemorations of things, these really great museum experiences. I’ve never seen anything quite like it. These two museums are right up there, but I’m so blown away by the September 11th Museum. It was very, very, very good. And yeah, on that somber note, Bill, what a pleasure it was to talk to you. And really glad I got a chance to do this with you.

Bill: Thank you Kaiser, it was a great pleasure for me too. And I hope it was of interest and will be of interest.

Kaiser: The Sinica Podcast is powered by The China Project and is a proud part of the Sinica network. Our show is produced and edited by me, Kaiser Kuo. Drop us an email at Sinica @thechinaproject.com. Follow us on Twitter or on Facebook at The China Project news and make sure to check out all the shows on the Sinica network. Thanks for listening and we’ll see you next week. Take care.