Why Xinjiang is an internal settler colony

This essay is adapted from Darren Byler’s forthcoming book, Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City, published by Duke University Press (December 2021).

The transformation of the Uyghur-majority lands of Southern Xinjiang known as Alte Sheher, or the Six Cities, came in waves, first in the 1950s when systematic political changes to Uyghur and Kazakh social life began, and then in the 1990s when resource extraction infrastructure, industrial farming, Han settlers, and the Chinese market changed all aspects of Uyghur life.

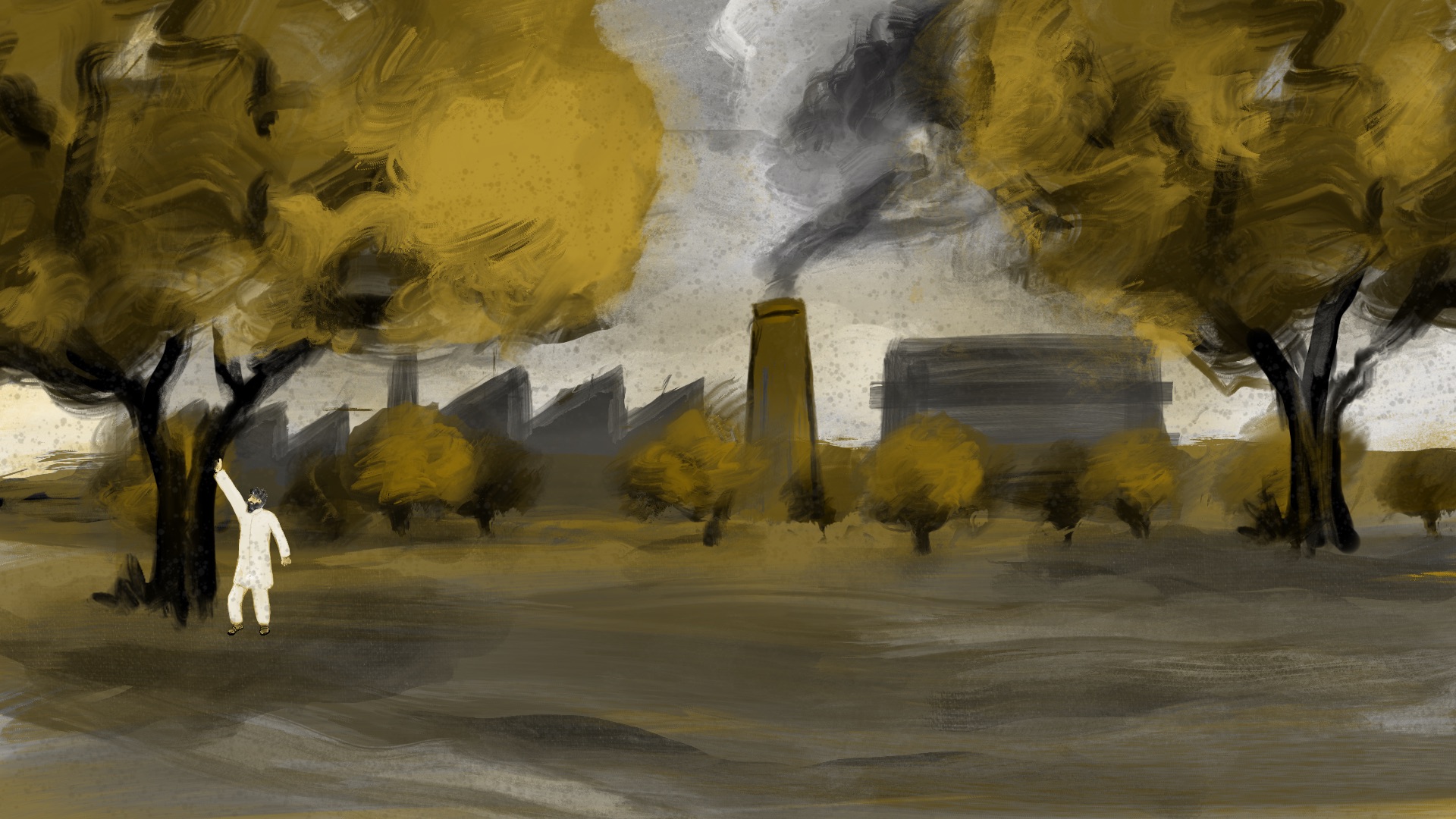

An elderly Uyghur farmer in Khotan I interviewed in 2015 illustrated this process using the lives of trees as an example. He said that, in the Uyghur homeland, there were three generations of trees:

First, there were the trees that still remained from before the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. These trees were quite rare and viewed as sacred.

