The forbidden dance of the hutuktu

Finding a living god on the Inner Mongolian steppes.

HOOOOOONK!

The machine bellows in the distance.

I am on my motorbike on an Inner Mongolian country road, tracing the footsteps of early-20th century Danish explorer Henning Haslund-Christensen, when I see the monster barreling toward me. What was just a small white dot on the horizon just a few seconds ago is now less than 100 meters away, with steel poles jutting out horizontally on each of its sides, at the height of my neck.

It is getting closer. My arms tremble on the handlebars of my Suzuki GN-125.

HOOOOOONK!

What am I doing out here?

Earlier that day, I had crisscrossed the roads west of Shāngdū 商都 in search of the Temple of Larks, a famous religious site of pilgrimage on the Inner Mongolian steppes. The temple is so-named because larks were the best songbirds on the steppes, and could be sold to bird markets in Beijing, Datong, and Baotou.

I was unable to find it. At a cafe, a hostess suggested I take a “shortcut.” Her recommended road turned out to be a narrow and dusty hell, elevated 10 meters over the never-ending steppes. And now, a construction vehicle of some kind is rolling toward me, its arms extending to both sides of the elevated road.

In my head, the iconic lines Haslund wrote upon visiting the temple flash with grotesque irony:

“We had nothing to fear from the lamas of the monastery or from his nomads, but a possessed gurtum was not a human being, but was the god himself incarnate in a chosen human body.”

HOOOOOONK!

“No man could be responsible for the actions of a possessed gurtum, since during his ecstasy he was a god.”

HOOONNNN…

“A gurtum carries the god’s dangerous weapons, and it might happen that the god’s will was to make away with an objectionable person.”

…NNNNNK!!!

We are locked in a dance. A dance of death on the Mongolian steppes. A sudden movement could cause me to be crushed underneath the great wheels of the machine. But I have nowhere to go: the road falls sharply to dirt below.

The machine is basically on top of me. Adrenaline shoots through my body. I jerk the handlebars of my motorbike to the side. As the machine whizzes by, I throw my head around the side of its steel talons, which miss my head by mere inches.

HOOOOOOOOOOOOONK!!!

“No Mongol could protect us against gurtums, for the people of the steppes could not set themselves against the gods of the steppes.”

In 1927, Haslund undertook a camelback trip from Beijing to Xinjiang as part of something called the Central Asiatic Expedition, headed by the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin, who at that time may have been the most famous explorer in Europe. What Haslund got out of it was the book Men and Gods in Mongolia, published in 1935, a chronicle of three years of expedition as well as the customs of the Torgut Mongols in and around present-day Korla. It was a hit, consumed by audiences in Europe and America. The New York Times called it “a book which dullness never enters.”

I have read many historical on-the-road accounts from China, but Haslund’s struck me as different. In a time when many travelers favored a Tintin-esque tone and leaned heavily into the exoticism of the “Far East,” Haslund’s account was lively and respectful of the people he encountered. He spent most of the 1920s in northern China, becoming fluent in Mongolian and Chinese while setting up an experimental farm close to the Russian border.

One place in particular stuck out to me from Haslund’s accounts: The Temple of Larks, or Bǎilíngmiào 百灵庙.

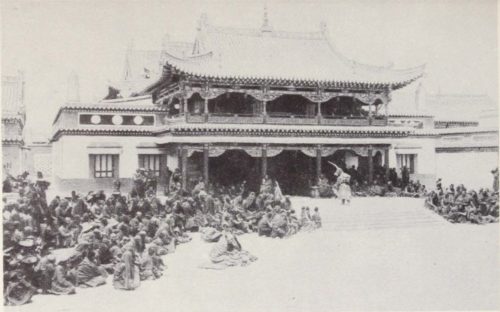

The temple was part of a major expansionist policy by the Qing emperor Kāngxī 康熙 to pacify the people of the steppes. The thinking was that if people could pray at local temples, they would be less tempted to rummage the steppes in search of fights. Bailingmiao became one of the major temples on the pilgrimage route between Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia and Lhasa in Tibet, known throughout the Buddhist world as a place where people would gather each spring during the Maidari, or Festival of the Dancing Demons. The temple was even featured on the bank notes of the short-lived Mengjiang Mongolian state, a puppet regime of the Empire of Japan.

