Chinese history through the prism of its leaders

A review of David Shambaugh's latest book, "China’s Leaders From Mao to Now."

The leadership of authoritarian countries is less constrained than in Western nations; thus, David Shambaugh says, they matter more, and deserve close study. Certainly, the zigzagging of policy in China since the Communist Party took power in 1949 has been larger than probably any country has ever witnessed, taking it from famine to revolutionary frenzy to vast wealth (for some) in just three generations. And without the constraints of an effective governance system to stop them, the personalities of China’s paramount rulers have been perhaps more to the fore than elsewhere. It was notable, for example, how desperately hard the White House strived to make U.S. governance operate in the face of the childish whims and grotesque narcissism of Donald Trump. But while every political leader to some extent remakes government in his or her style, China’s leaders have far larger possibilities in their toolkit — even when denial of them becomes a key part of their governing style, as in the case of Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平.

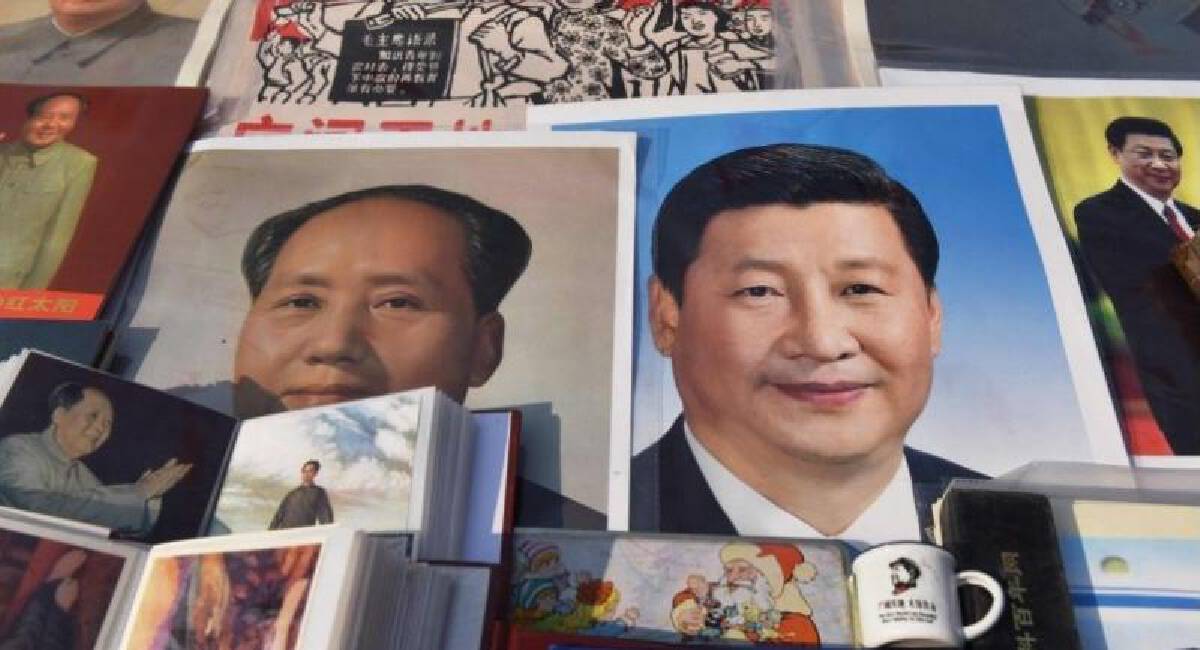

China’s Leaders: From Mao to Now takes the reader through recent Chinese history through the prism of each of its paramount leaders since 1949: Máo Zédōng 毛泽东, Deng, Jiāng Zémín 江泽民, Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛, and Xí Jìnpíng 习近平. He pointedly excludes Huá Guófēng 华国锋 and Zhào Zǐyáng 赵紫阳, neither of whom had ultimate control, despite whatever designation they may have had at the time. These five men, their upbringing, personalities, political careers, and experiences at the very top of Chinese affairs, create a story of contrasts and continuity. Their stories are the stories of modern China.

It is true that authoritarian leaders have an outsized effect on the politics and culture of their nations — after all, in a top-down system, everyone is looking to take their lead from the man (it’s always a man) at the top. Hence why at the moment we have Chinese diplomats in obscure postings competing to see who can conjure the greatest rhetorical violence to buttress their Wolf Diplomacy credentials; or why, in the time of Mao, embassy staff in London in August 1967 engaged in a pitched battle with police to demonstrate their revolutionary zeal.