Then there were trees that were planted in the villages organized as work brigades (大队 dàduì) during the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s. During this period, Uyghur farms were consolidated into communes and farmers were moved from standalone farming homesteads into villages, where most houses were the same height, and for at least some periods of time they shared communal meals. The trees that were planted in these new villages were quite tall in 2015, but many of them had been replaced by a third generation of trees.

These new trees, planted in the 1990s and 2000s, were the “Open Up the Northwest” (西北大开发 xīběi dà kāifā) and “Open Up the West” trees (西部大开发 xībù dà kāifā). The people I interviewed also called them “investment” (Uy: kapital) trees. In many cases, the work brigades, which are still the most common form of rural government in Xinjiang, sold the rights to these young trees to villagers. At a certain point, decades from now, they will be permitted to cut down the trees and enjoy the profits of their lumber.

The old man sighed at this point. “What those people who are buying and selling trees are forgetting is that the trees hold the spirits of our ancestors within them. We have always used wood to build the thresholds of our houses, but we did so out of respect for the trees and as a way of guarding our home from evil spirits. Now that respect is lost.” When Uyghurs begin to treat sacred landscapes like sources of capital — the actual word Uyghurs use to describe “investment trees” — their relationship with the deep history of the land is severed.

In Xinjiang, dispossession is not just about a lack of compensation, it is about a process of illegalizing traditions and turning sacred land into property.

The material transformation of the value of trees in the minds of Uyghur farmers was representative of broader structural adjustments and transformations of Uyghur social reproduction. These broad transformations were signaled first by the consolidation of homesteads into communal villages in the 1950s and 1960s, and then by the arrival of highways and railways in the 1990s and 2000s throughout Southern Xinjiang. This second wave of hard infrastructure transformations targeted oil and natural gas reserves in order to fuel the growing industrial economy in Eastern China.

It is important to emphasize that in a frontier space like Xinjiang, acts of expropriation — legalized land grabs, the takeover of banks and schools, coerced labor, and so on — are not simply a neutral function of state capital in service to the economy. It is not quite the same as state seizure of farmers’ lands in other parts of the country, which is more a function of social inequality and profit maximization. Because they occur on the ancestral lands of Uyghurs and Kazakhs, these processes of dispossession are what establish a relationship of domination over people who are marked as different because of the language, faith, and ethno-racial phenotypes.

In Xinjiang, dispossession is not just about a lack of compensation, it is about a process of illegalizing traditions and turning sacred land into property. Oil and gas pipelines, the railroads, the industrial farms put in motion a new service sector and market that placed settler populations from other parts of China at the center of local politics and economy.

These three elements — material dispossession, institutional domination, and settler occupation — are what established Xinjiang as a contemporary settler colony that was internal to the Chinese state.

Open up the Northwest

In the 1990s, the displacement of Uyghur and Kazakh lifeways became more acute. Many Uyghurs refer to the decade prior, the 1980s, as a Golden Era when possibilities seemed wide open. The relative economic, political, and religious freedom that accompanied the Reform and Opening Period seemed to promise a brighter future. Many Han settlers who had come to the northern part of the region during the Maoist campaigns — corresponding with Stalin’s suggestion to Liú Shǎoqí 刘少奇 that Chinese settlers should “occupy” Xinjiang and prevent the Muslims from being “activated” — returned to their hometowns in Eastern China. But with the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991 and the independence of the Central Asian republics, China’s state authorities were suddenly faced with rising tensions regarding Uyghur desires for greater self-determination. At the same time, the fracturing of the Soviet Union — China’s long-term colonial rival — offered new zones for building Chinese influence. Even more importantly, it created opportunities to access energy resources.