In his book, Haslund pays particular attention in describing the shamanic “gurtum,” dancers who traveled among temple fairs and festivals, performing as the dangerous and vengeful gods incarnated in human form.

In 2019, I set out from Beijing to retrace the steps of the Central Asiatic Expedition through neighboring Hebei province and across the steppes of Inner Mongolia. And I knew that, no matter what it took, I would have to set foot inside the Temple of Larks.

The cafe hostess in Shangdu was right. Near-death encounters aside, this road did indeed lead to the temple. I arrive in the dead of night, pulling up to a gate with statues standing guard on either side. Locked. I find a guesthouse close by to spend the night.

The next morning, the temple gate is still closed. I swing around to a side entrance, where I encounter a young lama, bald and with a small beard underneath his lower lip. He is wearing a blood-red gown lined with golden thread, held in place by five knots — two by his throat and three over his right collar bone. He invites me into an inner chamber, where a handful of young lamas — followers of Tibetan Buddhism — are gathered, the modern occupants of this temple.

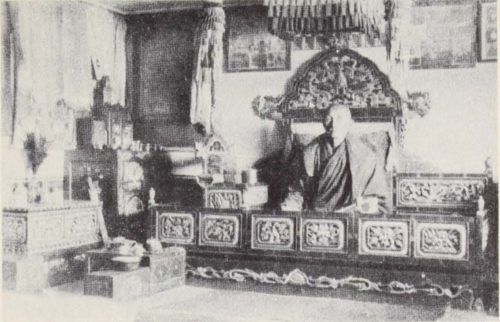

I pull out Haslund’s Men and Gods of Mongolia, and show the young lama a photo from 1927.

“This is your temple, right?” I ask.

“Yes it is!” he exclaims. “Gurtum,” he suddenly says, and points to a black-and-white picture of a man clad in a costume beset with an ornate hat and several banners protruding from his shoulders. A man who danced the dance of demons on Haslund’s journey.

The gurtum was a feared shamanic dancer that took part in festivals all over the steppes. At the festivals — including the important Maidari festival, which is the festival of the Maitreya bodhisattva — lamas would dress as gods and spirits, and in the end, the real crowd pleaser would emerge: the howling gurtum, considered a living god, swinging its weapons and striking fear in the hearts of the audience.

That is the name the young lama repeats to me now. “Gurtum.” He looks at me. “We still have this costume here at the temple.”

My eyes go wide.

We cross the temple yard. The earth beneath the temple grounds has been exhumed to lay cables and sewage pipes beneath the cobblestones and bricks, so the yard where the ritual dance once took place is in complete disarray. We walk on wooden planks over the holes in the ground, past a red and white board reading “How to decipher religious work regulations,” before we reach a building at the southern end of the temple.

The lama unlocks heavy wooden doors and we enter the dimly lit chamber.

“Gurtum,” he says, and points to the corner of the room. “This is where we keep the dress for the dance” — a dance that was banned after 1949, when it was branded as feudal superstition.

My eyes are adjusting from the autumn sun to the darkness of the room and I can’t make out what he’s pointing at. I step closer.

In the corner, the dress of the gurtum is draped from a hanger on the wall. The costume looks new and could not have been the one from 1927, but it is indeed similar to the picture in Haslund’s book.

“No photos please,” the lama says. “This is our hutuktu’s holiest dress.”

In the land of the Mongols, a hutuktu was regarded by many as representing the highest divine incarnation. Different temples hosted reincarnations of Buddha who were held as spiritual leaders, like the Panchen and Dalai Lamas. The hutuktu in Bailingmiao was one of the holiest on the steppes. The one that Haslund met — and documented in his book — was known as Yolros. (Another holy incarnation was Bogdo Gegen, the lamaist Buddhist leader in Ulaanbaatar.)