But what Shambaugh doesn’t mention is that the research possibilities for foreign academics on Chinese officialdom are now vanishingly thin. Books like Ezra Vogel’s great biography on Deng Xiaoping or the incredible trilogy by Frank Dikotter simply could not be written today. The archival access no longer exists. As Shambaugh’s primary sources dry up as we move from Jiang to Hu to Xi, there’s a sense of him telling their stories through newspaper accounts and Xinhua read-outs. Undoubtedly he does a great job of stringing them all together in a cohesive narrative, but without a paper trail and thoughts of in-the-room interviewees (as we now expect in the West, though this is itself a recent innovation: the diaries of Richard Crossman, 1975-77, were the first in the UK to breach the code of Cabinet secrecy), there’s a slight feeling of this being a compilation of secondary sources. Not quite a clippings job — there’s far too much insight for that — but there’s clearly a Great Wall that could not be breached.

Thus, there is no real sense of the administrative manner of any of the leaders, their chairing of committees, their personal relationships, their methods of motivation and management, their control of the governing machine — with the exception of Mao, whose daily life was recorded by his personal doctor. (Mao hated committees, and stopped attending Politburo and Central Committee meetings after 1959, which I find astonishing — but he read assiduously and was a master at intrigues and the Delphic non-answer). There’s also a tendency to look at their young lives and to speculate about the psychological effects, which doesn’t feel particularly rigorous. For anyone familiar with the extraordinarily granular works of Robert Caro on Lyndon Johnson, Seymour Hersh on Nixon, or Peter Hennessy on British post-war governance, this all might be something of a disappointment. But you can only work with what you’ve got, and Shambaugh’s notes demonstrate a deep familiarity with the party’s published materials — though, of course, in an intensely information-retentive organization such as the CPC, what’s published is the merest glimmer of the politics going on behind closed doors.

Shambaugh does not attempt a finely honed study of the five men’s working methodologies, but does attempt a framework by classifying the character of each. These are: Mao (populist tyrant), Deng (pragmatic Leninist), Jiang (bureaucratic politician), Hu (technocratic apparatchik), and Xi (modern emperor). These are solid conceptual bases for each man, and Shambaugh assiduously works to establish the veracity of these designations. Deng’s name might be synonymous with pragmatism, for instance, but the extent to which he spent his leadership rebuilding the party as a governing force might be underappreciated. Jiang likewise strived to build his power base in various sectors, and was a very skillful adapter of others’ programs and policies.

Of the five designations, Hu’s is perhaps the least fair: he had a vision for China that Shambaugh explains was thwarted by the shallow roots of his support, which itself is rather odd given the length of his time as heir-apparent. Hu evidently failed to use this period to develop the various constituencies on which his power would depend:

Notably missing…is anything concerning the military or national security, science and technology, economic reform, anti-corruption, education, the environment, public health, Taiwan or Hong Kong, or relations with specific foreign countries.

Hu aimed for a less divided China, to narrow the divide between the seaboard and the interior, and to make development more sustainable. However, with Jiang retaining influence (having stacked the Politburo before his reluctant retirement) and having failed to develop a broad power base, Hu’s initiatives turned to dust.

Shambaugh also writes interestingly on the conservative turn from about 2008. This he largely attributes to personnel:

Politburo strongman Zeng Qinghong [had] to retire in 2008; internet security czar Zhou Yongkang becoming increasingly powerful; Propaganda Director Liu Yunshan also becoming increasingly powerful and having commandeered the ideology portfolio from Hu; and Chongqing Party secretary Bo Xilai attracting increased national attention.

Perhaps so. But the “sense of malaise” Shambaugh records around the leadership in 2009-10 filtered through to the public and its perception of the party. Those were the days when Chinese social media was astonishingly freewheeling and contempt for the party’s corruption and ineffectiveness was in the air. Chinese politics is often an endless conflict between loosening and tightening, and after close to 30 years of gradual opening up, I don’t think Xi was the only one intending a crackdown on the modest liberties that ordinary Chinese people were starting to enjoy.

The Xi chapter is of course necessarily incomplete. What’s interesting there — besides Xi’s efforts to dismantle Deng’s institutionalization of power — is that a completely different matrix will be needed to assess his paramount leadership, with foreign policy and diplomacy more substantial than any of the other four. Another key area is excerpts of a translation of CCP Central Committee Document 9 from 2013, which establishes the ideological framework for the party’s extreme hostility to any reduction of its monopoly on political power, whether through “constitutionalism,” “universal values,” civil society or “historical nihilism.” This is a fascinating document which may well have as much influence on China as Deng’s Southern Tour, albeit in an entirely different direction.

China’s Leaders: From Mao To Now is not a perfect book. (Apart from anything else, I would have liked more on Jiang’s crackdown on the Falun Gong, which only gets a page or two.) Yet its corralling of the available sources on the five paramount leaders, its readability, its deep understanding of Chinese politics and society, make it a very good book indeed. Perhaps a more comprehensive book could be written in the future. I don’t think it can be now.

For more book reviews, see our Reading China archive.