A chief concern among state authorities in the Uyghur region was that the freedoms Uyghurs enjoyed in the 1980s threatened to flower into a full-throated movement for self-determination. As Uyghur trade relationships increased in emerging markets in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, and cultural and religious exchange with Uzbekistan was rekindled, Chinese authorities became increasingly concerned that Uyghurs would begin to demand the autonomy they had been promised in the 1950s. As a result, an underlying goal of the Chinese state’s attempts to control Central Asian markets and buy access to its natural resources turned toward an intentional isolation of Uyghurs from Turkic peoples across the border. At the same time, in June 1992 Chinese leaders announced a new policy position that would turn the Uyghur homeland into a center of trade, capitalist infrastructure, and agricultural development capable of further serving the needs of the national economy.

One of the main emphases in the new proposal was the need to establish Xinjiang as one of China’s primary cotton-producing regions. Given the exponential growth in commodity clothing production in Eastern China in the 1980s, state authorities and market-oriented state-owned textile companies were determined to find a cheap source of domestic cotton to meet the accelerating demand for Chinese-produced t-shirts and jeans around the world. Infrastructure investment in Chinese Central Asia expanded from only 7.3 billion yuan in 1991 to 16.5 billion in 1994. Over the same period, the gross domestic product of the region nearly doubled, reaching a new high of 15.5 billion yuan.

Much of this new investment was spent on infrastructure projects that connected the Uyghur homeland to the Chinese cities to the north. As Qiang Ren and Yuan Xin note, over this time Xinjiang became the fourth largest receiver of Han migrants in the country, ranking just behind Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangdong when it came to new construction workers. By 1995 the Taklamakan Highway had been completed across the desert, connecting the oasis town of Khotan to Ürümchi, cutting travel time in half. By 1999 the railroad had been expanded from Korla to Aqsu and Kashgar, opening the Uyghur heartland to direct Han migration and Chinese commerce. During this time, the capacity of the railways leading from Ürümchi to Eastern China doubled, allowing for a dramatic increase in natural resource and agricultural exports from the Uyghur region to factories in Eastern China.

As infrastructure was built, new settlement policies were also put in place. Like the settler policies from the socialist period, these new projects were intended to both alleviate overcrowding in Eastern China and centralize control over the political frontier. But unlike those earlier population transfers, this new settler movement was driven by capitalist expansion as well.

For the first time, Han settlers in Xinjiang were promised upward mobility through profit in the lucrative natural resource economy and capital investment. Initially, this enterprise — formally labeled “Open Up the Northwest” — was centered around industrial-scale cotton production. State authorities put financial incentives in place to transform steppe and desert areas for water-intensive cotton cultivation by both Uyghur farmers and increasing numbers of Han settlers. They introduced incentive programs for Han farmers to move to Xinjiang to grow and process cotton for use in Chinese factories.

By 1997, the area of cotton production in Xinjiang had doubled relative to the amount of land used in 1990. Most of this expansion occurred in what had been Uyghur lands between Aksu and Kashgar. In less than a decade, Chinese Central Asia had become China’s largest source of domestic cotton, producing 25 percent of all cotton consumed in the nation — a proportion that increased over the following decades. By 2020, 85 percent of Chinese cotton was produced in the Uyghur region.

Expropriation and domination

Yet despite this apparent success, important concerns began to emerge. Chief among these was the way the new shift in production and settlement was affecting the Uyghur population.

Many Han settlers profited from their work in the Xinjiang cotton industry as short-term seasonal workers who received relatively high wages, as settlers who were given subsidized housing and land, and as managers of larger-scale farms. But many of the Uyghurs who were affected by the shift in production did not benefit to the same degree.

Using threats of land seizures and detention — a type of legalized theft or expropriation — local authorities often forced farmers to convert their existing multi-crop farms to cotton in order to meet buyer-imposed quotas. In the same manner, in their capacity as brokers with state enterprise buyers, local officials forced farmers to sell their cotton only to these buyers. These corporations in turn sold the cotton at full market price to factories in Eastern China.

Many Uyghur farmers were pulled into downward spirals of poverty and dependence, while many (though not all) Han settlers continued to benefit from the shifting economic trends (see Tom Cliff’s work for a nuanced account of Han experience of this). Labor exploitation coupled with land seizures gave rise to an intensifying relationship of state domination and occupation, as the need for cheap sources of energy and raw materials increased in the rapidly developing cities of Eastern China.