Next to the costume there’s a cropped version of the black-and-white picture from Haslund’s book.

“This is the head lama’s paternal grandfather,” he says.

“So your head lama is a direct descendant of the hutuktu?” I ask.

“He is the one who danced the demon’s dance in that picture.”

Considering Haslund suggested that the gurtum might kill participants in the ritual who were unfortunate enough to meet the wrath of the god incarnate, maybe it wouldn’t be a crowd-pleaser at a temple fair, I think to myself.

“But you do dance sometimes?” I ask.

“We can do it when nobody else is around.”

The young lamas fill copper cups with yak butter and invite me to help them prepare the candles that burn in the hundreds in front of the shrines throughout the temple. I learn that the young lama who showed me the gurtum dress is called Bai, and studied at the Lama Temple (雍和宫 Yōnghégōng) in Beijing.

“I don’t know much about the history of our Bailingmiao,” he says while filling a candle with a yellow and musky substance. “I know that our temple was damaged when the Japanese attacked. Later, the monks were driven away and it was used to house tractors and farming equipment. Then there was a school in the temple hall for a while, before the temple opened up again. That’s about it.”

And then, out of nowhere, in comes the head lama, possible descendant of the gurtum in Haslund’s book. He is a bit shorter than the other monks and speaks in a language that I cannot understand — a Tibetan dialect, the young lamas later tell me. He looks at me for a while with a piercing gaze, trying to make out the situation and probably asking himself why a foreigner is standing in his steppe temple. I have been caught up in the exhilaration of stumbling upon this place, and now I realize that out here, books like the one in my hand carry the power to set stories straight and create new ones.

“We were strangers here and acknowledged gods who were unknown on the steppes and the sight of us might call forth the infuriated gurtum’s lust for vengeance,” Haslund recounted when in the presence of the hutuktu.

I show the head lama the book, and he points to several of the pictures, speaking Tibetan in a low voice to Bai before looking at me.

“Really extraordinary. He says it is a very interesting book,” the young lama translates.

Bai then points at a caption. “What does it say here?”

“Yolros lama,” I tell him.

“Then that must be his grandfather. He says he has seen some of the pictures before, but not this book.”

The questions are beginning to pile up in my mind. Could he really be the grandson of the hutuktu in the pictures, like he claims? Maybe the head lama knows about the text, but has he kept it to himself?

He nods and smiles slightly, then abruptly turns and leaves the temple hall.

“It is truly yuanfen 缘分,” the young lama says and smiles, using the word for “fate” or “destiny.”

“I hope I have not disrespected your head lama,” I tell Bai.

“You haven’t, but we don’t know so much about that time. Us younger monks are very interested in history. When you go back to Beijing, be sure to contact my friend at the Lama Temple.”

The temples that operate on the steppes are in close contact with the Lama Temple in Beijing, which is one of the most important lamaist Buddhist temples outside Tibet. The clergy mix from prominent institutions across northern China, so it is not uncommon to find lamas who have lived in Hohhot, Beijing, as well as small obscure temples from Inner Mongolia to Manchuria. Bailingmiao is still trying to recruit more lamas and build up the temple clergy to its glory days, before the Second World War.

The head lama stands in the door. I nod to him as I leave and he nods back.

“The holiness of a hutuktu is the result of many earlier existences,” Haslund notes about Yolros, “and he is therefore a being of superior nature, highly exalted above the multitude.”

There are still mysteries to be found on the steppes, and unraveling them is a dance around history. For me it is an adventure, but for the lamas at Bailingmiao, it is part of an ongoing story of their temple. “To show this veneration to a hutuktu confers upon pilgrims renewed strength to endure their troubles and confirms their hope of one day reaching the right goal,” Haslund writes, referring to the pilgrims who pay their respects.

After I arrive back to Beijing, I stumble upon a Chinese version of Men and Gods in Mongolia from 2013. I buy a copy and mail it to Bailingmiao.

Bai’s reply comes a week later: “My friend, as a representative of the grasslands of Inner Mongolia, I would like to thank you deeply for returning this document.”