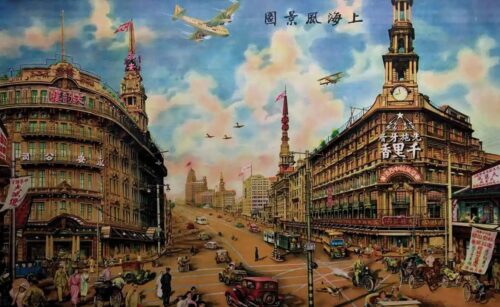

Prada takes over a grocery store in Shanghai

A wet market in Shanghai is co-opted to help a luxury brand sell clothes. Has internet celebrity culture — China’s “wanghong” economy — gone too far?

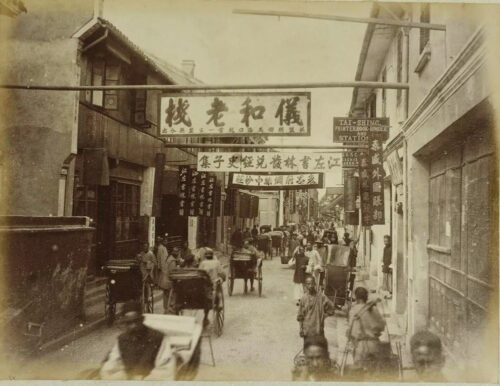

When you’ve lived in Shanghai for a while, you learn to keep away from the “hotspots,” what Chinese call wǎnghóng diàn 网红店 (“internet celebrity stores,” i.e., establishments made popular by key opinion leaders [KOLs]). On the inevitable occasion you encounter one, it feels like entering a photoshoot in a Black Mirror episode: surrounded by photographers, only the cameras are all pointed at themselves.

Last Friday, I got a glimpse of dystopia just a block from my home. The local wet market near my apartment was the site of a new campaign hosted by the iconic Italian fashion house Prada. I noticed the change a week earlier when the unassuming dark green storefront of the market was replaced with pink plaster and a humongous Prada logo. The lurid colors were a stark contrast from the surrounding scene, the ordinary tints and scents of steamed buns, soybean milk, and fried dough sticks. As expected, a cavalcade of established and aspiring influencers — the engines of the wanghong economy — flocked to the scene, turning my routine grocery run into a protracted obstacle relay.

The two-week ordeal is part of “Feels Like Prada,” a publicity campaign for the brand’s new fall/winter clothing line. The grocery store heist is, reportedly, part of the fashion house’s desire to partner with local retailers for a more “authentic experience.” Though this particular Shanghai wet market setup is temporary, the Italian brand is known for its ventures into food. In 2015, it bought a pastry shop in its home city of Milan, and it has since expanded into bakeries and coffee. If all goes to plan, big cities like Tokyo, London, Rome, and Paris will soon have Prada-branded pastries, coffee, and maybe even vegetables.

“We didn’t have a choice — it was management’s decision,” my regular grocer, in his late-30s, shouted at me as I made my way into the crowded market. He seemed relieved to see a familiar face. A sea of slender young women posing next to ripe tomatoes and eggplants stood, like a row of mannequins, between us. As I was checking out, l noticed that all my groceries now came with a gaudy black-and-pink wrap. Prices (luckily) hadn’t changed. “It’ll be over on the 10th,” he assured me, “and good riddance cause none of these people actually cook.”

Even in Shanghai, where residents have grown accustomed to the power of developers, big-budget marketers, and their seemingly unlimited license to rearrange urban spaces, Prada’s stunt drew both shock and intrigue. “Shit, even grocery stores can be wanghong spots now?” said an incredulous onlooker. “This is the closest I’ve ever gotten to being able to afford luxury goods,” wrote a cheeky blogger. For Prada, that was exactly the point. In 2015, when asked about Prada’s new foray into food, head designer Miuccia Prada told the Guardian, “I wanted to make culture attractive to the young [so that they would see] that it is necessary to your life…Art is for everybody and not a matter of private ownership.”

The Shanghai market co-optation, in Prada’s view, is part of a mission to democratize culture. At no point did Prada’s team consider whether the market, a 35-year-old gem in the French Concession, truly needed a face-lift in “culture.” Prada touted the event as “an unprecedented invitation to experience the emotional scope of the brand.” But tagging groceries with the brand of a multinational conglomerate is not likely to cleanse Ms. Prada of her association with “private ownership.”

The great Czech dissident Vaclav Havel, in 1982, asked his readers to consider why a greengrocer, in Communist Czechoslovakia, would put up a socialist slogan (“Workers of the World Unite!”) on his windowsill. China has had no shortage of similar slogans during this year’s National Day holiday week, but what of the greengrocer who asks if you want your Prada bag in paper or plastic? The answer seems simple enough: the grocer’s manager, in raising the profile of the store, was hoping to make a profit. China is a country of extremes, and it is no longer a novelty — to say nothing of a contradiction — to see a store owner hanging a Communist flag next to a Prada banner on a shopfront.

To understand why the Czech grocer decided, out of survivalist instinct, to display the socialist slogan, Havel looked to the underlying structure of power. Similarly, then, the Shanghai greengrocer’s willingness to give Prada the keys to his modest shop, out of a sort of commercial instinct, can’t be separated from the new structure that is China’s wanghong economy. In the past few years, all of China’s most successful consumer brands — such as HEYTEA, Genki Forest, Perfect Diary, and Chicecream — rose to fame in the wanghong system and its smorgasbord of livestreamers, KOLs, and social media. Millennial and GenZ Chinese, its primary movers and shakers, are a rising consumer segment of over 530 million people. They may not yet be able to afford Prada handbags, but they can certainly afford Prada groceries and pastries. It makes sense, then, for global brands to follow Prada’s lead.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

In the U.S., the army of influencers on YouTube and TikTok still seem largely divorced from the mainstream, offline economy. By contrast, China’s wanghong — on platforms like Douyin (which spawned TikTok), Little Red Book, and WeChat — are so intertwined with the physical marketplace that it’s hard to tell where one begins and the other ends.

New businesses now rely on influencers to drive traffic to their stores; other influencers rely on those same stores to drive traffic to their accounts; influencers who have amassed enough followers then get tapped by new businesses — and the cycle repeats. This endless feedback loop between the physical and digital worlds constitutes the nuts and bolts of the wanghong economy. Its operating force, what propels it into motion, is that same quirk of psychology responsible for speculative bubbles, what the 19th-century historian of finance Charles MacKay called “the madness of crowds.” It’s hard to overstate the power behind this mechanism: If China’s internet, with respect to politics, evolved to manage the flow of ideas, its consumer internet has evolved to direct the flow of bodies.

Perhaps someday I’ll look back at that time Prada descended upon my local market as signifying a tipping point, when the digital world of rankings, followers, likes, and algorithms gained the upper edge over the physical world of grocery stores, cafes, and bakeries. At that moment, events in real life began to presuppose events in virtual life; the principal reason to inhabit a space was no longer to do something, but to get noticed doing it; arrangements in the physical world began to depend on the exigencies of vanity rather than functionality. At that moment, people’s relationship with their surroundings changed irrevocably.

But not today. Today, I’ll be staying home, and far away from social media.