As the historian James Millward notes, although the economy has grown at exponential rates across China, Uyghur rural incomes have grown at declining rates as people have been pushed into tenant-farming positions. Building on the pioneering work of the Uyghur economist Ilham Tohti, Millward shows that systematic blockage of Uyghurs from lines of credit, business credentialing, and freedom of movement — while incentivizing Han settlement and capital accumulation — has caused economic development in the region to be centered around ethnic affiliation. This has resulted in what anthropologists Ildikó Bellér-Hann and Chris Hann have termed “the great dispossession” of the Uyghurs — an overwhelming threshold movement within the broad sweep of the colonial history of the region.

By the early 2000s, the Uyghur homeland had come to resemble a classic peripheral colony.

For Tohti, the most important factors associated with Uyghur dispossession were “blatant ethnic discrimination in hiring, a rural labor surplus, overconcentration of economic resources in Han Chinese-dominated urban areas, ‘stability maintenance policies’ that restrict population mobility and exacerbate rural unemployment, and severe underinvestment in basic education.” Millward argues that “what Tohti described — without using the word — is a colonial system of settlement and extraction in Xinjiang.”

This process has been fostered by state capital, which subsidized the development of natural resource and industrial agriculture sectors by injecting billions of yuan into the region. As the sociologist Ching Kwan Lee has shown, Chinese state capital often acts as a subsidy in securing long-term economic interests even if they are not immediately profitable. By investing in the Han settlement of Xinjiang, putting settlers to work in natural resource extraction and overseer positions on industrial farming plantations, and fostering a service sector that supported this development, the state was assured of a permanent reserve of domestic energy and raw materials essential to economic growth.

By the early 2000s, the Uyghur homeland had come to resemble a classic peripheral colony. In the context of the nation as a whole, the primary function of the province was to supply the metropoles of Beijing, Shanghai, and the Pearl River Delta to the east with raw resources and industrial supplies. Cotton production continued as it had in the 1990s, but by the early 2000s, industrial tomato production had also been introduced. As of 2020 the region accounted for approximately 35 percent of the world’s tomato exports.

At the same time, as in most peripheral colonies, the vast majority of manufactured products consumed in Xinjiang came from factories in Eastern China. The clothes manufactured using Xinjiang cotton were purchased by consumers in Eastern China at inflated prices. The same was true of the natural gas and oil that began to flow to Eastern China from Xinjiang after the completion of pipeline infrastructure in the early 2000s. In 2014, Uyghur protests against these obvious forms of west-east wealth transfer were officially outlawed as one of 75 signs of religious extremism or violent terrorism.

In the 2000s, the buildout of infrastructure for natural resource extraction that followed behind the new road and rail projects of the mid- to late-1990s again began to shift the center of Xinjiang’s economy. Within a few short years, oil and gas sales came to represent nearly half of the region’s revenues. At the same time, given the push to reduce the nation’s dependence on foreign cotton, oil, and gas — and to accelerate the settler colonization of the Uyghur homeland — the central government continued to provide nearly two-thirds of the region’s budget in the form of state capital investment.

Open Up the West

In the early 2000s, the Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛 administration took the regional project “Open Up the Northwest” to a new level, rebranding it as “Open Up the West.” Now all of peripheral China, including Inner Mongolia and Tibet, became the target of settlement and development projects, though Chinese Central Asia continued to receive a greater number of new settlers relative to other regions.

The “Open Up the Northwest” project had resulted in rapid and sustained economic growth of over 10 percent per year since 1992, so state authorities were eager to take the development projects further, opening new markets and new sites for industrial production. By the early 2000s, the Uyghur homeland had become the country’s fourth largest oil-producing area, with a capacity of 20 million tons per year. Given that the area had proven reserves of petroleum of over 2.5 billion tons and 700 billion cubic meters of natural gas, there is little doubt that the region is thought of as one of China’s primary future sources of energy, even though extracting Xinjiang oil has proven to be logistically difficult. Still, as of 2016, the average cost of oil in the region was approximately $45 per barrel, considerably cheaper than oil produced in the Canadian tar sands.

Between 1990 and 2000, the population of Han settlers grew at twice the rate of the Uyghur population. By the late-2000s, it was almost the same size as the Uyghur population, though many areas in Southern Xinjiang still had a high majority of Uyghurs. As Tom Cliff and Emily Yeh have demonstrated, the development of state capital investments and industrial agriculture export production that accompanied the “Open Up the West” campaign had the effect of rapidly increasing the rate of Han settlement in Uyghur and Tibetan areas. New infrastructure — railroads, pipelines, and real estate — have disproportionately benefited the millions of new Han settlers and produced exponential increases in costs of living and widespread disempowerment of Uyghurs from land and housing.

