This Week in China’s History: October 9, 1740

Fittingly, the events in this column usually take place in China. There have been a few exceptions, usually to do with anti-Chinese violence in the United States. This week, another new destination, though sadly still one with violence at its core.

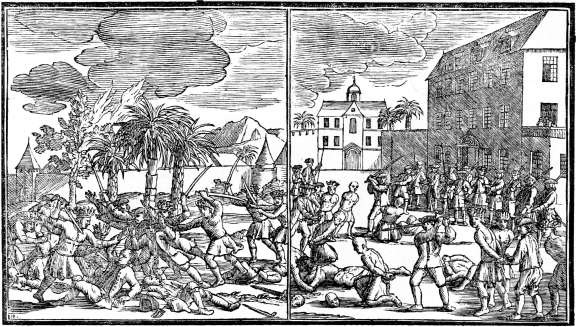

This went on for nearly two weeks. By the time the violence ended — paused might be a better word — 10,000 Chinese had died in and around the colonial capital.

The overwhelming majority of victims were Chinese, but the violence was widespread. Battles between Chinese and colonial authorities, and between Chinese and the indigenous populations, spread across the region. Several hundred Dutch or indigenous people were killed when the Chinese fought back.

As appalling as this loss of life was, it was even more shocking given the history of the region and often productive relations between the many groups living there. How had it turned to an orgy of violence?

And there is another question too: why would one important historian refer to Batavia as “a Chinese colonial town”? The layers of power, and the interactions of empire, are woven deeply through the fabric of Java, and understanding the events of October 1740 requires approaching them from many different directions. Historian Prasenjit Duara, in the title of a provocative book, challenges us to “rescue history from the nation,” and Southeast Asia’s contested and diverse land and seascapes challenge us to do just that: any single national history — whether Chinese, Indonesian, Malaysian, Dutch, or any other — will only give part of the story.

The Chinese diaspora is getting increasing attention recently. Mae Ngai’s important The Chinese Question is just one example, and in the United States, the history of anti-Chinese violence has been remembered — including in this column about the Rock Springs massacre, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and the “coolie” trade — in the context of different racial reckonings. But these have focused mainly on the diaspora in the Americas. Historian Eric Tagliacozzo notes the importance of Southeast Asia for analyzing this movement. In his conclusion to a collection of essays, Chinese Circulations, he writes, “Though Chinese did indeed end up in places as far afield as [Chicago and Peru], it is clear that the locus classicus for both Chinese emigration and Chinese commercial expansion during this period was the Nanyang, or “South Seas” (Southeast Asia). This is…true on the whole for most fields of business and endeavor, as the numbers of Chinese who eventually left for these places attest to over many years.”

Illustrating Tagliacozzo’s point, as many as 15,000 Chinese lived in and around Batavia, many of them connected with the sugar industry, by the middle of the 18th century. Their presence wasn’t new. Long before the nine-dashed lines and the island-building claims of the People’s Republic, a diaspora of Chinese from all walks of life — merchants, laborers, monks, travelers — spread across the warm shallow waters. What we today designate as Southeast Asia is, and was, a pivot; an intersection among a dozen different worlds from mainland and maritime Southeast Asia, and farther afield.

Ironically, and for historians frustratingly, maritime connections between southern China and Southeast Asia appear to have been so commonplace, since at least the Song dynasty, that activity was often taken for granted, thereby leaving few records. Historian Leonard Blussé has tried to reconstruct the movements and trade across the sea: “Propelled by the northeastern monsoon, year after year Chinese junks carried tens of thousands of people abroad, thereby creating pockets of Chinese settlement all around the rim of the South China Sea.”

Batavia — the Dutch colony on the island of Java in what is today Indonesia — had been a central destination for many Chinese. The Dutch formally established their settlement in the early 17th century, naming it after the supposed ancestors of the Dutch people. The surrounding region became important for sugar cultivation, controlled almost entirely by Chinese. In 1710, historian Blussé has found, 130 sugar mills were owned by 84 people. Of those 84, 79 were Chinese, 4 Dutch, and one Javanese.

The Chinese and Dutch in Java co-existed as long as the sugar economy thrived. But as sugar cultivation expanded in other parts of the world — the British and French Caribbean, for example — global prices fell. The decline hit the Javan sugar industry hard, leaving many of the Chinese arrivals in Batavia without work. The Dutch colonial government began deporting these (usually undocumented) Chinese, often to their other colonies in Ceylon or South Africa. Rumors spread that the deported Chinese were not being relocated, but dumped overboard to drown at sea. As Chinese organized resistance, anti-Chinese riots began to break out among the Dutch settlers and other ethnic communities. In this context, the mass murder seems a grim but familiar story, one we have seen repeated in the United States, but which had counterparts in Southeast Asia: economic disruption, scapegoating, and then violence.

Blussé, though, argues that there is something more going on, no less violent or tragic, but less straightforward.

The colonial nature of Batavia was layered. Dutch settlers were at the top, but the Chinese were not at the bottom. Acknowledging their vital role in the colony’s sugar-based economy, Chinese were allowed to reside inside the city walls of Batavia. The local Javanese were not. Besides the traders who lived in the city, laborers arriving regularly from China lived mostly in the surrounding region. By the 18th century, as Blussé has described, “the city of Batavia was, notwithstanding the misleading image given by its canals and brick gables, economically speaking, basically a Chinese colonial town under Dutch protection,” with the castle serving as the center of an imperial Dutch network of trading posts, and the town playing the same role for a Chinese trade network.

The two parallel commercial networks thrived into the 18th century. At that point, though, both sides tried to expand their commercial networks at the expense of one another. Critically, the Dutch revision of the arrangement undermined the authority of the Chinese community’s leader, Ni Hoe-kong. Unable to manage the relationship with the Dutch to his people’s advantage, Ni lost influence. When the Dutch began deporting large numbers of Chinese laborers, and with Ni helpless to stop it, the laboring Chinese population of the island rebelled — against the perceived misrule of Ni Hoe-kong as much as the oppression of the Dutch.

For decades, the Dutch — principally the VOC — had been trying to deport and exclude the Chinese in order to keep more of Batavia’s profits for themselves. Instead, they found a faster, bloodier solution to their “Chinese problem.” Fear, racism, and cynical political calculation mobilized the Dutch soldiers, colonists, and the local Javanese, who turned on the community they had been living alongside for generations and purged them in blood. Ironically, the people who suffered the most were the Chinese who lived inside the city and were both physically and economically closest to the Dutch. Murdered because of their race, they were the least likely to have taken up arms against either the local Chinese leadership or the Dutch.

Despite the bloodshed, Java remained an important port of call for the Chinese junk trade in the South China Sea. Within a decade of the massacre, more than 50 junks were arriving each year at Batavia, from Ningbo, Guangzhou, and Xiamen primarily.

Beyond its local importance, and the horror of the people killed, the Chinese massacre illustrates the global nature of history. Seen through a strictly Chinese, Dutch, or Javanese lens, the events of 1740 appear in just one context, but when the scope is widened to incorporate multiple perspectives, the complexity of what happened emerges.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.