Taiwan’s education soft power push

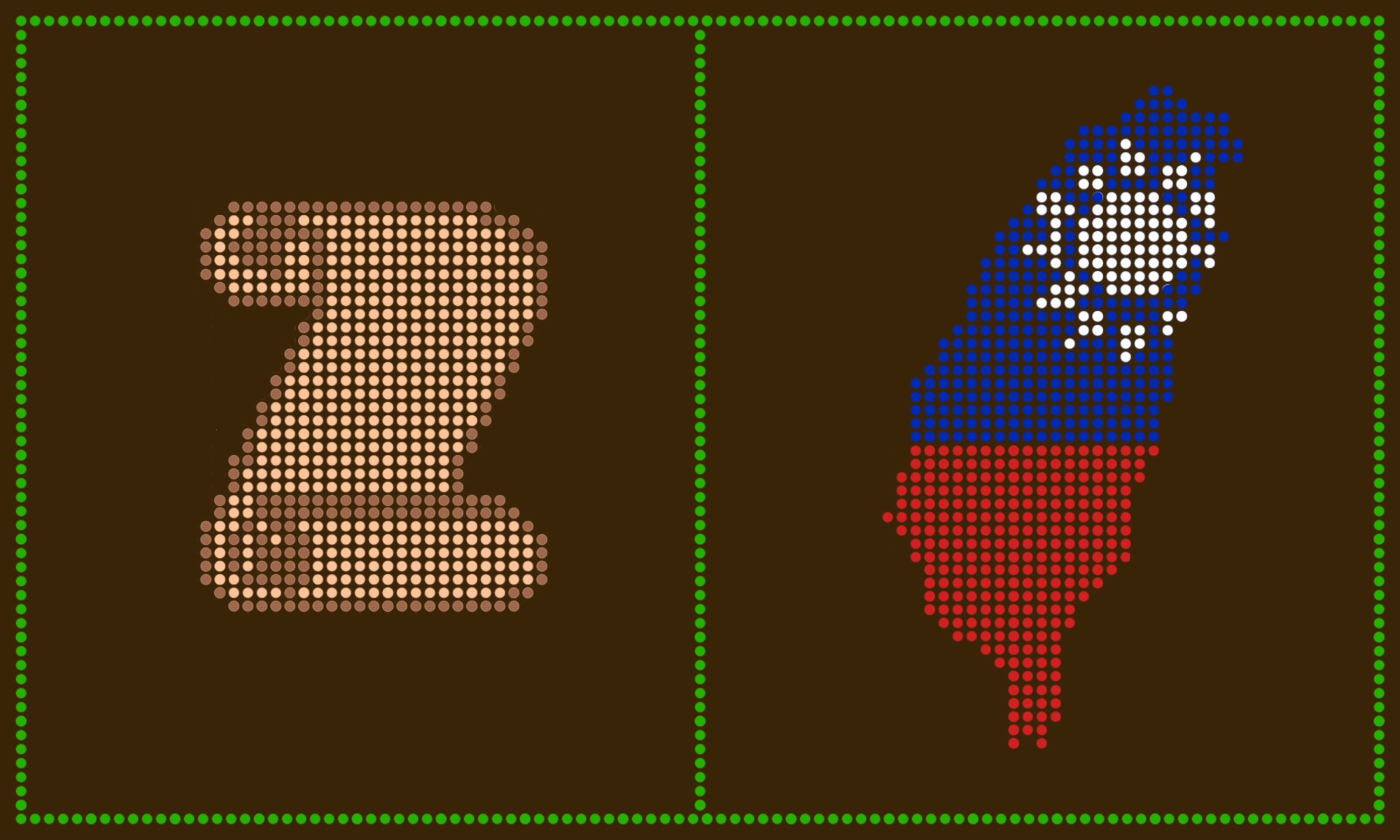

Taiwan has been beefing up its international education campaign, but experts say it will be difficult to compete with China.

When news broke in October of Harvard’s relocation of its Chinese language program from Beijing to Taipei, it reminded many of the days when Taiwan was the world’s premier center for Mandarin learning — some 30 years ago, when mainland China was still acclimating to the international community. Harvard cited growing operational difficulties with its partner school, Beijing Language and Culture University, and cooling attitudes toward Americans as its reasons behind the move.