Uyghur migrants to the city told me that, over this period, the costs of basic staples such as rice, flour, oil, and meat more than doubled. Urban housing prices doubled or tripled, while projects to urbanize the Uyghur countryside placed Uyghurs in new housing complexes that were dependent on regular payments for centralized heat and power. The land-based means of production in small-scale Uyghur mixed-crop farming with small herds of sheep and garden plots were also often enclosed and turned into corporate farming. Underemployment was further exacerbated by the widespread consolidation of Uyghur land into industrial farms and, more recently, restrictions on labor migration. All these public and private economic interventions produced a new kind of Uyghur farmer.

These three elements — material dispossession, institutional domination, and settler occupation — are what established Xinjiang as a contemporary settler colony that was internal to the Chinese state.

One of the primary goals of the state development campaigns were to increase the production of commodity goods — such as rape seed, tomatoes, cotton, and other commodity crops — on an industrial scale. Based on my interviews with farmers and their relatives, within just a few short years, many Uyghur farmers were forced to sign debt-inducing contracts that did not meet their basic living expenses or their seed and farming equipment expenses. Farming itself was turned into a form of tenant farming in which farmers could not decide for themselves what they were to grow, as centralized industrial farming took over their land. Millward notes, “Under the system of the ‘five unifieds,’ plowing, sowing, management, irrigation and harvest were all centralized under county and township control. Uyghur farmers had to buy seeds, fertilizer, pesticide, and plastic film (for water retention) from the local government, which determined the price for these inputs; the government also set prices for the harvest it purchased.”

As the Uyghur scholar Bakhtiyar Tursun, a social scientist based at Xinjiang University, notes in a systematic study of farming economy in the Uyghur heartland of Khotan, Kashgar, and Aksu, rural farmers were nearly always forced to pay a percentage of their profits to work brigades that signed contracts with state and private buyers. As one local official in Khotan Prefecture described it to him, “If a farmer grows 10 acres of wheat, according to the local standards for harvest yield and grain sales price, the farmer should receive an income of 4500–5000 yuan. However, the farmland fee, planting fee, water fee, fertilization fee, management fee, land tax, township and village fund payment, public welfare payments and other expenditures will total around 4000 yuan. After deducting these expenses, the farmer will only receive around 500–1000 yuan.”

As a result, by the mid 2000s, in many counties in Southern Xinjiang, the rights to a high percentage of arable land were owned by a few powerful individuals within local party institutions. This meant, in effect, that the majority of Uyghurs in these counties were living as sharecroppers: their land and work were largely owned by local officials. Many Uyghur farmers, or their children, were forced to look for work either as migrant agricultural workers or small-scale traders and hired hands in local towns or, at times, the big city of Ürümchi.

The shift to re-education

In trying to escape rural dispossession, Uyghur migrants found themselves trapped. As the geographer Sam Tynen argues in a forthcoming essay, as early as 2013, “Xinjiang authorities believed that ethnic minority migrants in Xinjiang needed to be targeted and ‘transformed’ (转变 zhuǎnbiàn) through a range of legal education and training measures.” Drawing on a state report, they show that “Uyghur migrants in the city were seen as a threat to the safety and security of the city and Han populations, and therefore had to be detained and re-educated for their extremist beliefs.”

As the system tightened first around the land — specifically the removal of Uyghurs and Kazakhs from it — and then on their remaining social institutions — the banking system, the education system, the religious system, the health system, and eventually their family and household structure — dispossession, the taking of their material world, was joined by a relationship of domination that threatened their ability to reproduce themselves as a people. This threat to the practice and teaching of their traditions is what calls their future into question.

Even the trees appeared to become the domain of settler society.

In Xinjiang, there is a common saying regarding the ancient poplar trees from the Uyghur oases. It goes roughly like this: “They stand erect for a thousand years, live on for a thousand years after falling, and remain alive after they die for another thousand years.” Because these phrases are plastered on signs and billboards by Chinese tourism companies throughout the region, I assumed that it must be a proverb from Journey to the West or some other historical Chinese text. But when I mentioned this to a Uyghur friend, he laughed.

“This is a Uyghur proverb regarding our most sacred trees,” he told me. “It’s just another thing that they have stolen from us.”