Xinjiang: On technology and crimes against humanity

The camp system in Xinjiang — the largest internment of a religious minority since World War II — is the first to employ a comprehensive digital surveillance system across an entire population, a "super panoptic" that uses automated, real-time assessments of massive amounts of data to sort populations based on their racial phenotypes and digital records.

In her famous attempt to define what constitutes crimes against humanity, Hannah Arendt argues that the inability to think, the banal normalization of bureaucratic rules and accounting, is what enables the systematic unjust internment of ethnic and religious minorities. She insisted that the term “thinking” does not refer to simply making the conscious choice to follow orders, but rather that it means being able to step back and understand the implications of actions that dehumanize others. Thinking means being aware of history and the way the present rhymes with it.

Arendt was attempting to understand how the exceptional crimes of the Holocaust were normalized. Like Primo Levi, another lucid interpreter of those events, she recognized that the camp machine required obedient functionaries: guards, cooks, cleaners, doctors, accountants, and many more. The threat of arbitrary detention and death enacted by surveillance and informants is what impeded thought in this context.

As I was writing In the Camps, a book that examines a new camp system — the Uyghur, Kazakh, and Hui re-education camps in Northwest China — I came back to Arendt and Levi again and again. They helped me understand the continuities and differences of life in camp systems over time.

At times it appeared as though the “never again” of Holocaust survival was on the minds of detainees and functionaries in Xinjiang. A brave University of Washington international student named Vera Zhou, who was detained when she went home to visit her family in 2017, told the other Muslim women in her cell the story of Anne Frank, which she had read in high school in Oregon. In the back of a city bus on the outskirts of Urumqi, a Han camp worker told his Uyghur colleague, “How can this be happening now? Isn’t this the 21st century?”

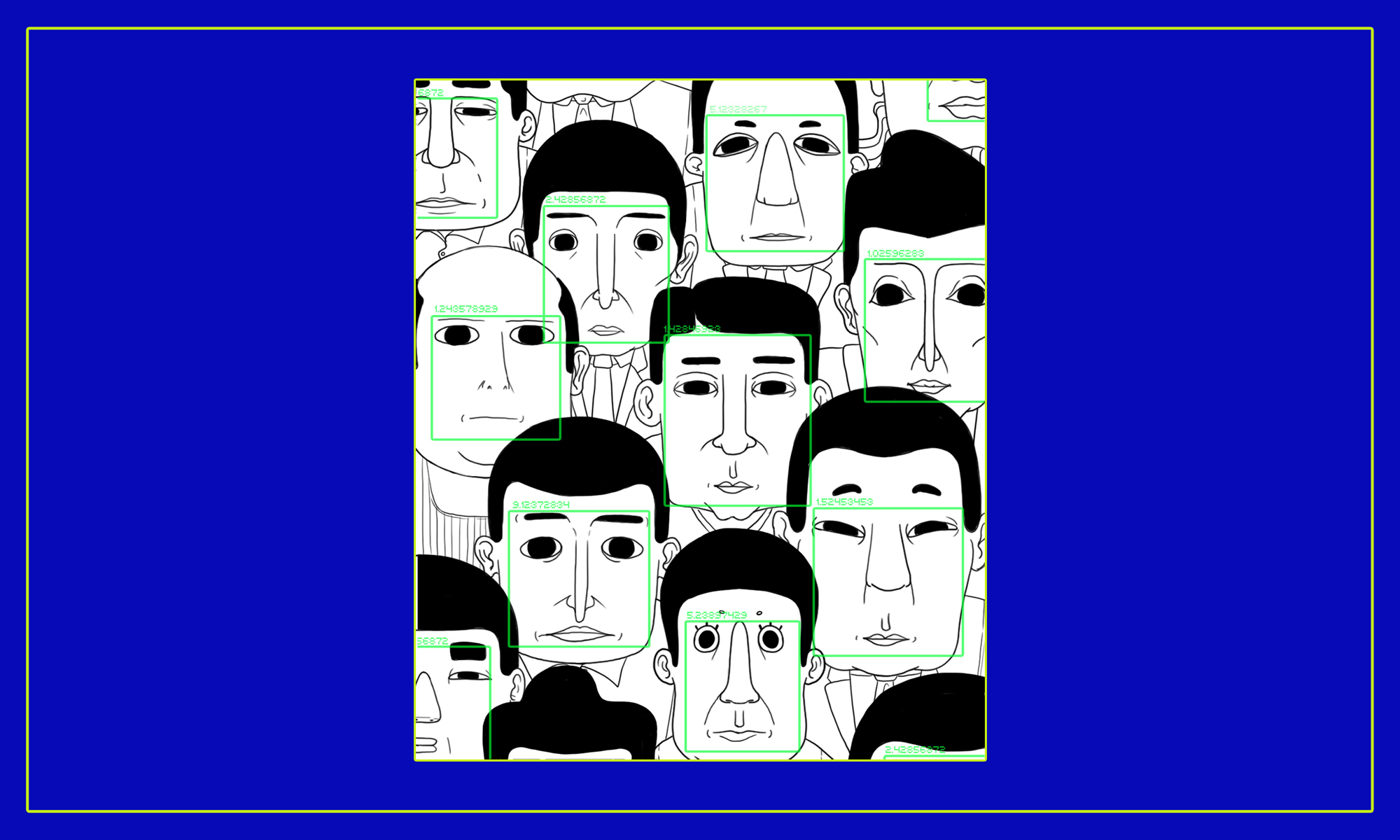

But while the presence of reflective thinking is worth noting in and of itself, there is an important difference between it and its absence — aside from the occasional Schindler — in atrocities past. In contemporary Northwest China, reflective thinking happens in narrow spaces and urgent whispers outside the gaze of cameras and the range of microphones. The system in Xinjiang — the largest internment of a religious minority since World War II — is the first to employ a comprehensive digital surveillance system across an entire population.