Today, with China remaining closed to students due to its strict COVID-19 protocols, other study abroad programs, language exchanges, and individual students have shifted their focus to the other side of the strait.

Taiwan has rapidly expanded its soft power initiatives through both Mandarin and English programs, targeted at bringing people to the island and expanding into the China-dominated Mandarin education market abroad. Paired with the goal of becoming a bilingual society by 2030, Taiwan wants the world to see it as “Western, yet influenced by a Chinese civilization and shaped by Asian traditions,” as President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén) has herself put it.

“Taiwan in the last two to three years has established itself as a clear opposition to China,” says Stefano Pelaggi, a research fellow at the Taiwan Center for International Strategic Studies. “Not ‘free China,’ not the ‘real China,’ but with a clear line as a democratic country with free speech and so on.”

The American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) — the de facto U.S. embassy — has recently put forward its U.S.-Taiwan Education Initiative. It has partnered with universities like UCLA and the University of St. Thomas in Houston, Texas to “expand access to Mandarin and English learning” through teacher exchanges “while safeguarding academic freedom,” according to AIT.

The time is ripe. Tolerance for Confucius Institutes has dwindled, leading to mass closures and leaving only 36 in the U.S. as of last month (a number expected to continue to go down before year’s end).

In September, Taiwan’s Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC) announced new Taiwan Centers for Mandarin Learning (TCMLs), which will lend funding, resources, and training to compatriot schools in the United States and Europe. So far, 18 have been approved, and according to reporting from Politico, OCAC aims to open a total of 100 within the next three to five years.

The centers will not only focus on Mandarin teaching, but should also “tell the story of Taiwan to U.S. students who are learning Chinese more fully,” reads an OCAC document describing the initiative. That will include cultural and international exchanges that emphasize the use of traditional Chinese characters and Taiwan’s democratic society.

“These kinds of political issues opened a door for Taiwan, for Taiwanese teachers to go abroad,” said Kevvy Yang, an English teaching advisor with Fulbright Taiwan. “In the past, I also wanted to be a Chinese teacher, teaching abroad. But China kind of occupied the whole market, so I didn’t really think it was a very long-term thing that I could do. But now things are changing, because people don’t really trust China.”

Taiwan’s goal of becoming a bilingual society by 2030 to boost national competitiveness has also led to a record number of English Teaching Assistants there under the Fulbright program, with over 200 teachers this year, making it the largest Fulbright ETA program in the world. Also, the number of Taiwanese Mandarin teaching assistants in the U.S. under Fulbright has more than doubled in the past five years, with 45 Fulbright Mandarin teachers in the U.S. today.

“All languages and cultures are politically laden, and geopolitical tensions tend to make it more explicit,” says Jing Qi, a lecturer at RMIT University in Melbourne who has written about China’s strategy to become a leading host of international students. “In times of geopolitical turbulence, countries and regions tend to think about languages more in terms of their political and diplomatic impacts, in addition to the economic and trade benefits of multilingualism.”

Language, particularly English, has long been used as a tool of influence and soft power abroad. But China’s recent policy that restricts private English tutoring online indicates a growing focus on “localized” English training to minimize Western political influences.

That doesn’t mean China has turned its back on the significance of English for global engagement, Qi says. “China will continue to use and teach English as a pragmatic solution to global participation. The difference will be in further instrumentalizing English for national branding,” he says. “China has a strong capacity to teach English on their own terms because of four decades of work in English language education and English language teacher training.”

Despite the millions that Taiwan is investing in English-taught degree programs to attract international students and Mandarin centers abroad, China remains a dominant force that may be impossible to overtake, even given its declining global reputation.

“I am not sure how much of a gap [left by Confucius Institutes] there exists to be filled,” Qi says. Mandarin speakers across the world, such as American, Australian, and European citizens of Chinese heritage, have been teaching Mandarin at schools, universities, and in their communities. In addition, transnational online education like China’s own Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have made language learning resources accessible to global learners for free.

For Taiwan to be successful, says Tsang from SOAS, it will have to be more than just an answer to Confucius Institutes, which means developing new teaching methods and staying away from politics.

“If you try to teach a language with a political message embedded in it, then you are getting people to wonder whether you are the best language teacher. That will push people away,” Tsang says. “The imperative is therefore for [Taiwan] not to squander it, and make people think they are just like China.”