Not only does it employ police towers, walls, checkpoints, barbed wire, machine guns, and even the surveillance cameras of past camp systems, but it also uses the advanced technologies of facial recognition and digital history searches. The system is what the theorist Mark Poster refers to as “super panoptic” — meaning that it uses automated, real-time assessments of massive amounts of data to sort populations based on their racial phenotypes and digital records.

When the mass detentions were implemented under the direction of the Xi Jinping administration in 2017, the detainees were first held in crowded police offices, decommissioned office buildings, warehouses, and nursing homes. Over time, many of these existing buildings and newly constructed detention facilities were outfitted with sophisticated cameras, sound detection equipment, and command centers with banks of screens. Bright lights were never turned off. Detainees were forced to sit ramrod straight on plastic stools and listen to speeches and language instruction on flat-screen televisions mounted on the walls. At night they were not permitted to cover their faces with their hands. Violating any of these rules often resulted in warnings issued over an intercom system. In some cases the cameras were motion-activated and face-recognition-enabled. The guards and camp workers also did their work in front of the cameras wired for sound. Everything was recorded, available for algorithmic assessment in real time.

The detainees were guilty, Chinese authorities would tell the U.N., of “terrorism and extremism crimes that were not serious” or “did not cause actual harm.” Internal police documents show that in many cases they were deemed untrustworthy due to past digital activity. Being part of WeChat groups where participants discussed Islamic practice or how to read the Quran was one of the most frequent “extremism crimes.” More than 100,000 individuals were tagged as potentially “untrustworthy” for these types of cyber crimes alone.

Outside of the camps, the threat of being deemed untrustworthy prevented people from attending mosques or celebrating Islamic holy days associated with Ramadan. At the entrances of mosques, face recognition checkpoints counted Muslim attendance. Regular scans of smartphones with plug-in digital forensics tools called “counter-terrorism swords” examined past digital behavior for probable matches with as many as 73,000 markers of illegal religious and political behavior.

In addition to the tens of thousands of guards Public Security Bureaus hired for the rapidly expanding camps and prisons, the government hired more than 60,000 entry-level police officers, assistants, and militia to act as “grid workers,” waving non-Muslims through checkpoints, scanning Muslim phones and faces, and inspecting the homes of suspects and their family members. As in camp systems past, swarms of low-level functionaries ensured the function of the system. But their orientation was not just toward those in authority above, but rather to the platforms they held in their hands. The Xinjiang camps were the first to be managed by smartphone.

The algorithms that produce the population of extremists and terrorists whose crimes are “not serious” normalizes cruelty in a way that Arendt could not fully predict. First, technologies which control movement and thinking in such total and automated ways seem to preclude the intentional mass killing that accompanied past genocidal moments. In Xinjiang they are being used to justify the removal of more than half a million children from their homes, placing hundreds of thousands of parents in factories, but they also make people continue to live. As a region-wide camp manual put it, “abnormal deaths are not permitted.”

Second, such systems appear to wear down populations, changing the way they behave and work, and over time, they change how people think. The former detainees I interviewed spoke about how their social networks were transformed, how friends turned each other in, how they stopped using their phones for anything other than promoting state ideology because of the checkpoints. They adapted to the new reality.

Third, advanced technologies mask their evaluative processes, producing a blackbox effect. Unlike Eichmann’s ledgers and Nazi protocols, the tens of thousands of micro-clues that go into a diagnosis of an untrustworthy Uyghur are often too complex to play out through the reflective rationality that Arendt described as “thinking.” A “smart” internment system produces an automated crime against humanity, which means that moral judgments of it must be expanded beyond functionaries and political leaders to software designers who may be many steps removed from the application of the technology.

Aspects of the technologies used in the system are rooted in global technology developments. A culture of rapid prototyping and open-source knowledge dissemination, of an industry dominated by big tech, has provided the infrastructures that gave this system its start. The backend of the policing and mass internment system I analyzed was built in part using open-source Oracle products; early in their development, the face recognition companies were assisted by a University of Washington dataset and training from Microsoft Research Asia, and one of the digital forensics companies partnered with MIT.

The cries of “never again” that are echoing through the Uyghur and Kazakh communities in which people have escaped demand a rethinking of surveillance technology from the perspective of the most vulnerable. Crimes against humanity that are born digital can be leaked, assessed, and decried more quickly than past mass internment systems, but when the technologies that undergird such systems are out in the world, it is hard to stop them from being adapted in new locations. Perhaps the best we can do now is design technologies that expose injustice and protect those who are most vulnerable.